I was about to enter the eighth grade in the summer of 1939 when the German blitzkrieg rolled across the Polish border on the first day of September. Two days later Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. Little did I realize that the United States would become involved, and I would be called for service. Even when my brother Millard entered Civilian Public Service (CPS) in February 1943, I did not give serious thought to the fact that the war would drag on and I would be drafted.

I registered upon reaching my 18thbirthday on April 29, 1944. The registration certificate noted that I was approximately 5′ 8″ tall and weighed approximately 115 pounds. I was a member of the Brethren in Christ Church, one of the Historic Peace Churches. In accordance with the nonresistant position of the church and my own personal beliefs, I requested classification as a conscientious objector. The next month I received the Notice of Classification and was classified IV-E.

A pre-induction physical examination was required, and I received an order to report to the American Legion Building in Mount Joy at 6:45 a.m., September 18. There were other young men to be examined, and the group traveled to Harrisburg by train for the physicals. I will not forget the experience. During the examination each individual was required to wear his birthday suit. Obviously, many people had to be examined, and one official had developed a routine to speed up his part of the work. His instructions, given in a sing-song voice, went something like this: “Next man step right up (on a scales), hands up, hands down, bend over (and so on).” As his instructions were followed, he called out one’s height, weight, and other important information which was recorded by another official.

Speed was an important factor, but some examinees slowed the process. Their lack of coordination was all too apparent. Some had their hands up when they should have been down and down when they should have been up. Their failure to follow instructions threw the examiner off his rhythm and seemed to annoy him. It was rather funny, but showing amusement was not appropriate.

I was given a Certificate of Fitness certifying that I was “physically fit, acceptable for general military service.” The form was stamped with the signature stamp of First Lieutenant Claire London, WAC, Induction Station Commander.

In December, I received the “Order to Report for Work of National Importance” from the President of the United States. That is probably the only time I received a communication from the chief executive of the nation. Of course, it was a standard form, and the information was completed by people from the local draft board. I was ordered to report to Local Board No. 1 at the American Legion Building in Mount Joy at 4:00 p.m. on January 4, 1945, where I would be given instructions to proceed to the camp at Grottoes, Virginia. A letter from the clerk of the local board informed me that the train to Grottoes would leave from Lancaster at 6:11 a.m., Friday, January 5.

I left from Lancaster with a number of other men who had been assigned to Grottoes and arrived at Civilian Public Service Camp No. 4 at 3:45 p.m. The camp was located in Rockingham County on the lower slope of Austin Mountain in the Blue Ridge Mountains less than four miles east of the small community of Grottoes. It was outside the Shenandoah National Park and about five miles from the Skyline Drive. It had been a Civilian Conservation Corps camp under the National Park Service.

Grottoes, Virginia

The camp was an attractive and well-maintained facility. There were four large barracks, a large dining hall, a number of offices, a chapel, an infirmary, and various supporting buildings, all of frame construction.

After being assigned a bed in Barracks No. 4, I was informed by fellow campers that the man next to me was a hard character. It was an attempt at a joke as his name was Weir Stone. He was tall, muscular, and physically robust. He was trained as a parachutist and had served at a camp for “smoke jumpers.” These men fought forest fires in areas that were not easily accessible by vehicle.

Living in a barracks and eating in a common dining hall, constantly surrounded by men from varying backgrounds, was a new experience. The schedule called for rising at 5:45a.m., breakfast at 6:15, and reporting for work at 7:30. Work ended at 5:00 p.m. and supper was served at 5:30. At the time of rising, and again at retiring, religious music was played over the public address system.

The first several days at camp were spent in orientation including instruction in safety measures to observe at work. The major work performed was related to soil conservation. It included clearing pasture land of brush, planting seedlings, taking measures to reduce erosion, tearing down and building fence, and installing drainage tiles. Occasionally there was a forest fire to fight. The work had some value, but to designate it as work of national importance was stretching the point.

