The joys and merits of research

I love research. Of course, I am aware that not everyone enjoys it as much as I do. I enjoy the reward of finding out the details of people’s lives and the nature of their passions: David Moyo’s political inclinations or Myron Taylor’s compulsion to visit remote places. I enjoy the pleasure of interviewing people: talking with Stephen Muleya about Zambia’s educational history or interviewing David Climenhaga about anything African. I enjoy the puzzles of background research: discovering where Taylor was actually attacked. I enjoy the rigor of bibliographic work: searching for that one source to confirm a theory. I enjoy the challenge of getting good audio recordings: moving that strong voice to the back of the ensemble in order to achieve balance. I enjoy the satisfaction of finding evidence to prove a point: hearing the name “Kuchwa” and knowing for sure I had found the location of the lion attack. I enjoy the realization that my presumed interpretation is wrong: discovering that denominational affinities are actually higher than I expected. Ultimately, I simply enjoy gaining knowledge.

Some thoughts on knowledge

However, like anyone, my love of knowing is shaped and directed by personal preferences and predispositions. First, I am a firm believer in the value of knowledge for its own sake. I do not believe we need a practical reason to justify our pursuit of knowledge. For me, “knowing” is ipso facto a good thing. Additionally, I see knowledge and knowing as nuggets of God’s great wisdom. I take scriptures like Proverbs 10:14 seriously: “The wise store up knowledge, but the mouth of a fool invites ruin.” Of course, as scripture suggests, knowledge alone is inadequate and is not synonymous with wisdom. But without knowledge we can easily be governed by ignorance, swayed by whims of fancy, or blinded by impulses of uncontrolled emotions and ego.

Second, I find local knowledge to be more interesting than universal knowledge, and qualitative interpretation more insightful than quantitative evidence. My thinking in this regard was strongly influenced by reading the work of Clifford Geertz in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I was especially taken by his companion ideas of “local knowledge” and “thick description.”[1] At the time, Geertz’s framework provided a rationale for my desire to examine white gospel music in central Pennsylvania.[2] I was inspired by his method of thick description as a means for finding clues to meaning. In short, Geertz argued that meaningful interpretation ultimately benefits by overly-rich descriptions with lots of detail. He believed that the thick layers of detail thus provided give important clues to those who attempt to interpret the information. Moreover, his emphasis on local knowledge as a primary lens through which one can discover, compare and interpret culture offered me a clear sense of scholarly direction.

Many researchers feel compelled to describe “the big picture,” thinking that “the small picture” is inadequate and uninteresting. By contrast, I find the experiences of regular people in unexceptional circumstances to be enormously interesting and informative. Life at the local level represents a truth that is distinct from the bigger picture. Perhaps this is one reason I liked the sitcom Seinfeld, a television show about “nothing.” It, too, revealed truth about human nature but at a very local level. Increasingly during my time in graduate school, I came to value particularized knowledge over generalized theoretical frameworks.

Clifford Geertz’s and my ideas overlap with the outlook of so-called microhistorians such as Carlo Ginzberg and Edward Muir.[3] Sigurdur Magnusson offered the following succinct description of Ginzberg’s work: “Ginzburg and many of his colleagues attacked large-scale quantitative studies on the grounds that they distorted reality on the individual level. The microhistorians placed their emphasis on small units and how people conducted their lives within them. By reducing the scale of observation, microhistorians argued that they are more likely to reveal the complicated function of individual relationships within every social setting and they stressed its difference from larger norms.”[4]

Both Geertz and the microhistorians agree that we can understand more fully by examining things at the small level rather than the large. The adage that “it is difficult to see the forest for the trees” is relevant to this tread of thought. Like Geertz and microhistorians, I believe we CAN see the forest by looking closely at the trees. Moreover, the experience of the tree, while connected to the experience of the forest, is substantially different and interesting for its own sake. The implication of the tree-forest metaphor is that the “big picture” (i.e. the forest) is inherently more true and more significant than the more-particular viewpoint (i.e. the tree). I think otherwise.

In one reflection on his scholarly work, E. Morris Sider explained some of the advantages of the microhistory approach for those doing historical research on small denominations. Sider described his personal journey from the general to the particular, noting that after completing his graduate studies and having been employed at Messiah College, his focus increasingly shifted to research and writing at the micro level:

I found, somewhat to my surprise, that I now not only had interest but also fulfillment in devoting most of my research and writing time to work on the denomination. In part, it was because I began to realize that no one would be widely excited about another book on Victorian England; in part, it was that I began to feel that I was fulfilling the kind of need for a small church group that I have described above.[5]

Others have expressed similar outlooks. Donald Durnbaugh, a Church of the Brethren historian, echoed many of Sider’s feelings.6] Durnbaugh noted that particularistic histories of denominations written by so-called insiders had gained academic legitimacy in the last quarter of the twentieth century. And Luke Keefer, Jr., in an issue of Brethren in Christ History and Life devoted to the history of the Historical Society’s journal, affirmed the need for and the value of denominational research and writing.[7] The sentiments of these writers ring true for me.

