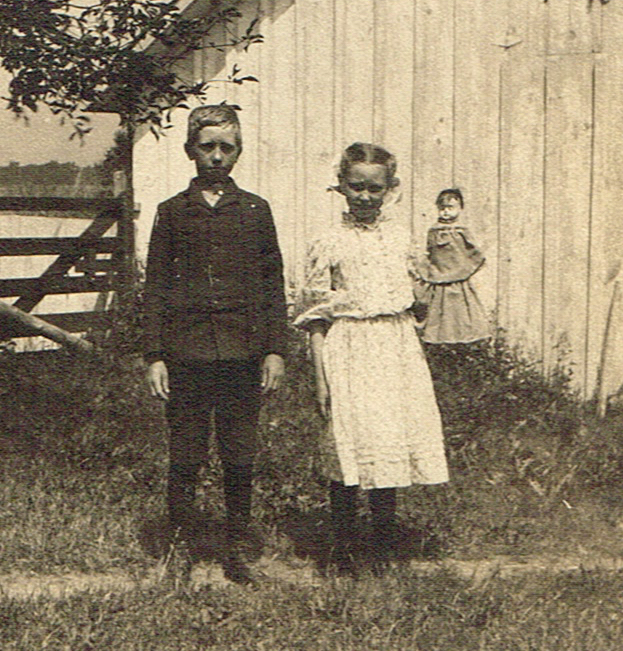

Ernest John Swalm was born in 1897 on a farm in Duntroon, Ontario, about 60 miles north of Toronto. His father, Isaac, was a Brethren in Christ pastor and bishop. His mother, Alice Sammons, was Mennonite Brethren prior to her marriage to Isaac.Ernest grew up with the teaching of nonresistance and, as a young man, embraced it for his own. (In his adult life he was best known as “E. J.”1

A call to war

In 1917, during World War I, the Canadian Military Service Act was passed, creating a military draft. At that time, with advocacy from historic peace church representatives,2 conscientious objectors who were members of such churches were given exemptions from the draft. However, in 1918, when thousands more soldiers were needed to support the war effort, exemptions for conscientious objectors were removed, with no exceptions.3

Very soon after, E. J., age 20, received his draft notification from the Canadian Army. His orders were to report to the army barracks in Hamilton, Ontario, on May 7—just one week away. He was the first Brethren in Christ man in Canada to be drafted. At that time, in Canada, the denomination was known as “Tunker.” Unfortunately, the Ontario registrar “wrongly ruled that Tunkers . . . were not exempted, thereby exposing Tunker men to military discipline for remaining faithful to their beliefs.” Upon hearing of E. J.’s experience, historic peace churches, such as Mennonites, and other non-historic peace churches, such as Seventh-Day Adventists and, Christadelphians, feared that their young men would face the same consequences.4

E. J. and his family experienced anxiety about what lay ahead. He and his father had read a newspaper report that described conscientious objectors who were maltreated by unauthorized men in the army. Some were held under a cold-water pump in the winter which resulted in their deaths from exposure. The next morning, Isaac took the morning train to seek current information that might be of help to E. J. He contacted Mennonite Bishop, Samuel F. (S. F.) Coffman and Brethren in Christ minister, David W. (D. W.) Heise.5 He was aware that Coffman and Heise, along with the Non-resistant Relief Organization, were working to achieve exemptions from military service for conscientious objectors. Specifically, they were now working hard on E. J.’s case.6 Representatives of the organization had already been to Ottawa to meet with government leaders about giving exemptions to Mennonite and Brethren in Christ draftees. However, in Isaac’s discussions with Coffman and Heise, he learned that despite their constant efforts, there was currently nothing that could be done for E. J.

One morning, while doing the chores in the barn, Isaac asked his son, “Suppose the worse comes to worst. How is it with your soul?” E. J. assured Isaac of his strong faith and determination to keep to his convictions. Isaac put his arm around E. J. and, as he wept, said:

I would far rather get word that you were shot—that I should never see you again after you leave home—than to have you come home again, knowing that you compromised and failed to live up to the convictions that you had. Though it would be very hard for me to lose my son, and it would mean a lot, I’d rather know that you honored your convictions if it cost you your life, and I must spend the rest of my days without you.

After a time of prayer in the granary, E. J. came to peace about his decision to stand for his beliefs. In the days before his departure, E. J. gave his possessions to various loved ones. When he left home, he did not expect to return.

