Samuel, age five, came to Mother one day and asked if they could pray for a little sister for him. Mother said, “All right,” but she did not immediately follow through because she had already been praying earnestly for some time. She thought that perhaps it was not God’s will to give her another child and she did not want to beg.

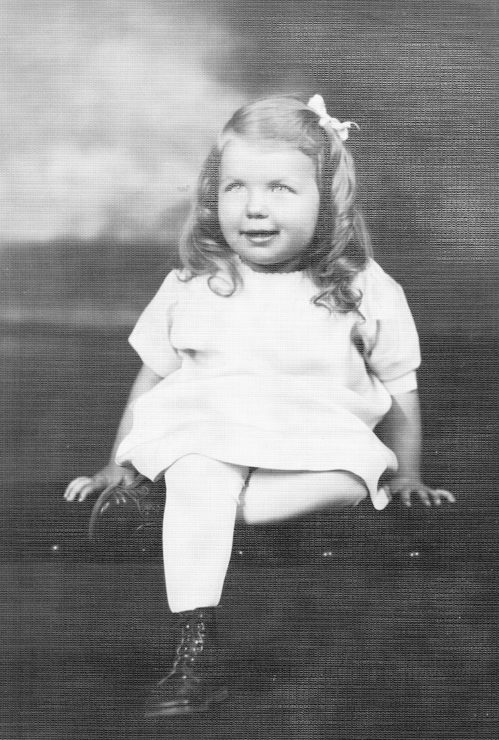

“I mean right now,” Samuel urged. When Mother began to kneel, he insisted that Father join them, so the three knelt together and prayed. About ten months later, on October 7, 1932, I was born, Grace Susanna Herr. Could it be that because I came into this world on the power of prayer, it became the fervent centerpiece of my life?

My mother told the story of how I came to Christ at a young age. She wrote in my baby book that one evening after altar service in a tent meeting she said quietly to me, “You want to be a Christian sometime too, don’t you?” And, with something of wonder in my “earnest baby face,” I said, “I’m a Christian now, aren’t I?” Then in June 1937 the entry reads, “In a children’s meeting at [General] Conference Grace and another little boy went out to the altar to get saved. They said she was so sweet about it. I was not with her but I know she is a very earnest little pray-er.”

Father was eager to be a faithful servant and raise a godly family. Over the eating area in our big kitchen, he mounted a large wooden arch with a carefully cut-out motto that quoted Joshua 24:15, “As for me and my house we will serve the Lord.” I was told that it took him many hours to cut it out by hand with a coping saw. Today that arch is in my home—in fact you might say that my apartment was designed around it.

When I was born, the family had just moved into the new house built by my father on part of the land purchased by his great grandfather, near the settlement of Dayton, Ohio, on the Stillwater River. My father, Ohmer Ulery Herr, had heard stories about this purchase when he was a boy. In 1832 his great grandfather, Samuel Herr, bought some 400 acres reaching west from the river and moved there when his son, Samuel L. Herr was four years old. Ten years later Ohmer’s great grandfather took the boy, now 14, back to Lebanon County, Pennsylvania, to help bring a large herd of cattle to the farm in Ohio, since the cattle in the east were more plentiful and therefore cheaper. The drive was more than 500 miles long and took most of the summer. Ohmer’s grandfather, Samuel L., told him that during the trip they stayed at various way-houses overnight, and on one occasion they slept in a house where the ceiling of the sleeping loft was not high enough for a person to stand upright. During the night the young man began to dream and rose up quickly in his sleep to chase a cow back in line. When he did this, he gave himself a sharp blow to the head which he never forgot.