Men were assigned to various work crews. In the morning, Monday through Saturday, crews rode to work in the back of canvas-covered trucks. Each crew had a foreman who assigned and directed the work. Bruce Grove, who later became a minister in the Brethren in Christ Church, was the foreman of the crew to which I was assigned. A full complement of tools was carried including digging irons, brush hooks, axes, shovels, wire stretchers, and wire cutters. At noon the men gathered near the truck to eat the meal that was packed that morning by the kitchen crew. It consisted of sandwiches and soup or chocolate milk which was heated over an open fire made by the truck driver. Every camper remembers the “choke” sandwiches made from peanut butter and honey.

Insert photo

I spent considerable time clearing pasture land and digging post holes. One day I dug holes with enthusiasm. Another camper and I decided to have a race to see who could dig the most holes. I do not recall who won or how many holes we dug, but at that stage of life we had more enthusiasm than common sense.

“Weather days” occurred occasionally. These were days when the work crews stayed at camp because of rain or snow. This gave individuals additional time to pursue their own interests.

During the evening hours men spent their time reading, playing games, writing letters,

making craft items, and participating in organized activities such as Bible studies and singing. Campers were able to enjoy a number of instructional and cultural activities, since Eastern Mennonite College [now University] was about 20 miles from the camp. Occasionally, faculty members came to camp to lead a Bible study or choral groups came to present musical programs. Table tennis was a popular activity, and I became well-known for my ability to play the game. On Saturday, March 31, I took first place in a playoff.

Campers looked forward eagerly to weekend passes and furloughs. My first weekend pass was on February 17 and 18. I also had weekend passes on April 14 and 15, April 28 and 29, and May 5 and 6. I had a short furlough from March 24-27, and a longer one from May 12-20. On most weekend passes campers were permitted to leave after work on Saturday. They had to be back for project work Monday morning, so the time at home was short.

Ample opportunity existed to attend religious services. Sunday school and worship were conducted each Sunday morning, and a service was generally held each Sunday evening. Prayer meeting was scheduled each Wednesday evening. In addition, a study on the book of Romans was conducted over a period of about 10 weeks by a staff member from Eastern Mennonite College.

At times, Brethren in Christ ministers visited the camp and preached during the Sunday services. Rev. Charles Rife preached on February 11, and Rev. John Martin preached on April 8. Other Brethren in Christ ministers may have been at camp when I was home on weekend passes or on furlough.

In May a large number of men were transferred to CPS Camp No. 35 at North Fork, California. I was included in that group. The transfer to North Fork is one experience I shall not forget, but do not wish to repeat. A water blister developed on my hand from working on a project and it became infected. The camp nurse examined my hand and decided that I would be able to make the trip to California.

We left Grottoes on May 22 and traveled by military railroad car. These cars were equipped with bunk beds and were comfortable enough for someone not experiencing any physical difficulty, but I experienced more and more discomfort as the trip progressed. When the train arrived in St. Louis, I was taken to the station doctor for an examination. He was of the opinion that the hand was not ready to be lanced and suggested it be examined when the train arrived in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

After we left St. Louis, the infection became more severe. My hand swelled from the fingers to the wrist and became very dark, bordering on black. To compound the problem, it was my left hand, and I am left-handed.

A doctor had been contacted and was waiting at the station when the train arrived in Albuquerque. He took one look at the infected hand and told me to accompany him to the hospital. I had very little money, and as I left the train fellow campers pressed bills into my hand. In my haste and discomfort, I left one of the few hats I ever owned on the railroad car. Dr. Derbyshire took me to the hospital in Albuquerque at noon on Friday, May 25.In preparation for an operation, a nurse tried to put me to sleep. The nurse, who was about to inject sodium pentothal into my arm, told me to begin counting. She said that I would be asleep before I reached 10. I began to count, reached 10 and beyond, and was still wide awake. She missed the vein, so the doctor took the needle and showed her how it should be done. I was soon asleep. My hand was lanced, drained, and packed. I was a patient in the hospital for five days.

When I was discharged, I did not have enough money to pay both the hospital and the doctor. Dr. Derbyshire told me to pay the hospital bill and settle his account by mail. The North Fork Camp officials took care of the matter, and I suppose the bill was paid by the Mennonite Central Committee. When one thinks about medical costs today, the charges I incurred are hard to believe. The hospital bill amounted to $26.60, and Dr. Derbyshire, who performed the operation, charged $25. Over 40 years later, I asked Gladys Lehman, my wife Janet’s cousin, who worked in the health field in New Mexico and lived near Albuquerque, whether she had ever heard of Dr. Derbyshire. Surprisingly, he was still living and she knew him.