Upon arrival at the Hamilton barracks and reporting to his battalion, E. J. expected to take his stand as a conscientious objector (CO) right away. However, as E. J. described, “In this [I was] disappointed as [I] was ushered into army routine and life so gradually and so slowly, that it became a question to decide just when and where [I] ought to take [my] stand.”7 After attempting to make his declaration to three different officers over the first few days, he was eventually referred to Major Bennett, to whom he declared his nonresistant position. Bennett offered E. J. a role as a noncombatant, which he refused. The major told him there were no other conscientious objectors in the battalion. He then threatened that E. J. would be “put in chains, taken overseas and placed in the front lines as a barricade and would be shot . . . with all the other cowards and despicable characters. . . .” E. J. responded, “Be that as it may. By the grace of God I am determined in my stand, and I will not take [military] service, because I intend to be a conscientious objector.”

E. J.’s father visited him the next day. He had been to see Bishop S. F. Coffman who was continuing to intercede with the government on E. J.’s behalf. It was Coffman’s belief that because E. J. was the first Brethren in Christ (Tunker) man to be drafted, the army was making a test case of him. To emphasize his determination, Coffman “said he would follow this case to the Privy Council in England, before he would be defeated.”

In a few days, E. J. was ordered to appear at the quartermaster’s to receive his army uniform and kit, which he immediately refused to accept. The quartermaster responded with threatening and obscene language. A corporal carried E. J.’s uniform and kit and escorted him to the bunk house where he was ordered to put on the uniform. Again, E. J. refused. He was stripped of his civilian clothes after which an army fatigue suit was put on him. He was immediately arrested and taken to the guard house where, to his surprise and delight, he met eight other Christian conscientious objectors, representing various Protestant denominations.

The next morning E. J. and two other “objectors” were taken to Colonel Belson for a preliminary hearing. Belson declared he “would shoot every one of them if he had the authority.” He continued, “I suppose you have some Scripture for that [position].” E. J. replied that he “considered Saul of Tarsus, as he held the clothes of those [who] stoned Stephen [to be] a non-combatant. We don’t read that he threw any stones but he was thoroughly guilty of the crime because he was consenting unto his death.” E. J. continued, “For this reason, [I] could not take any part of it, whether it be stretcher bearer, whether it be making munitions, or what. [I] would just be releasing another man to shoot the bullets and to take life.” The colonel responded by remanding E. J. and the other two men for a district court-martial, to take place in a month.

In a few weeks, the battalion, including the conscientious objectors, was moved to Camp Niagara in the town of Niagara-on-the-Lake. There the COs experienced many threats and much taunting. At one point some soldiers said that arrangements had been made to have E. J. shot. To confirm this, the same soldiers took a paper from a file and read out loud (falsely) that ammunition had been purchased for his execution. When this came to the attention of a Sergeant Hartley, the men involved were stopped. E. J. noted that Hartley and some of the other officers “were some of the finest gentlemen” he had ever met.

The day of the court-martial came.While waiting outside of the court-martial tent, E.J. experienced a period of high anxiety. He prayed that his thoughts of despair would be taken from him. When he looked up, he saw Elder D. W. Heise from Gormley, Ontario (north of Toronto), walking toward him. Heise said that he had read about the upcoming court-martial in the Toronto Globethe previous day. Knowing that Isaac Swalm couldn’t be present, Heise left home at three o’clock in the morning, walked three miles to Toronto and took the first boat to Niagara-on-the Lake, arriving just five minutes before the court-martial. E. J. was overwhelmed by Heise’s kindness and support. Heise accompanied him into the tent, where E. J. was tried as a conscientious objector, as a defaulter, and for disobeying a lawful command given by a superior officer (refusing to put on uniform when ordered). He pled guilty. Heise was allowed to testify to E. J.’s character, but to no avail. All nine COs were charged with the same crime and all were sentenced to two years hard labor.

Three days later the COs who had been court-martialed were taken to a field where the battalion was lined up in a square formation. The COs were paraded in. As each man’s sentence was read, the sergeant-major removed the man’s cap and shoved him two paces forward. E. J. believed that the public reading of their sentences was “intended to intimidate us and warn the onlookers.”

Just prior to leaving the camp, the COs sang several hymns outside the guard house. So many soldiers gathered to listen that “military police stood in between the [COs] and the [soldiers].” E. J. noted that “[S]cores of deeply-moved soldiers wept out of sympathy for [the COs] and because of the spiritual impact gospel singing creates on human hearts.” The men were then transported to the county jail in St. Catharines to await the arrival of the provincial sheriff who would take them to the federal prison in Kingston, Ontario.