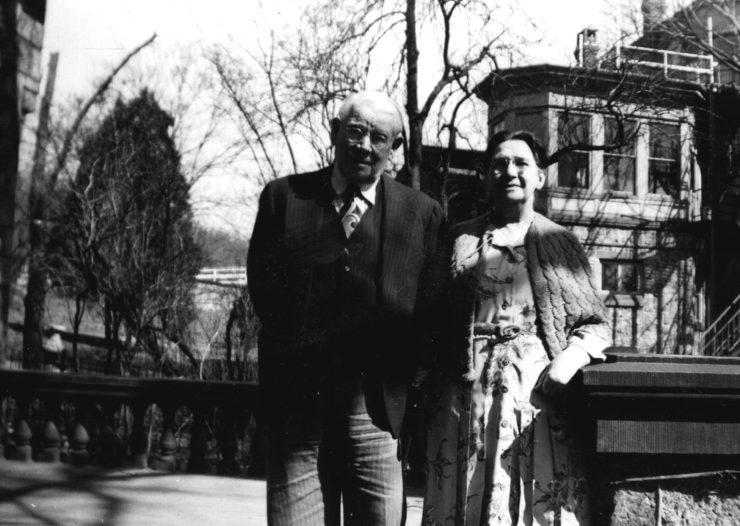

At the time of my birth, my father was pastor of the Fairview Brethren in Christ Church at Englewood, along with several other men who assisted. Ohmer and his younger brother Ralph were sons of Levi Herr, who apparently lived an influential life as a pastor himself, but died of cancer when my father was 15 years old. My Grandma Iva (Ulery) wrote and published a little book about Levi’s experience called Gleanings from the Christian Life of One Made Perfect in Love. My father and Grandma Herr carried on with the farm for some 20 years—one of the positions of responsibility that my father took seriously during his lifetime. Uncle Ralph became nearly blind from measles as a child and never married. He sometimes had spiritual struggles, but all his life he loved to sing hymns of praise.

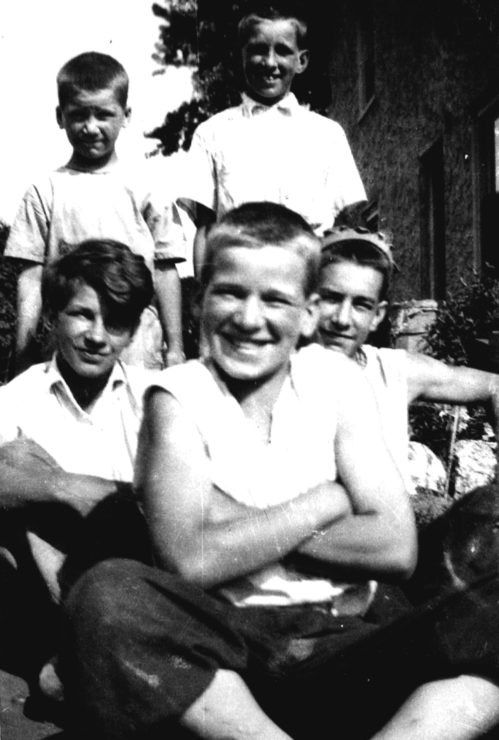

My mother, Anna Rozella, was the daughter of home missionaries, William and Suzie Boyer, who by the time I was born, had been serving for 20 years among the needy of the city of Dayton. My mother’s brother, Clarence, had a religious bookstore and typewriter repair business in the city and was extremely supportive of the mission. He and his wife Ethel (French), whom he met when she came to serve as a worker at the mission, had three sons—William, Ernest and Paul. We were surrounded by prayer, Bible study, and ministry. I was loved, cared for, and taught. When I was almost two, little sister Ruth was born and we traveled life together, sharing toys and celebrations. I don’t remember quarreling, although I don’t know if it was because of her cooperative nature or my strong control? Four and a half years later we welcomed a little brother, Paul. People said he had no hair but we sisters insisted that he was just so blond you couldn’t see it.

We will serve the Lord

In those days the Brethren in Christ were one of the “plain people” groups with emphasis on separation from the world in dress and lifestyle. It was not appropriate to call attention to oneself with “gold and pearls and costly array.” Hard work and frugality were greatly valued, and church attendance was regular and meaningful. Scripture was the authority, and we followed it as literally as we could. When I was in fourth grade, the congregation set about reading the Bible through in a year. I made it, and so did my little sister, Ruth. We managed not to wonder too much about the complicated events and issues we were reading. Nonresistance was taught as a powerful response to war and relational conflicts. During World War II, young men from our congregation went off to Civilian Public Service camps where, for a pittance provided by the church, they built roads or worked in mental hospitals instead of serving in the army. My parents, and the other members of the congregation, had a clear devotion to God. Their faith was genuine and it infused every area of life.

