Flowers for Martha: Sentiment and Slippage in the Archives

“Let’s face it. I am a marked woman, but not everyone knows my name.” —Hortense Spillers, Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book

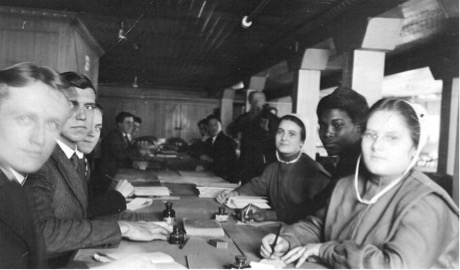

The photographer directed each student to gaze into the camera with one student standing out. You notice her immediately. Her Blackness shines here, in this black-white printed image.1 She sits between two white young women and across from three white young men. She does not dress in the traditional Brethren in Christ women’s attire of a bonnet and “plain clothing,” but she still follows the modest dress code of the time. She wears her thick, black hair pinned back, away from her face, in what appears to be a low bun. She stands still, pen in hand, interrupted by the photographer’s request. A full smile does not grace her face, but neither does a frown. She seems content. Under the photographer’s direction, her eyes gaze into the camera’s lens. Through this photograph, she finds a place in the school’s archive. The front of this image tells this story—the story of the first Black student at Messiah Bible School and Missionary Training Home.2 The back of the image tells a second story, one of slippage and misnaming in a college’s archive.

Known today as Messiah University, the institution initially identified this student as Martha Bosley. Born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania on March 29, 1909, Bosley attended Messiah Academy, the college’s high school from 1926 to 1929 and Messiah Bible School from 1930 to 1932.3 In The Clarion, the school’s yearbook, students left the following caption under an image of Bosley: “With banjo, song, and cherry smile, she makes the bluest days worthwhile.”4 Believed to be the first African American student to attend Messiah, this revelation contradicted a 1918 photograph of the student body in which another Black student appears. In 2009, Hierald Edgardo Osorto, alumnus and former Director of Multicultural Programs, revealed that the student in the opening photo and Martha Bosley were two different individuals.5 She, the student, was misnamed, and it took nearly a century for her to be properly identified. That year, a strikethrough appeared over Bosley’s name with the following caption to the side, “Rachel Flowers (incorrectly identified as Martha Bosley).”6

Read the rest here:

rachelflowers-aug2020- In the background you see a second, although blurred, photographer. Rachel Flowers in Class—1, 1916-1918, Messiah University Archives. [↩]

- A note on reading photographs: Drawing upon feminist historian and historian of photography Laura Wexler, Tina Campt challenged scholars to move past looking at photographs as merely “the way things were,” but rather read photographs as a record of intentions and a record of choices. She noted, “The question of why a photograph was made involves understanding the social, cultural, and historical relationships figured in the image, as well as a larger set of relationships outside and beyond the frame—relationships we might think of as the social life of the photo. The social life of the photo includes the intentions of both sitters and photographers as reflected in their decisions to take particular kinds of pictures. It also involves reflecting historically on what those images say about who these individuals aspired to be; how they wanted to be seen; what they sought to represent and articulate through them; and what they attempted or intended to project and portray.” Tina Campt, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 6. [↩]

- Martha Bosley’s School Records, Messiah University Archives, Grantham, PA. [↩]

- Messiah Bible School, The Clarion (Grantham, PA, 1932), 16, Messiah University Archives. [↩]

- In preparation for the college’s centennial celebration, Hierald Edgardo Osorto, class of 2006, then Director of the Office of Multicultural Programs at Messiah, began researching the first underrepresented students to attend Messiah College. As Hierald and his student researcher, Mollie Gunnoe, class of 2012, identified students, they determined that Martha, who later attended Messiah Academy (1926-1929) and Messiah Bible School (1931-1932) was the second African American person to attend the institution. [↩]

- Rachel Flowers in Class—1 (cropped), 1916-1918, Messiah University Archives. [↩]