Upon arriving at the jail, they received unexpected kindness. The governor of the jail, Mr. Bush, was sympathetic to them and expressed regret that they needed to be jailed. In fact, Bush’s grandfather had been a Tunker preacher. In addition, Bishop S. F. Coffman was a personal friend of Bush’s. (Coffman lived nearby and visited E. J. several times during his time in jail.) The men were also happy to find 18 more conscientious objectors in the jail. Further, each of the COs were in cells in the same block, enabling them to worship, study the Bible, and sing hymns together in the large hallway.

On the negative side, Garley Clinch, their 70-year-old guard, was hostile and mean towards the COs for their nonresistant stance and their Christian faith. Besides being verbally abusive, he stopped them from singing hymns when he was present and became angry when they prayed. The COs decided to privately pray for Clinch. Over the weeks, Clinch warmed to them, asking them to sing hymns, and to answer questions about the Bible. Sometime later, with the guidance of one of the COs, Clinch committed his life to Christ.

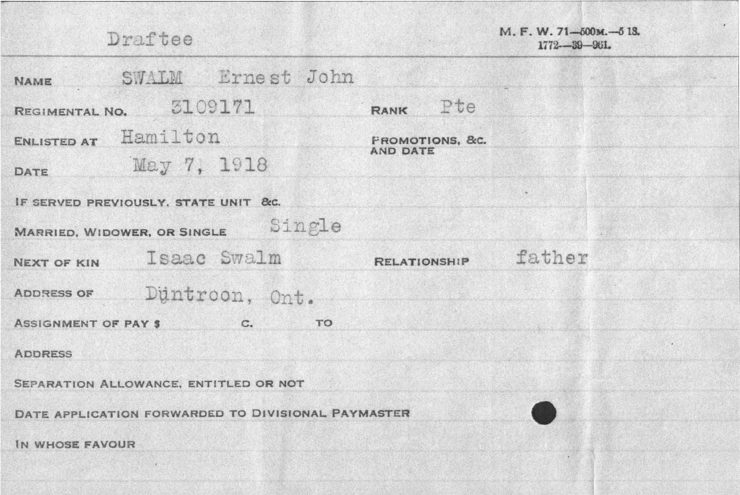

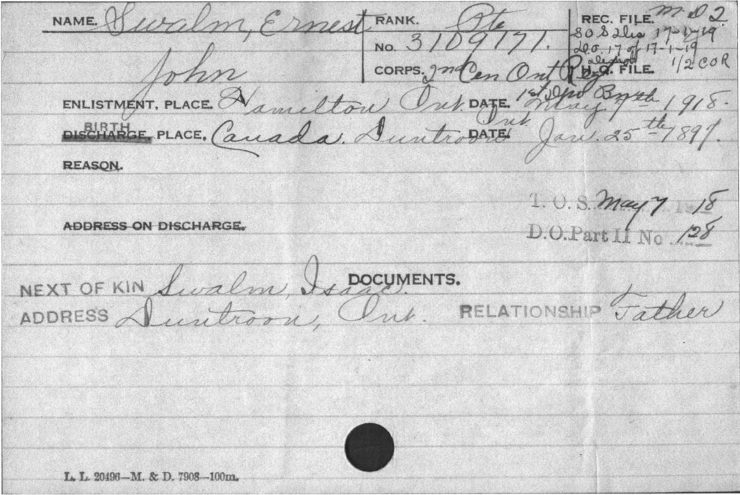

Thanks to the tireless efforts of S. F. Coffman and D. W. Heise, after four weeks in the St. Catharines jail, E. J. was paroled and told to report to military headquarters once a month.8 When the war ended four months later, E. J. was shocked to find that he had been honorably discharged. There are no references to conscientious objector status in E. J.’s draft or discharge papers.

Impact on E. J. Swalm’s life

Looking back on E. J.’s life, it is clear that his World War I experience deeply impacted the future direction of his life.He himself said, “This unique experience to a great extent set the course for my life.”9 Along with becoming a Brethren in Christ pastor, a bishop, and a sought-after evangelist, he felt compelled to educate current and future generations about the “peace position” of the Brethren in Christ. To prepare himself, he earnestly studied the biblical doctrine of peace. E. J. also developed his public speaking skills; M. J. Heisey describes him as a “powerful orator and storyteller. . . .”10 His signature humor added to his appeal. E. J. drew large crowds when he told the story of his World War I experience and preached on nonresistance in Brethren in Christ and Mennonite churches, in multi-denominational peace conferences, in non-peace churches, and in other settings. Howard Landis, one of Heisey’s questionnaire respondents, noted that one of the reasons Brethren in Christ churches in Pennsylvania were “packed out” was that “many Church of the Brethren and Mennonites [also] came to hear of Ernie’s pilgrimage relative to his stand in World War I.11 As of 1976, E. J. had publicly shared his story over 250 times.12 He also counseled draft-age men and teenage boys in small group settings and individually.