Missionaries often visited our church and stayed in our home. Our bookcase had a special section filled with interesting things from other parts of the world. Mother recorded that at age three I wanted to save some pieces of an orange “for the missionaries on the field.” Letters from missionaries were often read in prayer meeting, and children’s meetings included stories from overseas. We knew what it meant when we sang, “Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in his sight.” One Sunday night, missionary Effie Rohrer had a story time and told us about the children in India. I was touched, and remember thinking that maybe God would want me to be a missionary. I was about nine years old at the time. A few years later, I went forward at the end of a mission service to indicate that God was speaking to me.

We had a few cows and sheep, fed with hay and grain that we grew in two small fields remaining after the big farm was sold. Before the days of baling hay I sometimes helped to push the hay back in the mow and can still taste the pink lemonade that Grandma Herr brought to help us endure the punishing temperatures. She made it from her home-canned grape juice and put fresh lemon slices in it. Sometimes I got up early to roam the farm before work began and used the time to dig up blue and yellow violets, bloodroot, spring beauties, and jack-in-the-pulpits from our little woods. I planted them near the house so I could see them often. It seemed I couldn’t get enough of flowers. Grandpa Boyer conducted many funerals in the city, since he had an agreement with the undertakers that he would lead a service for anyone needing it. By the time of his death at age 99, he had conducted more than 1,300 funeral services, using each opportunity to offer the message of salvation. Whenever possible, Grandma Boyer delighted me with a few flowers saved from the funeral bouquets.

Sunday services at the mission were in the afternoon, so our family often attended to lend support. When I was in fifth or sixth grade they held their first Vacation Bible School and we children attended. I loved the flannel graph stories, the crafts, and the memory work. We had a contest to see who could memorize the most verses. My competitive spirit went to work as I memorized the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5, 6, and 7) during the two weeks.

Every other Sunday night was young people’s meeting at Fairview. The adults attended with us. Sometimes they spoke to us and sometimes we were assigned “topics” to speak about ourselves. We liked it when my mother spoke because she always illustrated her points—with a real bird’s nest, a broken dish, or a drawing of what we would look like without bones (likened to God’s laws). We learned to lead the a cappella singing and to sing parts. I remember once apologizing to people sitting near me for the way I slid around trying to find alto notes. At home we had a piano and we children received piano lessons from a member of the congregation, but at church we were only “singing and making melody in our hearts to the Lord.” Like other Brethren in Christ churches of that era, we did not have musical instruments. Eager to be liked by my peers like any other adolescent, I remember deciding that I could grow more attractive through appreciating others than by trying to get them to appreciate me.

Sanctification as a “second work of grace” was being taught in the denomination, and when I was 12, I sought such a work. I knew that I needed God’s deep cleansing and power in order to live a consistent Christian life. Some folks sought and received unusual experiences as they dealt with issues in their lives and felt the freedom of surrender. My father wisely taught that sanctification was a step of faith similar to being born again and that we could ask and receive the special filling of the Holy Spirit, even though the Spirit came in when we received Jesus into our hearts. Though there were times when I knew I was not totally obedient, I understood that I could come to God in repentance and be restored. We were led to confess the sin nature and give ourselves in consecration as an important step, but were taught that sanctification was also an ongoing process, and so I was spared the struggle of those who questioned their “experience” every time they stumbled.

Making melody

High school brought opportunities to sing. I sang solos in the school choir and in state competitions. I was blessed with peers from church who sang with my sister and me at school and at church. One year we sang at General Conference and later we became an official quartet at Messiah College. I enjoyed writing and was chosen to be editor of the high school yearbook. After graduation I was asked to edit the “Truth for Youth” page in the denominational Sunday School take-home paper. I worked hard at this assignment, planning themes, asking others to write, and composing articles myself.

