Author’s Note: On April 24 and 25, 2004, I interviewed Anna Taylor Grissinger and Mabel Frey Hensel, both widows in their early nineties, in their homes at Messiah Village, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania. They had been missionary kids, the children of pioneer missionaries to Africa, Myron and Adda Taylor and Harvey and Emma Frey, respectively. My interest in talking with them stemmed from my own experiences in Africa, and from a desire to know more about my missionary relatives. Anna’s mother, Adda Engle Taylor, was first cousin to my great-grandfather M.G. Engle. Mabel was first cousin to my grandmother Minnie Lady Engle. The interviews with my newly met cousins were informal; I made hand-written notes. I told them of my intent to include their memories in a book I was writing. I had two, ninety-minute sessions with Anna, over two days. I spent ninety minutes with Mabel, and followed up with written correspondence.

Six-year-old Anna Taylor lifts her eyes to the twinkling expanse of the African night sky and makes a wish:

Star light, star bright

Hear the wish I wish tonight

I wish I may, I wish I might

Have the wish I wish tonight:

To see my sister…

The year is 1919, the place Sikalongo Mission—a beautiful, remote station in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) founded by Anna’s parents Adda Engle and Myron Taylor.[1] Anna’s heart is heavy as she petitions the heavens—something she will continue to do for many months. She and her parents had recently parted with Anna’s only sibling—eight-year-old Ruth—putting her on a train to Cape Town, and then the long ocean voyage to America. Six years would pass before the Taylors would see Ruth again.

“Did they show emotion when Ruth left?” I asked.

“I never saw Mother or Father cry,” replied Anna.

Adda Taylor’s older sister Elizabeth Zook—a childless widow who had already adopted a daughter and taken in a needy single woman—had offered to take one of Adda’s girls into her Abilene, Kansas home, and to oversee her education. For Anna, the childhood loss of her sister’s companionship was still poignant, eighty years later. Tears rolled down her cheeks as she told me: “Ruth was a leader and I followed her; now I was an only child.”

A year after Ruth Taylor’s departure for Kansas, Beulah Musser arrived from the U.S. to assist the Taylors at Sikalongo and a school was established. Beulah was thirty-three, and a third cousin to Anna on her mother’s side.[2] Anna said: “I followed her [Beulah] everywhere!”

Anna also gained another “big sister”—Musunse—a Tonga (African) teenager who worked for the Taylors when they served at Macha Mission, which had been co-founded by Frances Davidson and Adda Engle in 1906.[3] She then accompanied them to Sikalongo in 1916.

“I think Mother thought she [Musunse] would be good for me,” said Anna. “Musunse would take me with her to get water and tell me stories about how the animals got their horns.”

Bush life offered both excitement and danger. Anna was with her mother in the kitchen one day at Macha Mission when Frances Davidson, who had gone to the chicken coop to get eggs, came running and yelling, “Get the permanganate quick!” A cobra had spit poison in her eyes.

Every missionary home had its bottle of potassium permanganate—the purple water-soluble crystals that could be dissolved in various strengths and used as disinfectant, astringent, or antiseptic. Frances treated herself, but got the solution too strong and burned her eyes. She had to stay out of the sun for several days while her eyes healed.

Anna recalled a time (at age four or five) when she was “really scared” at Sikalongo: “Father had an infected foot—he had cut it while cutting logs and was lying in bed on a Sunday afternoon. Mother and Ruth were in the house with him. I was playing just outside the screen door with a cat and heard a sound like dragging on gravel. A snake was coming towards me—a black mamba (one of the deadliest snakes in Africa). I ran inside the house and slammed the door—something I wasn’t supposed to do—and said, ‘A big snake!’”

Myron went after the snake with a stick, but the fast-moving creature got into the house and coiled itself around Myron’s leg. He yelled for some nearby Africans, who came running with their spears. By this time the agitated snake had slithered into the kitchen, onto the kitchen table, and back to the floor again. The Africans, aiming through open windows, pinned the mamba to the floor with their spears.

Anna’s closest age mate among the missionary children was Mabel Frey, the youngest child of Harvey and Emma Frey—founders of Mtshabezi Mission in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).[4] Anna noted that her mother Adda and Mabel’s mother Emma were “very good friends,” having traveled to Africa together in 1905. There were visits back and forth between the mission stations.

Both Anna and Mabel described happy times provided by loving and imaginative parents. Mabel had a playhouse and a swing, noted Anna, with remembered longing. Then she added, with a smile: “But her parents were stricter than mine were.”

Anna played with a kudu (a common African deer) her father brought home one day, suggesting it would make a good pet. Mabel adored her own pets—the dogs Tessie and Tinker.