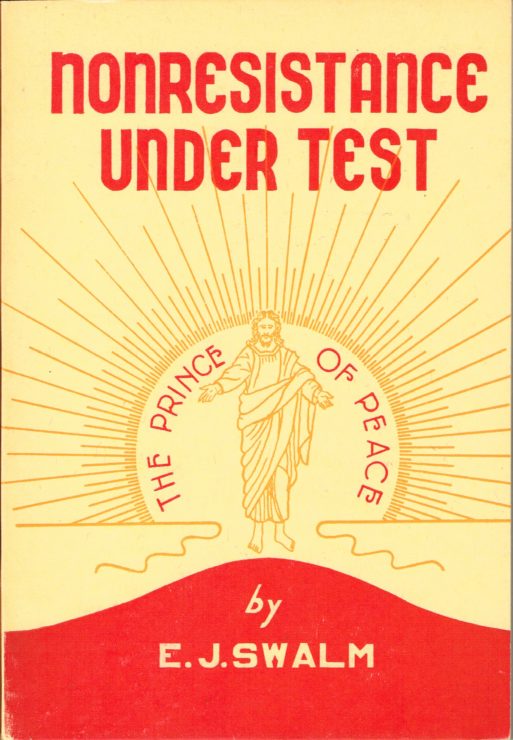

In 1938, E. J.’s talk was published as a small book titled, Nonresistance Under Test. By the early 1950s, over 8,000 copies had been printed. The book was owned by many Brethren in Christ families and was read by hundreds, possibly thousands, of teenagers and adults.13

E. J. was also active in Brethren in Christ General Conference committees related to peace, such as the Peace, Relief, and Service Committee; and in Canadian Conference committees, such as the Ontario Brethren in Christ Nonresistance Committee. The latter was formed in 1938 by the General Conference and, like a similar American committee, was commissioned to contact government authorities to remind them of the denomination’s historic doctrine of nonresistance to war. The Committee was also authorized by the Canadian Brethren in Christ Joint Council, “to work with other non-resistant bodies in Canada in presenting their views.”14 E. J. was uniquely prepared to work with other nonresistant denominations. As previously noted, as a result of his World War I experience, E. J. was introduced early on to Mennonite leaders such as S. F. Coffman, and others. He had maintained these contacts.

With communication channels officially opened, especially between the Mennonites and Brethren in Christ, the need for historic peace churches to be proactive with the Canadian government became urgent, at least to some. As Samuel J. Steiner notes, although they respected the older NRRO leaders, E. J. and other younger Mennonite leaders became impatient with S. F. Coffman and his peers who were assuming that the government would continue to provide exemptions for their young men during World War II as it had during World War I. E. J. decided to take some action. Under the auspices of the Brethren in Christ Nonresistance Committee, he was “the primary instigator” in inviting various groups of Ontario Mennonites from similar peace committees, to address the issue of compulsory military service. Out of this well-attended meeting, the Conference of Historic Peace Churches (CHPC) was formed; E. J. was elected as its chair. Following the initial meeting, the Society of Friends (Quakers) was approached, and subsequently joined CHPC.15

CHPC was an organization of historic peace churches that was deeply involved in meeting with the Canadian government during World War II, advocating for conscientious objector status and proposing alternative service options16 It should be noted that CHPC leaders, including E. J., were frequently “called upon to speak on behalf of COs who were not members of historic peace churches as the government preferred to relate to one group on the issue.”17

During the war, CHPC established a subcommittee, the Committee on Military Problems (CMP) which communicated directly with the federal government. It also dealt with practical issues and cases of individual COs. E. J. was part of this committee which traveled an average of two to three times a week to Ottawa, Ontario (the capital of Canada) to meet with government representatives, and at least once, with the prime minister. Following a number of intense meetings, the peace church representatives successfully negotiated exemptions for conscientious objectors who were members of historic peace churches.18

Although the CHPC members were very pleased to gain exemptions for their church members, they also wanted to contribute to their country. E. J. described it this way: “We stated [to government officials] that we were not satisfied to take a negative position, but wished to make some positive contribution to the country’s welfare, provided this could take the form of constructive civilian work under civilian control.”19 In May 1941, the government, at the suggestion of the CMP, was at last persuaded to set up an Alternative Service Workers program similar to the Civilian Public Service program in the United States. Draftees from historic peace churches (and other approved conscientious objectors) were allowed to do their alternative service at Alternative Service camps.20 Unlike American Civilian Public Service Camps, which were funded by denominations, Canadian camps were run by the government21