My parents asked me to stay home for a year before entering college and I found a job as a secretary at the Humane Society in Dayton. There I got a glimpse of how some of the rest of the world lived. Though we had a bit of involvement with animals, our daily work back then consisted of accepting and issuing thousands of dollars of child support payments and sending warning letters to fathers who failed to make these payments. I’d had no idea there were so many hurting families in the world! Members of the office staff also demonstrated brokenness as they went through phases of refusing to talk to one another. I was relieved when I could give notice and get ready to attend college.

I loved studying at Messiah College in Grantham, Pennsylvania. I admired the dedicated faculty and took seriously their challenges to help students be careful thinkers. Even though there were only about 250 students in the high school and junior college in 1951, I made many new friends who were serious about serving God. I wanted to learn lots and took extra courses. I was still editing “Truth for Youth,” and I was in the Ladies’ Quartet, Ladies’ Chorus, Choral Society, and Oratorio Society. I played the piano to accompany voice students, earning a little money for expenses. I joined Gospel Team for off-campus ministry. For a breather, I enjoyed relaxing and worshipping in chapel and loved the Sunday afternoon nature hikes. The lichens and ferns we discovered in their alternating generations on the banks of the Minnemingo (as we called the Yellow Breeches Creek running through the campus) are etched in my memory. My resolve, kept throughout college, never to study on Sunday probably preserved my sanity. At Messiah I sometimes daydreamed about where life might take me. One day after hearing of the city of Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia, out of sudden curiosity I went to the world atlas in the library and looked up that country. Somehow I was filled with wonder to see the city there on the map as real as could be. I would have been infinitely more amazed had I known the part this city would play in much of my adult life!

During the first week of college, as my roommate and I were walking back from Keefer’s Store on the “square” in Grantham, a car pulled up beside us. My roommate, who had already spent a year at Messiah, introduced me to Fred Holland. Fred had a girl with him but asked if we wanted a ride. We accepted and climbed into the back seat. Instead of heading back to the college, Fred took a right over the Minnemingo and at quite a clip went through the little covered bridge that was next to the old mill house. The abrupt approach brought a pile of coat hangers from the back window to shower over us. It was an unusual introduction to my future husband.

Later, after we had spent a few casual times together, Fred invited me to dinner one evening at Howard Johnson’s on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. We had a very serious discussion. He told me some of his story and asked if I would help him by correcting his grammar and suggesting improvements in his behavior. I took the bait and no doubt became most annoying in my interventions. He gave me a little book, wrote notes to me, and gave me a picture of himself. Then one Friday night we were at an activity at a faculty member’s home where Fred goofed off the whole evening. I went back to my dorm room and put the book, notes, and picture in a paper bag and threw them to the back of the top shelf of my closet. Fred was not the kind of man I had in mind!

A different story

I couldn’t forget him, however. I was attracted to a man who seemed absolutely committed to serving God, as was I. Fred was concerned about lost people. He was headed for missions. He was generous and loved people. He had a sense of humor—and a story worthy of a motion picture.

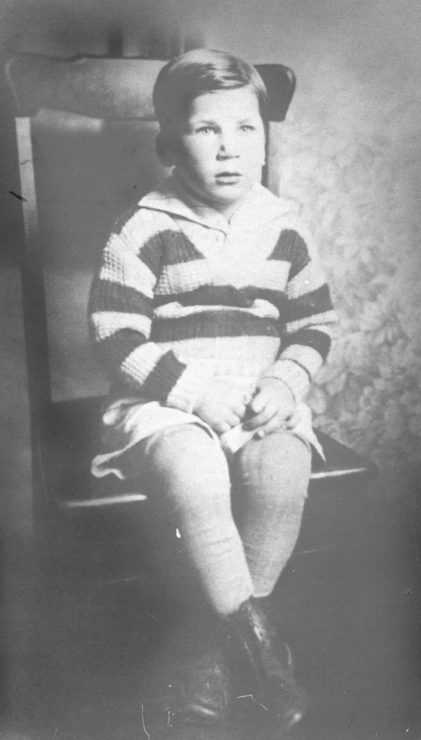

The story began with a tragedy. The father of Fred’s four older half-brothers had died in an accident. His motherad remarried and become pregnant with Fred, but the man left before Fred was born on March 10, 1926 in Philadelphia. He was told that his mother then left the five boys when he was about a year old, and his oldest brother Charlie put Fred (Buddy to the family) and the silverware in the baby carriage and led the brood to their maternal Grammy Hann’s house. There they slept in the unfinished cellar while the grandmother bootlegged upstairs for the boarders, who were Irish immigrants building the Philadelphia subway.