The remainder of the trip to California was much more enjoyable. I left the hospital on Wednesday, May 30, and traveled by Pullman, arriving in Fresno about 10:30 on Thursday evening. The camp director, Jacob Goering, met me and took me to North Fork, where we arrived about midnight.

North Fork, California

[Insert photo 2. Caption:“Motel Grottoes” at Camp #35, North Fork, CA, where the men lived who had been transferred from Camp #4, Grottoes, VA.]

Camp No. 35, a former Civilian Conservation Corp, was located 50 miles northeast of Fresno in the foothills near the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It was less than one mile from the little village of North Fork.

[Insert photo 3. Caption: Eugene Haas, another CPS volunteer, in the quarters he and I built under “Motel Grottoes.” It was later enclosed.]

Due to the condition of my hand, I was placed on sick quarters, where I remained for 13 days. The day I was taken off sick quarters, and the previous day, I helped to take inventory. The following day I was assigned to a project crew involved in road work. I was probably given strenuous work too soon, for trouble developed with my hand at the site of the incision. I was placed on sick quarters again where I remained for eight more days.

In the weeks that followed I was assigned various types of work. For a short period of time I worked in the laundry and became quite accomplished at ironing shirts. After that I worked for a week on a road crew. Then I was among a group of men called out to fight a forest fire. We left on Saturday evening and returned to camp Monday evening. My next assignment was in the dining hall and kitchen. I worked as a waiter and then as a cook for the remainder of my stay in California.

One morning, while the road crew was on its way to work, young coyotes started to cross the mountain road. The truck driver succeeded in hitting and killing one. We stopped to examine it The coyote was a pretty little animal.

In July, and again in September, I was sent with other campers to fight forest fires. Fighting forest fires, I discovered, is hard work. If a fire is to be contained, a fire line must be constructed as rapidly as possible. Several men with axes led the way. Their job was to cut away the larger growth. They were followed by men with brush hooks who cut away the smaller brush. Next came men with rakes who cleared the debris from the path made by the men in front of them. Then men with shovels dug ditches where necessary to prevent burning logs from rolling across the fire line and starting new fires. Finally, men carrying backpack water tanks equipped with pumps patrolled the constructed line to extinguish small crossover fires that occasionally occur. Sometimes backfires were started to help contain the blaze.

I remember on one occasion coming off the fire line at the end of the day tired and very thirsty. A field kitchen was set up near the area of the fire. While eating the meal, I drank cup after cup of coffee to alleviate my thirst. After the meal, sleeping bags were issued and we slept under the stars. At the end of the next day, with the fire under control, we hiked a considerable distance to reach the trucks that took us back to camp. One of the “rewards” of fighting forest fires was poison oak. I got a good dose each time and spent a number of days on sick quarters.

I was on sick quarters again in September. This time it resulted from dental work. A mobile dental unit, operated by CPS men, came to camp to give examinations and perform dental procedures that campers agreed to have done. From my youth I had trouble with my upper teeth. While I was in high school, four front teeth were extracted and a partial plate was made. Many of the remaining teeth had been filled, but they were not very substantial. I agreed to have my upper teeth extracted and a full plate made.

The impressions and the new plate were made before the teeth were extracted. On September 7, I was injected with Novocain, given “laughing gas,” and had 13 teeth extracted. My gums were lanced to reach several molars that had not yet emerged. Before leaving the chair, my new plate was put in place. Needless to say, I had one sore mouth! I spent four days on sick quarters that time.

I finally advanced to the position of cook. That required rising early in the morning to prepare breakfast and remaining on duty until the kitchen was cleaned after the evening meal. A redeeming aspect of this work was that cooks worked one day and had the next day off.

[Insert photo 4. Caption:Barracks at Camp #35.]

Days off from working as a waiter, and later as a cook, gave me an opportunity to work away from camp and earn some much needed money. Men inducted into CPS received no pay from the government and only a very small allowance of several dollars a month provided by the denominations that supported the program. A man by the name of Freeman had a number of cottages and a store at Bass Lake, a resort area about twelve miles from camp. On one occasion I earned $7 and on another I earned $5working for him.