Serving in remote Alternative Service camps could be discouraging for COs22) CHPC tried to have a religious director on staff at each camp but there were many men and just one director. To further encourage the COs, E. J. and many Brethren in Christ and Mennonite pastors and church leaders visited the men in the camps. (E. J. also visited American COs. He reported that during one six-week period, he traveled about 8,000 miles to visit CPS camps and hospital units.)23)

The Northern Beaconnewsletter, produced by men at the Canadian Montreal River Alternative Service Work Camp, describes one of E. J.’s 1942 visits, during which he spent several days teaching, encouraging, and talking informally with the men in the camp. The writer notes that in one service, “Bishop Swalm told us of his life as a Conchie during the last World War.”24 The men appreciated visitors from church leaders. Bruce Nix, one of the COs at Montreal River Camp, said, “E. J. Swalm and J. Harold Sherk [did] so much for us boys. We could never repay them for their untiring work, traveling to Ottawa and Toronto and up to the camp and ministering to all the boys.”25

Of interest was a non-peace church visitor to the camp, United Church of Canada pastor R. Edis Fairbairn. In addressing the camp men Fairbairn said, “I deeply regret that my own church turned up its official nose at the request that it find or make suitable opportunity for such service for its conscientious objectors.”26 In all, although the majority of COs at the Montreal River camp were Mennonites, including the Brethren in Christ men, there were more than 10 other denominations represented as well.27 E. J. had a high regard for non-church affiliated COs and COs who were not part of an historic peace church whom he met in the camps and when imprisoned during World War I.28

Swalm family support ((Material for this section was taken from:Beth Hostetler Mark and Louann Swalm Walker, “Maggie Steckley Swalm: A Teacher of Good Things,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 28, no. 3 (December 2005): 432; Beth Hostetler Mark, “Paul and Lela Swalm Hostetler,” in Worthy of the Calling: Biographies of Paul and Lela Swalm Hostetler, Harvey and Erma Heise Sider, Luke Jr. and Doris Bowman Keefer, ed. E. Morris Sider (Mechanicsburg, PA: Brethren in Christ Historical Society, 2014), 23-24; and Ray Swalm, “Legacy of E. J. Swalm: A Response to the Legacy of E. J. Swalm,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 42, no. 1 (April 1993): 76-77.))

E. J., like many of the other CHPC members, relied on income from the farm. However, given that he spent about 75 percent of his time doing peace work during the war years, it became impossible for him to fulfill his obligations for running the one hundred-acre farm. For a while his wife, Maggie, with the help of their hired man, John Patfield, ran the farm in E. J.’s absence. However, there came a time when John was drafted and no other men were available for hire. When their oldest daughter Lela graduated from high school, she began to help her mother with the farm work. Maggie and Lela did the bulk of the chores: feeding the animals, cleaning out the stables, milking and processing the milk, grinding grain, and birthing calves. Siblings Milly and Ray helped with daily chores when they were not in school. In the summer, Lela and Milly (then a young teenager) plowed fields and one year, roofed a tall barn. Another sister, Jean, helped with household chores.

During the war years, Lela drove E. J. back and forth on his many trips to Kitchener, Ontario, in connection with CHPC business. She also typed his correspondence and notes. At the end of the war, six years after her high school graduation, Lela fulfilled her dream of attending Messiah College in Pennsylvania.

Despite his many absences, E. J. was a loving, and loved, husband and father. His children were all very proud of his accomplishments.29 They were well aware, however, that it was Maggie’s support and hard work that made E. J.’s success possible.30 To E. J.’s credit, he not only expressed his deep appreciation to Maggie, Lela, Milly, and Ray in person and in letters; he also spoke about it publicly. In My Beloved Brethren, he recognized Maggie, noting that “My devoted companion paid the larger share in many ways. Her bravery, efficiency, and fortitude of spirit contributed immeasurabl[y] to my work.”31

Legacy of E. J. Swalm

Besides the many offices he held, and the numerous (over 7,000) sermons he preached, E. J. had a lasting influence on young men and women, especially the generation that followed his. In the Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, the authors wrote about E. J.: “His greatest legacy lies in the generations of Brethren Christ people who credit him as an important influence on their decision to choose the Christian way of peace.”32

In 1996, M. J. Heisey sent a questionnaire (referenced previously), “Questionnaire on Brethren in Christ Nonresistance,” to a sampling of Brethren in Christ men and women, most of whom were teenagers or young adults during World War II. Almost half of those who completed the questions about nonresistance mentioned E. J. Swalm. Many commented on having heard him speak and having read Nonresistance Under Test. Heisey observed, “Above all, people associate nonresistance with E. J. (“Ernie”) Swalm’s story of his World War I experiences as a conscientious objector.”33 Several respondents commented on his influence on their lives. Ray Zercher stated, “I am sure I would not have chosen the CO position except for the influence of C.N. Hostetter and E.J. Swalm.”34 On a lighter note, Elsie Bechtel wrote, “To us, he seemed like a hero.”