The boys grew. One day the older ones were sitting on the porch with a friend who had a gun and was pointing it at passing cars. Fred’s step-grandfather announced, “If we’re going to raise Sophia’s boys, we can’t do it in Philadelphia!” He rented a little farm for the family on a hill in Conshohocken while he commuted every day to work in the city, building displays and making repairs as a carpenter for Wanamaker’s, the famous department store. On the Saturday the family moved to the country, a lady in a long dress with long sleeves came up the hill and invited them to church. Grandpop Hann said, “Yep, that’s what we need!” So they trooped down the hill and began attending the Conshohocken Holiness Christian Church. Charlie was saved and began preaching at age 17. Fred made a start but got sidetracked. His uncles gave him alcohol. As a teenager he remembers bragging that he could hold his drink, drank too much, passed out on the steps of the city hall in Philadelphia and was taken to the hospital. When he came to, he retrieved his clothes from the locker beside his bed, climbed out the window, shinnied down the spouting, and escaped.

In school Fred couldn’t see the blackboard so his habitual answer to questions was, “I don’t know,” until someone discovered his handicap, brought him to the front of the room, and got him glasses. A math teacher took an interest in him and became a trusted friend. During eighth grade Fred was spewing water on a friend when the principal came around the corner and threw a paddle at him. The paddle broke a window and Buddy fled, never to return to the school. He and a friend hitchhiked to California and back, hopping trains and asking for day work sorting flour bags and doing cleanup in bakeries so they could feast on the day-old pies. After he returned to Philadelphia, Grammy Hann became sick and Buddy moved around among relatives. When Charlie married he tried to help by offering his brother a place to stay. He was rewarded with the job of cleaning up the mess when Buddy came home drunk and heaved up whatever he’d had to eat and drink.

Stealing cars put Fred in and out of jail until the parole officer said he must join the army or be put away “forever.” When he tried to enlist, the examiner told him that his eyes were not good enough for military service.

“But my parole officer said I must join,” Fred protested.

“What’s your name?” the officer asked.

“Holland,” he replied. The officer shuffled some papers.

“Oh, you’re in!” the examiner concluded, stamping the applications emphatically.

Fred chose to serve in the Air Force, which at that time was still part of the Army. He recalled that he fired every gun the Army owned. Sometimes trainers asked him, “How did you get in here? You can’t see!” He became the bar manager at the Army base, and often his friends brought him home drunk and put him to bed. In post-war Germany he and some military friends stole equipment from a camera store. Fred was persuaded to take the blame to save the others from losing rank and ended up in an annex of Sing Sing prison in New York State. Somehow the injustice was discovered and Fred was restored to service, where his drinking continued.

One night while he was stationed in Newport News, Virginia, he was out on the town when a student from Bob Jones University handed him a tract. Fred tore it into shreds and showered it over the head of the kid who dared to approach him. “What he didn’t know,” related Fred, “was that being reminded of my spiritual need was like having a knife thrust into my heart.” He later wished that the young man could know how he had turned to God and was living to serve him.

That’s up to you

In 1948, not long before he was to be discharged, Fred sat with a Coke bottle standing in his desk drawer filled with half Coke and half liquor. At age 22, he was worried about his future. He turned and said to his supervisor, “What would you think if I became a preacher?”

His boss answered, “You’d have to make a few changes, wouldn’t you? Why don’t you start by taking your GED to finish high school?” Fred passed easily. He was discharged in October and on his way home he went to the bar in the Philadelphia train station and ordered a double shot of whiskey with a beer chaser. He turned to the man beside him and declared, “That’s the last one I’m going to drink!” “Well, I guess that’s up to you!” the man retorted.