One Saturday I went to work for Freeman with the understanding that another camper would take me back to camp at the end of the day. He completed his work, forgot about me and returned to camp. I was not overjoyed at the end of the day to discover I was stranded. I had little choice but to start walking. A motorist gave me a short ride, but I walked most of the way. Darkness fell long before I arrived at camp. The area was thickly forested, and I had an eerie feeling as I walked along. Fortunately, I was not abducted nor devoured by a wild forest creature.

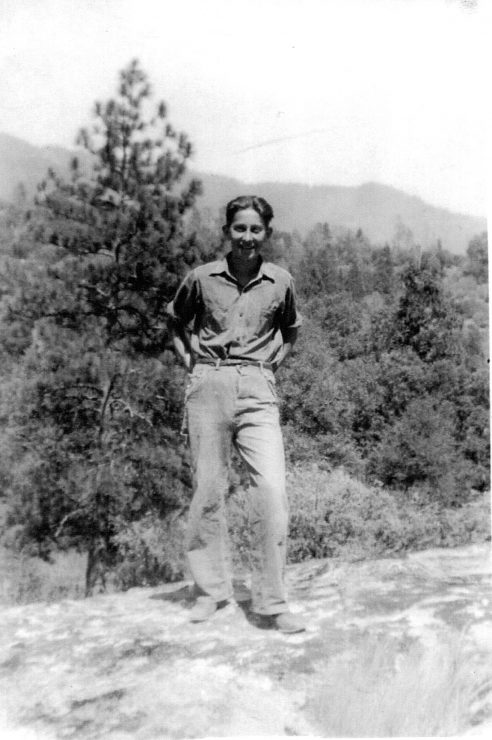

[Insert photo 5. Caption:The author at Camp #35.]

Another place I worked was at Goodman’s sawmill which was not far from camp. Mr. Goodman operated the large saw which cut the logs into boards. An American Indian stacked the lumber as it was cut, and I used a smaller power saw to cutup the slabs which contained the bark and put them on a conveyor that dumped them into an incinerator. I received a check in the amount of $18.75 for 22½ hours of work.

An enjoyable recreational activity was swimming. There were a number of places where a camper could enjoy the sport. On the east side of the camp, the terrain sloped perhaps 50 feet before rising sharply to become the side of a mountain. A stream flowed at the bottom of the ravine, and through the years the water eroded the granite rock into interesting formations. At one place a sizable pool had been formed and diving was possible. I enjoyed swimming in the cool, clear mountain water.

Campers could also swim at the compound pool. The Forest Service office and maintenance buildings were located near the camp. This area was referred to as the compound. By road it was perhaps a mile or two, but a path led from the camp, down a ravine, and up to the compound, so it was easily accessible. Bass Lake was the best place to swim, but it was used less frequently because it was 10 miles from the camp. Another form of recreation was outdoor badminton. I spent many hours playing under the hotCalifornia sun.

A number of the men who transferred from Grottoes knew about my table tennis ability and were interested in a match between the North Fork champion and me. Merle Mead, the champion, at age 37 was one of the older campers. He stood close to the table and scarcely moved his feet or body as he moved the paddle from side to side returning shot after shot. Apparently no one at camp had been able to beat him.

One day I was in the recreation room and asked Merle if hewould play a game. He agreed. Much to his surprise, I won the game. He was not accustomed to losing and wanted to play a second game. I won again. We played a third game which I also won. I could slam returns and would do so when the opportunity presented itself, but I was primarily a defensive player. I stood at a considerable distance from the table to return my opponent’s shots. The fact that I played left-handed may have given some players trouble.

One of the most pleasant experiences during my time in CPS was singing in a male quartet. The members were Eugene Haas, second tenor, from Dryden, Michigan; Harold Duerksen, first tenor, from Hillsboro, Kansas; James Detweiler, bass, from Hydro, Oklahoma; and I who sang baritone. Harold was a General Conference Mennonite, James was an Old Mennonite, and Eugene and I were Brethren in Christ.