E. J. was a founding member of Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) Canada, a peace, relief, and service agency of the Mennonites and Brethren in Christ. Lucille Marr, in her book about the MCC in Ontario notes that E. J.’s stories “inspired his contemporaries and a new generation of Brethren in Christ and Mennonite youth. [Many of them] link their life-long commitment to Mennonite Central Committee to Swalm’s ministry and example.35

Remembered by scholars

There has been a resurgence of interest in various aspects of conscientious objection during World Wars I and II, as well as in Mennonite histories of various kinds. Numerous scholarly books and journal articles on such topics include references to E. J36 In 1977, as a result of a recommendation from Frank Epp, a Mennonite scholar and president of Conrad Grebel College, E. J. was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Laws by the University of Waterloo. The degree was given to coincide with the inauguration of Conrad Grebel College’s Peace and Conflict Studies program.37 This was a great honor to a man who was self-educated and well-spoken, but who left school after eighth grade to work on the family farm.38

Later years

In 1967, E. J. retired as bishop of the Brethren in Christ Canadian Conference and resigned from all major committees and organizations. However, he continued to preach and tell his story, and to influence young people. In 1970, a group of Messiah College students entered a float in the homecoming parade. It visually told E. J.’s World War I story.

During the Vietnam War, at the age of 74, E. J. spoke in a Messiah College student chapel service about his World War I story and the biblical basis for the peace position. There was great interest in his talk. Afterward, he met with students in question and answer sessions. Nancy Heisey, one of the Brethren in Christ students from this time reflects, “In my frame of reference, he was a kind of icon, so just his presence, his plain suit, and the fact that he had such a story, were what impacted me.”39

E. J.’s granddaughters, Beth and Karen Hostetler, were also students at the time and, along with other students, had been participating in anti-war activism. E. J. was proud that they had taken the Brethren in Christ beliefs in pacifism and nonresistance to heart. Beth’s future husband, Ken Mark, was a United Methodist. He was so deeply impacted by E. J.’s talks that he joined the Brethren in Christ Church and applied for conscientious objector status, which he was granted. E. J. was pleased to be a reader for the paper Ken wrote as part of his application.40 Engaging with younger generations was a goal of E. J.’s. He believed that “nonresistance must be intelligently reinterpreted each generation.”41

For two more decades, E. J. continued to share his story. Pastors, young people, researchers, and others sought him out for counsel on peace and other issues and to hear his stories. These visits sometimes involved a day’s travel (or more) to the Swalm farm.

At the age of 93, E. J. was interviewed for a video, A Different Path.In it he reflected: “To me, this business of being a Christian is a lifetime job. . . . You have to decide: ‘Shall I or shall I not do some things?’ And with that [you] must have the courage, when you know what is right, to do it.42

- Unless otherwise noted, the re-telling of E. J. Swalm’s World War I story comes from two sources: E. J. Swalm, “My Beloved Brethren …”: Personal Memoirs and Recollections of the Canadian Brethren in Christ Church (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1969) and Swalm, Nonresistance Under Test: The Experiences of a Conscientious Objector, As Encountered in the Late World War by the Author(Nappanee, IN: E. V. Publishing House, 1938). Specific citations will not be given. [↩]

- Melvin Gingerich and Paul Peachey, “Historic Peace Churches,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online,1989, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Historic_peace_churches&oldid=88064: “Historic Peace Churches” is a term widely used for the three denominations which have for centuries held the position that the New Testamentforbids Christian participation in war and violence. These three are the Brethren, the [Society of] Friends (Quakers), and the Mennonites. The term came into common usage in America between World Wars I and II.” Brethren in Christ (Tunkers in Canada) came to be under this umbrella. [↩]

- Thomas P. Socknat, Witness Against War: Pacifism in Canada, 1900-1945(Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 75-79. [↩]

- Socknat, Witness Against War, 76. [↩]