Mabel’s father once took Tinker along on a journey to visit outstations he had established in the Wanezi area of Southern Rhodesia. Harvey traveled by mule cart, with driver Gwanyana Ncube; his journeys were frequent and “he would be gone for weeks at a time.” But he kept in touch with Mabel, as noted in a brief piece she wrote about him:

One day—imagine my surprise and joy—a letter came from Tinker! I hadn’t known my dog was a writer! He gave me all the news about Daddy and himself. I still have his wonderful letter. So I decided to write a letter to Tinker. “Responsible Government” (R.G. as it was called) was being talked about at the British school I attended. I didn’t understand it, but was all for it. So I wrote a letter and addressed it to Mr. R.G. Tinker, c/o Harvey Frey, and sent it to the local address—probably a tiny store in the area that also served as a place where mail could be sent…. Daddy finally got the letter and wondered who in the world was Mr. Tinker. He knew of no one in the area of that name. Finally his driver said: “Ah! It’s the dog.”[5]

“Daddy taught me until I was nine,” said Mabel, “and then I had a short period at Eveline boarding school before we moved to Bulawayo, when I became a day student.” Anna Taylor went to school with Mabel for awhile, during which time Anna lived with the Freys in Bulawayo.

While living in Bulawayo, Anna received weekly letters from her mother. “Mother was a writer,” said Anna. “She kept in touch with family.” One week Anna did not receive a letter, and got worried, but later she learned her mother had been away on a village visit.

Mabel said “letters were a lifeline” between herself and her parents during their times apart. At the end of a mid-1920s furlough, Mabel stayed in California with her mother in order to finish high school, while Harvey returned to Africa. Upon her graduation, Harvey wrote to Mabel:

You are just beginning to look out upon the great ocean of life with all its possibilities, trials, dangers, difficulties—but with all the victories, blessings and crowns as well. How glad you may be that you have a Captain for your ship who knows the way and who ever cares for you. Trust Him and obey Him implicitly, my dear daughter, and you need never fear any trial or danger. Can it be that my baby daughter is so nearly grown? Only a short time ago you used to want your father to take you in his arms and carry you outside every time he put on his hat.[6]

Mabel was preparing to begin her own missionary career when she learned her father had prostate cancer. Harvey wrote to his daughter: “We know you will remember that ‘underneath are the everlasting arms.’” Mabel noted that during his illness and final months of life, “Father wrote his book [on holiness] for the Africans. My parents were both fluent in Sindebele.”

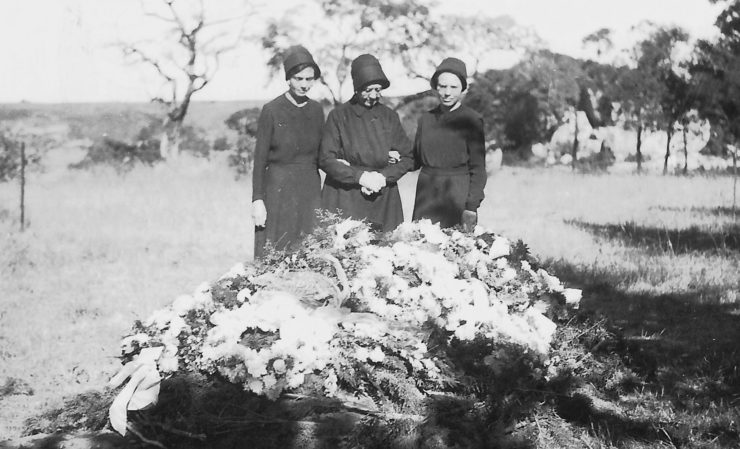

Mabel returned to Africa in 1936, just prior to her father’s death at Matopo Mission. Harvey Frey was sixty-three when he died on May 28, 1936.

At a time of grief, Mabel was able to return to her childhood home at Mtshabezi Mission where she taught domestic science to young African girls. She served nine years without a break as World War II prevented travel to the U.S. when she was due for furlough in 1943. She spent a second mission term at Mtshabezi, and a third term at Wanezi Mission, teaching in the Bible School. Her students at Wanezi were “mostly older preachers or teachers that had had very little education but wanted to learn more about the Bible and how to share it.”