[Insert photo 7. Caption:The North Fork quartet. Left to right: Harold Duerkson, Eugene Haas, Morris Sherk, and James Detweiler.]

Eugene was primarily responsible for forming the quartet and arranging a full-length program which included approximately 14 numbers. We memorized most of the songs and sang a cappella. Our first program was given at camp on Sunday, October 21.

The weekend of 0ctober 26 and 27 we went to Upland. We left camp Friday evening and arrived in Upland about midnight. I slept at the home of a family by the name of Trautwein. I ate the Saturday noon meal at the home of Wallace Stump and the evening meal a the home of Roy Roth. Saturday evening the quartet presented a program at the Old Mennonite Church. That night I stayed at the home of the Warren Sherman family. Warren’s wife Anna Mae was my first cousin.

Sunday morning we attended Sunday school and sang during the worship service at the Upland Brethren in Christ Church. We were given the noon meal by the Ralph Byer family of the Upland congregation. There were several very lovely daughters in that family. The Byer girls took us to the General Conference Mennonite Church early that evening where we gave a program which was followed by a social hour. After that we sang several numbers at the Upland church before leaving for camp at 8:15. We arrived at camp after 5:00 the following morning.

Our quartet presented a program at a church in Fresno on Sunday evening, November 4. That day I was in the home of Irvln Jennings for dinner. On the evening of November 8, a fall banquet was held at camp, and our quartet sang several selections.

After leaving North Fork, I lost track of the other members of the quartet. It was nearly two years later that I crossed paths with Eugene Haas again. We were students at Messiah Bible College, now Messiah College, during the 1947-48 school year. He was a sophomore and I was a freshman. Eugene went on to earn his Ph. D. in sociology and was a university professor. I have not seen Harold Duerksen again since our time together in camp.

Forty-five years passed before I met James Detweiler again. I had no idea where he lived or what he was doing. In June 1990, my wife Janet and I attended a North Fork CPS reunion at Goshen College. One of the men mentioned James in one of the sessions. After the meeting I went to the man and asked if this was the James Detweiler who was formerly from Hydro, Oklahoma, and he said it was. Surprisingly, James lived a few miles from Goshen and was the pastor of a Mennonite congregation. Janet and I drove to his house and had a very pleasant visit. When he saw me, I looked somewhat familiar to him, but after 45 years he could not make the connection. James did not know about the reunion; apparently the committee did not have his present address. While visiting with them, we made an interesting discovery. Janet and his wife Phyllis were classmates at Goshen College.

In October 1990, we were back at Goshen College for Janet’s 40thclass reunion. The Detweilers invited us to their house for the Sunday evening meal and to a Mennonite church where James was to be the guest speaker. He preached an excellent message.

At the General Conference at Messiah College in July 1994, Janet and I spoke with Jonathan Stepp who was employed by Evangel Press. I had consulted with him on the congregational history I had previously written. Jonathan married a Mennonite and they knew the Detweilers. Janet and I were distressed to learn that James died on April 29, only two months previously. He had been ill with cancer for several months.

For the last seven weeks of my stay in California, I was assigned to a side camp and had to leave the cozy quarters that Eugene Haas and I constructed. When the group of men from Grottoes arrived at North Fork in May, they were assigned to a new barracks which was nicknamed “Hotel Grottoes.” It was built on a slope with the entrance end at ground level. The other end of the building was perhaps eight feet from the ground. Eugene and I constructed our own little house under the barracks. There was plenty of slab lumber available that had bark on one side. This we used to construct our house. We even had an electric heater for the cool mornings. I was informed our house was used for storage after we vacated the place.

Eugene and I were sent to a side camp at Trimmer on Tuesday, November 13. Trimmer was located 40 miles from the base camp. Approximately 20 men were assigned to the camp. The main structures included the living quarters for the Forest Service employee who directed the work, a barracks for the men, and a building that contained the kitchen, dining area, and sleeping quarters for Eugene and me. We did the cooking, and Noah Troyer, an Amish camper from Ohio, was our helper and waiter. The Kings River was a short walk from the side camp. Some years later Pine Flat Dam was built, and a large lake, Pine Flat Lake, now covers the area.