- . F. Coffman and D. W. Heise were the key representatives for their denominations in interactions with Canadian government officials. For Coffman, see Samuel J. Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands: A Religious History of Mennonites in Ontario(Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press, 2015), 207. For Heise, see Swalm, My Beloved Brethren, 54. Swalm noted that Heise “was considered the most able to represent the interests of the [Brethren in Christ] Church before the Canadian Government.” [↩]

- The original spelling was “Non-resistant;” the spelling later changed to “Nonresistant.” S. F. Coffman, “Nonresistant Relief Organization (NRRO),”Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, 1953,http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Nonresistant_Relief_Organization_(NRRO)&oldid=135601: The NRRO was formed in 1917 to raise money for the Canadian government to relieve war suffering and to support efforts to achieve exemptions for conscientious objectors. [↩]

- n Nonresistance Under Test, E. J. sometimes used the plural pronouns “we” and “our” when referring only to himself. This is a dated usage sometimes referred to as the “royal we.” Throughout, when using exact quotations, I have changed that usage to the more common first person use of “I” or “my,” using square brackets to indicate the change. [↩]

- In a letter to Isaac Swalm, Heise noted that he was “on the go almost night and day this week on behalf of our boys. . . .”: Swalm, My Beloved Brethren, 43. Coffman was similarly busy on behalf of the COs. In the early 1970s, John Weber, who interviewed E. J. Swalm regarding S. F. Coffman, said that E. J. emphasized that Coffman personally worked to get him exempted from military service: John Weber, conversation with the author, August 30, 2018. [↩]

- E. J. Swalm,source unknown, quoted inRonald J. R. Mathies, “The Legacy of E. J. Swalm: As a Churchman in the Wider Christian Community in the Witness of Peace,” Brethren in Christ History and Life41, no. 1 (April 1993): 60-61. [↩]

- M. J. Heisey, Peace and Persistence: Tracing the Brethren in Christ Peace Witness through Three Generations(Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2003), 14.For an analysis of E. J.’s oratory, see, “Lester C. Fretz, “The Legacy of E. J. Swalm: His Oratory and Humor,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 41, no. 1 (April 1993): 67-71. [↩]

- sey Papers, Box 1, MG-138, Brethren in Christ Historical Library and Archives, Mechanicsburg, PA. Hereafter, referred to as Heisey Questionnaires. A copy of the questionnaire, “Questionnaire on Brethren in Christ Nonresistance: World War I through the Early 1950s” can be found in Heisey, Peace and Persistence, 169-170. Regarding talks at non-peace churches, the author recently discovered a handwritten sermon outline that was used to speak to such a church. In it E. J. begins his talk by making clear that he is respectful of the beliefs of others. He also notes that he had met military men who were “some of the finest Christians” he knew: E. J. Swalm Papers, Brethren in Christ Historical Library and Archives. [↩]

- ’War Lecture’ Given 250 Times,” Collingwood Enterprise-Bulletin, August 11, 1976. [↩]

- Heisey, Peace and Persistence, 50; A significant number of Heisey’s questionnaire respondents mentioned having read the book. Morris Sherk, one of the respondents, stated: “I heard him relate his experiences and many Brethren in Christ homes had his book Nonresistance Under Test.” In addition, E. J.’s book would have been purchased by many of the Mennonites and others he spoke to. [↩]

- E. Morris Sider, The Brethren in Christ in Canada: Two Hundred Years of Tradition and Change (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1988), 231. [↩]

- Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands, 300-304. [↩]

- Steiner,302-304. For more about CHPC, see:Harold S. Bender, “Conference of Historic Peace Churches,” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, 1955, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Conference_of_Historic_Peace_Churches. When fully formed, CHPC was comprised of the following denominations: Brethren in Christ, Mennonite Brethren in Christ (now Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada), Old Order Mennonite, Amish Mennonite, Society of Friends, Brethren, Old Order Dunkard, and the Ontario sections of the Mennonite Brethren and General Conference Mennonites. However, the leadership was usually comprised of Brethren in Christ, Mennonites, and Society of Friends. E. J. Swalm served as CHPC chair from 1940-1964. [↩]

- “’War Lecture.’” [↩]

- Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands, 305-310. [↩]

- Carlton O. Wittlinger, Quest for Piety and Obedience: The Story of the Brethren in Christ (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978), 378-379. [↩]

- Socknat, Witness Against War, 236-237. For more information about the Alternative Service work camps, see Melvin Gingerich, “Alternative Service Work Camps (Canada),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, March 2009, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Alternative_Service_Work_Camps_(Canada). [↩]

- Socknat, Witness Against War, 237. [↩]

- “’War Lecture.’” (2 [↩]