Mabel returned to the U.S. in 1963 to be near her mother who was not well. Emma Frey died the following year. Mabel married widower David Hensel in 1968. Mabel’s niece writes: “Uncle David’s foster son, Bud, and his family took Aunt Mabel into their hearts and she inherited four grandchildren and over twenty great grandchildren.”[7]

Anna’s father also died in Africa, following attack by a wounded lion. Myron Taylor was on an evangelistic mission in the Zambezi Valley southeast of Sikalongo when he offered to help track a lion that was terrifying the local people. A Brethren in Christ mission history book describes what happened: the setting of a trap, the lion dragging it away, Myron tracking the animal, using a borrowed rifle that jammed, the lion mauling Myron and biting deeply into his left forearm, faithful workers carrying Myron back to Sikalongo by foot, thirty miles over hilly terrain.[8]

Myron and his helpers arrived at Sikalongo in the early hours of the morning and word was immediately sent to the doctor in Choma, the nearest town. Adda was out on an extended village visit at the time; an African worker was sent to tell her the news. She returned to Sikalongo to find that her husband’s arm was gangrenous and would have to be amputated to save his life.

The Choma doctor needed the help of a surgeon to perform the operation. The nearest one worked in Livingstone, some one hundred miles away. The surgeon traveled to Choma through the night by special rail transport and arrived at Sikalongo the following morning.

Anna said her father told the doctor: “If you give me anesthesia, I won’t survive.” Myron Taylor had some medical knowledge and skills, according to Frances Davidson, with whom the Taylors worked at Macha Mission. Davidson, writing about developments at Macha during the year 1912, notes: “Both Mr. and Mrs. Taylor were quite successful in medical work, and some difficult cases came for treatment. In this year Brother Taylor treated some very severe wounds, ulcers, cancer, a boy with his hands blown to pieces by gunpowder, a native badly lacerated by a leopard, and an European who had accidentally shot himself, in addition to other cases.[9] Myron was fifty-eight when he died on September 16, 1931, while under anesthesia.

As it happened, the attending surgeon was also a Reuters press agent, and so the news of Myron’s death went out on the wires around the world. Anna’s sister Ruth—at school in Grantham, Pennsylvania—first learned of her father’s death by reading about it in the newspaper.

Anna was in Bulawayo at the time and heard the news of Myron’s death in a slightly more personal way. The publisher of local newspaper The Native Mirror, an Australian by the name of Hadfield, was a friend of the missionaries and acquainted with Anna. When he received the Reuters wire about Myron’s death, he took the news to the headmistress at Eveline School, who informed Anna.

Mr. Hadfield drove Anna to Matopo Mission and told the missionaries of Myron’s death. A couple days later Elizabeth Engle Steckley (missionary nurse, first cousin to Anna’s mother) and Harvey Frey drove Anna to Sikalongo, arriving a week after Myron’s death.

“How was your mother coping?” I asked.

Anna replied: “Mother tried to keep things together. She was put in charge of the mission. She also tried to inform everyone at home [about Myron’s death]. When she made the decision to go home [to the US, the following year], she said, “The decisions are made. I’m not even informed. I might as well go home.”

Anna left Africa with her mother in 1932. Having completed Form 4 at Eveline School in Bulawayo, Anna enrolled in and graduated from Messiah Academy (high school) in Grantham, Pennsylvania. She tried college, but “it did not go well…I wasn’t well…had a nervous breakdown.” Anna identified two stressors: her father’s death and adjusting to a different, less-structured educational system in the U.S.

Anna and Adda went to Kansas for awhile to help Adda’s sister Hannah Brechbill during her husband’s illness. Someone asked Anna at the time, “How will she [Adda] accomplish all that…” Anna replied: “I don’t know…mother will find a way.” Anna then told me of her mother’s numerous domestic skills: “Mother could cook over an open fire and bake bread and use hammer and nails. She made frames for our beds and sewed up corn husk mattresses.”

Later Anna worked at Paxton Street Home in Harrisburg, PA. There she met a widower, Arthur Grissinger, who had one son. Anna and Arthur married in 1950.

Anna died in 2007 and Mabel in 2008. I have since thought of other things I could have discussed with them. What a wealth of knowledge and wisdom our elders have to share; we need only ask and listen.

Endnotes

[1] Anna R. Engle, J.A. Climenhaga, and Leoda A. Buckwalter, There Is No Difference: God Works in Africa and India (Nappanee, IN: E.V. Publishing House, 1950), pp. 130-134.

[2] “Draft Descendant Genealogy of Ulrich Engel & Anna Brachbuhl 1754-2004,” Engle Family Association, 2004.

[3] H. Frances Davidson, South and South Central Africa (Elgin, IL: Brethren Publishing House, 1915), pp. 237-262.

[4] Engle, Climenhaga, and Buckwalter, pp. 93-99.

[5] F. Mabel Frey, “My Father, Harvey J. Frey, undated and unpublished manuscript, p.1.

[6] Ibid., p. 2.

[7] Ruth Barham Bell, personal communication, November 2014.

[8] Engle, Climenhaga, and Buckwalter, pp. 136-137.

[9] Davidson, pp. 421-422.