While stationed at North Fork, I had the opportunity to go to Upland a number of times in addition to the weekend the quartet went there to sing. On the evening of November 9, I went to Upland with Maynard Book, who was the camp dietitian, and stayed with Warren Shermans. On Saturday evening I went to Los Angeles to a youth rally. On Sunday I attended Sunday school and the worship service at the Upland church, and in the evening I attended the revival service at which Henry Ginder was the evangelist. On Monday I visited Beulah College and then returned to camp. Toward the end of November, I visited Upland again on a four-day pass.

In early December I wanted to go to Upland on a weekend pass, but there was a problem. I was working at the side camp about 40 miles from the base camp. I had Friday off and had to get to the base camp for the ride to Upland. There was no transportation, so I set out by foot. Very few vehicles used the road that I had to travel, but I did get a ride for part of the distance. I wish I had a record of the number of miles I walked and ran that day.

My last visit to Upland was during the latter part of December. I went to Upland on Thursday evening, December 20. On Saturday I attended a basketball game at Beulah College, and on Sunday I attended Sunday school and the worship service at the Upland church. On Sunday evening and on the following Tuesday, Christmas Day, I attended Christmas programs. Christmas Day I went caroling early in the morning and later attended a basketball game. I was invited to Mabrie Goins’ parents’ home for Christmas dinner. At 3:00 p.m., I left Upland to return to the side camp.

I had made arrangements to meet a fellow camper in Fresno to take me back to the side camp. When I arrived at the designated meeting place, he was not there. Since I was scheduled to cook the next day, it was imperative that I find transportation. After waiting for a period of time, I asked a taxi driver what the fare would be to take me to the side camp. Upon being informed that it would be 50 cents a mile, I decided to wait, hoping my driver would appear on the scene. Finally, in desperation, I took the taxi. I had only a general idea how to get to the side camp, and I suppose the driver wondered to what place he was being directed. We arrived at the side camp, and I parted with $20, a large sum for a camper in those days. The 40-mile drive gave me an opportunity to tell the taxi driver about being a conscientious objector and about the work I was doing. I hope he found his way back to Fresno.

It was late that night, or early the next morning, when I arrived at the side camp. Being very tired, I overslept. When the ranger opened the door of my room and asked if I intended to prepare breakfast, I sprang into action.

Exeter School, Rhode island

At the end of 1945, I received a transfer to a training school for people with mental defects. Saturday, December 29, was my last day of work at the side camp. I returned to the base camp and attended Sunday services there the next day. The following day, December 31, at approximately 2:00 p.m., I left for home from the Fresno railroad station.

[Insert photo 8. Caption:The author at Unit #117, Exeter School.]

On January 21, 1946, after a furlough of three weeks, ! reported to Unit No. 117 at the Exeter School, Lafayette, Rhode Island. The conscientious objector unit was small, probably never exceeding 20 men. The facility was located in the country and included a dairy farm.

I was employed as an orderly and worked during the day. The shift was from 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. with, as I recall, one hour off in the afternoon. The area where I worked was in the basement of a building. The floor was of concrete, and benches, on which the patients sat, were arranged along the walls. There were very few windows and the ventilation was minimal. Patients regurgitated, urinated, and had bowel movements in their pants and on the floor. Some rubbed feces on their heads and faces.

[Insert photo 9. Caption:Wards 1 and 2 at Unit #117, Exeter School.]

I remember the first day on the job very clearly. As I descended the steps into the basement, the stench was nearly overwhelming. Drawing on a cliché, it was so thick you could have cut it with a knife. A large black boy approached, put an arm around me, smiled, and said, “I like you.” It was quite an introduction to a world that was entirely foreign to me. Surprisingly, after a time, I became accustomed to the stench.

Although some of the patients were mentally ill, most of them had serious mental defects and disabilities. Some were so deficient they could not talk nor control their bodily functions. A number had epilepsy.

Their diet was usually a sort of soup, or gruel, and large slices of plain, white bread. On many occasions the soup appeared to be made out of potato peelings. Considering the physical condition of the patients, many without teeth, a soft diet was necessary. One had to be very observant at mealtime. When a patient regurgitated, some who were able jumped off the bench to supplement their diet.

[Insert photo 10. Caption:The more able residents at Unit #117 on a work project.]