- Mathies, “Legacy,” 57. (2 [↩]

- “Bishop E. J. Swalm Pays Official Visit,” The Northern Beacon, March 7, 1942, 1,https://uwaterloo.ca/grebel/sites/ca.grebel/files/uploads/files/northern_beacon_v1n3.pdf. [↩]

- Heisey Questionnaires. J. Harold Sherk was a Mennonite pastor, educator, and peace worker who not only visited the camps; he spent time as spiritual director at the Montreal River camp. He was also secretary of CHPC for four years: Lucille Marr, “Sherk, J. Harold (1903-1974), Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, July 2013, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Sherk,_J._Harold_(1903-1974). [↩]

- R. Edis Fairbairn, “Guests of Montreal River Camp,” The Northern Beacon, May 1942, 1, https://uwaterloo.ca/grebel/sites/ca.grebel/files/uploads/files/northern_beacon_v1n7.pdf. [↩]

- Steiner,In Search of Promised Lands, 314-315. Denominations represented: Brethren in Christ, Mennonite (more than one Mennonite branch), Amish, Old Order Mennonite, Christadelphian, Plymouth Brethren, Jehovah’s Witness, Seventh Day Adventist, Pentecostal, Salvation Army, Society of Friends, United Church of Canada, and other mainline denominations. [↩]

- Swalm,Nonresistance under Test: The Experiences of a Conscientious Objector, as Encountered in the Late World War, 40, 43-44. COs not affiliated with historic peace churches served time doing hard labor: Swalm,“Glimpses from Civilian Public ServiceTours,” in Nonresistance under Test: A Compilation of Experiences of Conscientious Objectors as Encountered in Two World Wars, comp. E. J. Swalm (Nappanee, IN: E. V. Publishing House, 1949), 170. [↩]

- Winnie Swalm, email message to author, October 27, 2018. Winnie notes that Ray Swalm “admired [his father] greatly.” The author recalls hearing similar sentiments in informal conversations with Lela Swalm Hostetler, Jean Swalm, and Mildred Swalm Hawes. [↩]

- Ray Swalm, “Legacy,” 76. [↩]

- My Beloved Brethren, 41-42. [↩]

- Devin C. Manzullo-Thomas and Lucille Marr, “Swalm, Ernest J. (1897-1991),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online,April 2013, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Swalm,_Ernest_J._(1897-1991)&oldid=147312. [↩]

- Heisey, 54. 118 of Heisey’s questionnaire respondents completed the questions about nonresistance; 55 of them mentioned E. J. Swalm. [↩]

- C. N. Hostetter, a former Brethren in Christ bishop and president of Messiah College and close friend of E. J.’s, was a well-known speaker on the peace position as well as a strong advocate for American conscientious objectors: E. Morris Sider, “Hostetter, Christian N., Jr. (1899-1980),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Online Encyclopedia, 1987, https://gameo.org/index.php?title=Hostetter,_Christian_N.,_Jr._(1899-1980). [↩]

- Lucille Marr, The Transforming Power of a Century: Mennonite Central Committee and its Evolution in OntarioKitchener, ON: Pandora Press, 2003), 50. [↩]

- Some of these sources have already been cited: Heisey, Peace and Persistence; Marr, Transforming Power of a Century ; Socknat, Witness Against War; and Steiner, In Search of Promised Lands. A few others are: Laureen Harder-Gissing, “Companions on the ‘Lonely Path’: The Conference of Historic Peace Churches, 1940-1964,” Canadian Journal of Quaker History76 (June 2011): 1-16 and Amy J. Shaw, Crisis of Conscience: Conscientious Objection in Canada During the First World War(Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009). One children’s book has been written about E. J.’s World War I experience: Sandi Hannigan, E. J. Makes Good Choices(Nappanee, IN: Evangel Publishing House, 1998). [↩]

- Mathies, “Legacy,” 61-62. [↩]

- It wasn’t unusual for rural boys of E. J.’s age to end their schooling early. E. J’s father Isaac lost his arm in a farm accident and needed E. J.’s help more than most. [↩]

- Nancy Heisey, email message to author, October 27, 2018. Another student, David Witter, remembered E. J.’s talk, noting that “he validated my beliefs.”: David Witter, email message to author, October 27, 2018. [↩]

- Unless otherwise indicated, information for this section comes from recollections of the author. [↩]

- Heisey, Peace and Persistence, 54. [↩]

- A Different Path : Mennonite Conscientious Objectors in World War II,directed by Nan Cressman (Kitchener, ON: Mennonite Central Committee; Rogers Community 20, 1994), video recording, VHS. [↩]