Fred went to Charlie’s house, and was invited to attend revival services on Sunday night. What he didn’t know was that the whole church had been praying for him. In his pocket he had a roll of bills from his exit pay intended for purchasing a car. He asked Charlie, “Do you think it would be okay if I took out the tithing now, so I don’t have to do it later?” Among the church members was a family who sang together. They had been invited to sing at another church that Sunday night but declined, hoping that Fred would be present, and announcing, “We want to be there when Buddy gets saved!” Pastor Charlie assured them that he didn’t think his brother was going to get right with God the very first night he was in church. During the service, however, Fred was under tremendous conviction. He went outside and ripped up his cigarettes, came back in, and went forward to the altar where he wept his way to salvation on October 17, 1948. He remembered anointing a huge spot on the floor in front of the mourner’s bench with his tears.

Fred quickly entered Bible school at a little place in Florida, but the school closed at the end of that semester. A friend brought him to see Messiah College. He liked to say that when he arrived on campus he felt a breeze from heaven telling him this was the place he was to be. But was Messiah ready for him? The rollicking personality of an ex-GI, ex-alcoholic, who could see the funny side of everything and tell jokes in strings, was another kind of breeze altogether. His personality called for a response and on one occasion when he came downstairs to breakfast in Old Main, he found that his friends had stuffed his little Crosley Hotshot car into the entrance of the chapel. They offered to help him down the front steps with it, but he said, “Don’t touch it!” and proceeded to drive the little car down the stairway.

Lest you think he was only a jokester, he took the messages about humility to heart and cut off his curly black hair because he felt he was too proud of it. But then a visiting speaker preached that brush cuts were worldly. It seemed he couldn’t win. On one occasion, a professor asked him when he was going to grow up. He was trying. He led gospel team groups on very serious missions but on the way home treated everyone in the car to pie and ice cream and non-stop jokes. Even though his tuition was paid by the GI education bill, he didn’t have lots of money and he needed other sources of income for room and board, so he began to pastor a little congregation to which Charlie’s church assigned him. He lived on campus the first two years, commuting to the church and recruiting other students to help him put up a small building. He learned to know George Bundy, who was headed for missions, and the two of them met for early morning prayer. Throughout Fred’s life, George was an encouragement to him.

One night Fred and his roommate, another ex-GI, were discussing the available ladies around them. “We decided that Grace Herr was the nicest girl on campus,” he liked to tell, “but we were sure she wouldn’t look at either one of us!” As our acquaintance deepened, I heard that he was asking other students if he was humble. When they asked why he wanted to know, he answered, “Well, doesn’t the Bible say that the Lord gives Grace to the humble?” We began dating regularly and I saw that the curly black hair that grew back certainly was attractive! His love for the Lord was attractive too. Maybe I could serve God with this man after all.

During his third year, Fred roomed off campus and on one occasion he attended a missionary meeting somewhere. He had $10 in his pocket for supplies for the week. When the offering plate was passed, he put in five dollars. He was amazed when they said they hadn’t received enough and passed the plate again. He looked around at all the other people who could well afford to contribute more, but ended up putting in the other five-dollar bill. In later sermons he would point out that God does not always restore immediately what we give. “I lived on coffee and crackers that whole week,” he would conclude, “but I had joy in my heart!”

During his three years at Messiah, Fred developed great respect for his professors and for the Brethren in Christ Church. He graduated with the first class to obtain the bachelor of theology degree. Years later he confessed that he figured he was not a good enough man to be a pastor but thought perhaps he could be a missionary. He applied to the Brethren in Christ mission board. There was a place for him in Africa, but he would need teachers’ certification. To earn this, he transferred to Greenville Free Methodist College in Illinois. Our correspondence grew warm and serious. He visited my home where he enjoyed the fresh milk, helped to store hay in the mow, and through a misstep sent one leg halfway down the chute for feeding hay to the cows. Fred was adjusting to my family and I was falling in love with him even though a few questions remained. We were working things out, and then a wrench was thrown into the works.

To buy a copy of the book and read the whole story, contact the editor. Copies are available for $10.00 each plus postage.