The patients were a most interesting group. Most were stunted in growth. Some had physical deformities. Although many were young, it was very difficult to judge their ages. A few had very strange behavior. One patient, completely devoid of hair, placed one hand in front of himself as if holding an object, and with the other hand he made motions as if he were sewing with a needle and thread. While making these motions, he repeated the phrase, “Pea soup and French.”

Another patient was naked most of the time. To keep clothes on him would have required constant restraint. There were times when he clasped his hands together and hit himself on the forehead. He had done this over such a long period of time that his forehead was extended. He hit himself with such force that he grunted each time.

A patient who was called “Hattie” had a can and a cloth which he used to clean up the feces and urine from the concrete floor. After a patient had a bowel movement or urinated, a call was made, “Hattie, cleanup the floor.” Hattie responded mockingly, “Hattie, cleanup the floor.” He was capable also of cursing a blue streak.

Substantial union suits were worn on the patients, but there were some who limited the life of the suits. As they sat on the benches around the walls of the room, some patients pulled their suits apart thread by thread and ate the threads.

On days when the weather was favorable, I took those who were able on outdoor walks. Walking in the fresh air and sunshine was healthy exercise for them. Sometimes a patient had an epileptic seizure while on the walk. The only option was to stop the procession, wait until the seizure ran its course, and then continue.

The long workdays left little time for leisure activities. On days when I did not work, I went occasionally to Providence. The transportation I used was a motorcycle owned by Herman Lautzenheiser, a Methodist CO from Ohio. He was rather slow and deliberate and had acquired the nickname, “Lightning.” A good-natured fellow, he permitted other people to use his cycle. As a matter of fact, I acquired Rhode Island motorcycle license.

On one occasion, returning to the institution on the cycle, I did not fare very well. A macadam road led from the highway, past the dairy farm, and then to the main buildings of the institution. As I turned off the highway on to the road leading past the dairy farm, I was unaware that the dairy herd was being driven to pasture. There were a number of curves in the road, and upon rounding one curve I came upon the cattle. I steered the cycle toward an opening in the herd, but when I got there the opening had closed. The cycle hit a cow and upset at the side of the road as I tumbled over the handlebars. I was not seriously injured. The cycle was damaged and the cow received a cut. There certainly should have been someone with a warning flag near the entrance to the road.

In May 1994, an Exeter reunion was held in Lancaster County. Herman Lautzenheiser was present. I told him about my experience with his motorcycle, but he did not remember the incident. Herman still owned the motorcycle and recently had it restored.

While in Rhode Island, I had the opportunity to enjoy two excellent programs in Providence. One was Phil Spitalny and the All Girl Orchestra with Evelyn and her magic violin, and the other was a stage production of William Shakespeare’s play, As You Like It, starring Katharine Hepburn.

World War II ended in 1945, and by 1946 men were being discharged and CPS units closed. I was transferred to CPS Unit No. 85 at Howard, Rhode Island, for the last month of service. This unit was located at the Rhode Island State Hospital for Mental Diseases. I was employed as an orderly.

Strange as it may seem, I did not go home immediately upon completing my stint in CPS in October. World Series fever was in the air, and I was excited about the contest between the Boston Red Sox, American League Champions, and the St. Louis Cardinals, National League Champions. It was not possible for me to attend any games in Boston, so I listened to the games on the radio.

St. Louis had won the hard way, coming from a number of games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers toward the end of the season, going ahead by a few games, only to settle for a tie at the end of the regular season. In the playoff between the Cardinals and the “Bums,” the Cardinals won twice by the scores of 4-2 and 8-4.

The “experts” predicted the World Series would not be a contest. Two pygmy teams had fought it out to see who would face the giant. The Cardinals were 7 to 20 underdogs; they would not be able to defeat Ted Williams and Company. A sweep was likely.

How mistaken the “experts” were! Boston won the first game 3-2 in 10 innings. The next two games were shutouts, St. Louis winning game two 3-0, and Boston winning game three 4-0. In game four the Cardinals clobbered the Red Sox 12-3. Boston won game five 6-3, and St. Louis tied the Series at three games each with a 4-1 win in game six. In a thriller, the Cardinals won the World Series with a 4-3 win in game seven. The hero of the Series was Harry “The Cat” Brecheen. He won games two and six as a starter and came on in relief in game seven and was the winning pitcher. He was the first southpaw to win three games in a World Series.

After 21 months of service, I was discharged on October 15, 1946. After the World Series, I began my journey home by train, happy that the Cardinals were Major League Champions.

Concluding observations

Fifty-three years have passed since I entered Civilian Public Service, and some observations are in order. The Selective Training and Service Act, introduced in the Senate as the Burke-Wadsworth Bill on June 20, 1940, became law on September 16, 1940. Section 5 (G) of the Act contained a provision for those “conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form.” They were to “be assigned to work of national importance under civilian direction.” Work of national importance was not defined, and the tasks assigned to CPS men frustrated many of them. How was one to define work of national importance? Was it work· that contributed to the war effort? If so, many would have refused to perform it. Was it work that if not performed would contribute to the weakening of the nation?

In my own case, most of the work I did was not too important, at least from a national standpoint. Whether Farmer Brown in Virginia had a fence had little significance for the nation. It could be argued that fighting forest fires was more important, for if not contained, vast areas of timber would have been destroyed. Behind-the-scenes jobs are important, but doing laundry, waiting on tables, and serving as a cook were not that important from the standpoint of the requirement of the law, unless these tasks supported those whose work was of national importance. The most significant work that I performed was in the hospitals in Rhode Island, but was that work of national importance?

To a degree, CPS was a waste of talent. There were those who had technical and vocational skills. Some campers had undergraduate and graduate degrees. There were limited opportunities for men to use these skills and the academic training they had. Some would have volunteered for more significant and productive assignments.

Patriotism during the war was probably greater than at any other period in our history. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor galvanized the will of the nation as no other event could have. Conscientious objectors were a “thorn in the flesh” to the government, and the best CO was an out-of-sight CO. There was a minimum of contact with the general public. Some CPS men experienced hostility, but I did not. There were veterans working at the Exeter unit in Rhode Island, and although they did not agree with the CO position, they showed respect.

CPS camps were not filled by “good” Church of the Brethren, Brethren in Christ, Mennonites, and Quakers only. Melvin Gingrich, in his book, Service for Peace, lists 87 denominations that had three or more members in CPS. In addition to religious objectors, there were philosophical objectors and probably just plain objectors. Not all were as dedicated and hardworking as the farm-bred Brethren in Christ and Mennonite young men. I recall an incident involving a member of the Russian Molokan denomination. At one mealtime at North Fork, while I was working in the kitchen, this Molokan came into the dining room and filled his plate with the food that was being served for that particular meal. He was very unhappy with the food and hurled the plate with its contents across the dining room and angrily went out the door. It takes all kinds to make a world!

Considering the political climate, propaganda, and patriotic fervor, I suppose the Civilian Public Service program was the best that could be had at the time. Up to this point in my life, I had not ventured far from home, and CPS was definitely an educational and horizonbroadening experience. As I look back, I have mixed feelings. What sacrifice did I make? Yes, I gave 21 months of time without remuneration. Money was paid into a fund by those for whom work was done, but the government never released this money to those who served. When the issue of wages was raised by those negotiating with the government, it was always bypassed. It appears the government thought there would be less opposition to CPS if the men served without pay.

While we were kept out of sight in large measure, and with little opportunity to make a significant contribution, thousands of young men were putting their lives on the line. During my sabbatical trip to Europe in 1980, I visited the American Military Cemetery in Luxembourg where many of those who were killed in the Battle of the Bulge, the last great battle in the European theater, lie buried. A gentle, rolling carpet of beautiful green stretched before me. Hundreds of white crosses in perfect geometrical formation marked the sites of those who gave their “last full measure of devotion.” Their commander, General George Patton, at his request, lies with them. I have the most profound respect for the memory of those who rest there, and for those who rest in countless other sites around the world.

Thanks for sharing your story.

Imagine my surprise to see my parents mentioned in you article. It is some what ironic that years later I reported to Upland College to perform my 1-W service, until they closed. A bonus was meeting my future wife Leanna Book during that time while singing in the Upland Church choir.