My embrace of thick description, local knowledge, and microhistory is evident in nearly all of my work. Like other ethnomusicologists of my generation, I read Boas’ The Mind of Primitive Man (1911), Durkheim’s Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1915), Weber’s Protestant Ethic (1930), Benedict’s Patterns of Culture (1934), Bateson’s Naven (1936), Malinowski’s Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays (1948), Firth’s Elements of Social Organization (1951), Radcliffe-Brown’s Structure and Function in Primitive Society (1952), Levi-Stauss’s Raw and Cooked, (1969); and others.[8] I greatly appreciated their attempts to create over-arching theoretical frameworks. But, the more-particular ethnographic work of scholars like Edwin W. Smith, who described Zambia’s Ila culture in detail, and Frances Densmore, who documented the music of Native Americans captured my attention.[9] I continue to see the advantages and the value of concentrating on particular subjects, both to understand generalities and merely for the sake of the substance of the particular.

The merits of research

Although I believe all knowledge is worthwhile in and of itself, there are also a variety of practical reasons for maintaining a robust denominational research tradition. The well-worn adage that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” aptly conveys one of the most powerful reasons for us to foster research. We learn from our awareness of the past. Despite the protestations of hyper-pragmatists or anti-intellectual naysayers, it will always be inadequate to merely “live for the present” or “in the present.” Forgetting or ignoring the past is a serious mistake. What follows are a few additional reasons for continued research.

Our research “leaves a record.”

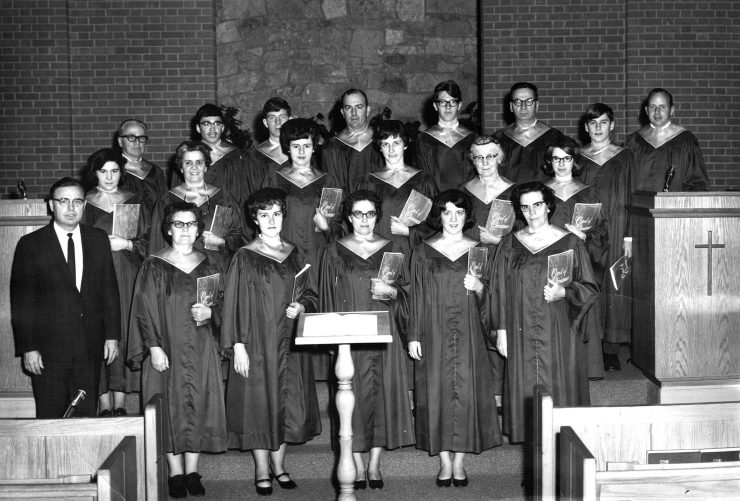

The gaps in our knowledge of the past become especially noticeable when one searches for the past. I cannot count the times I have thought, “I wish someone would have documented this.” Several instances from my book come to mind. For the Brethren in Christ worship essays, for example, finding a photograph of a Brethren in Christ choir or worship service in progress was extremely difficult. Thankfully, we finally found a lovely photo of the Nappanee choir, which includes my father.

However, I have no knowledge of audio recordings of such choirs from the mid-twentieth century. And, surprisingly, I have yet to find an early recording of Brethren in Christ congregational singing.[10]

Another example of knowledge gaps is the unfortunate absence of specific details related to the Brethren in Christ Church in Africa. We frequently find names but often no details about the lives of the early African workers. This is true even for very significant people such as Peter Munsaka or Sampson Mudenda. And information about women is almost non-existent. Rummaging for evidence can be fun (like searching for mushrooms, I suppose), but the setbacks of the research quest are also reminders of how often we fail to record or document events, people, etc.

Our research tells our stories.

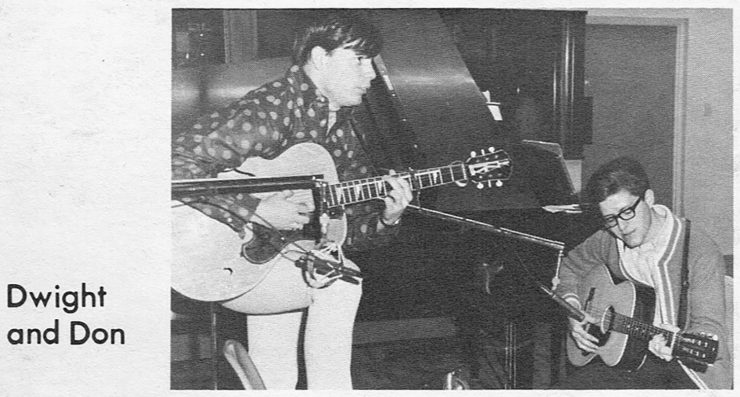

Researching and retelling stories from the past establishes a record of who we are and helps to explain why we are the way we are. My Welsh heritage might explain some of my verbosity and musicality. The experience of Anabaptist persecution might explain some of the cultural traits still found among the plain people. The cultural heritage of Africa might explain the highly oral nature of communication in present-day Black communities. Remembering the earliest Brethren in Christ efforts at contemporary Christian music should remind us that every generation seeks to express itself through its cultural products. I undoubtedly thought my polka dot shirt was hip when this picture was taken, and we certainly believed “In the Stars His Handiwork I See” was “really cool” at the time.

Moreover, telling stories helps to sustain and spread our values. Stories of servant-leaders communicate to others the importance of that paradigm in our understanding of the church. Stories of perseverance in the midst of adversity inculcate those values in our children. Myron Taylor’s dedication to the task of spreading the gospel continues to inspire people almost one hundred years after his death.[11]

Telling our stories also puts things in perspective. Complicated stories help us to understand that issues are rarely black and white. New understandings also shed light on earlier events. For example, our increasing sensitivity to gender inequality illuminates the story of Frances Davidson.[12] Our closeness to a particular moment in time often simply blinds us to its realities. The benefit of time lends perspective to earlier events. For example, a leader’s errors in judgement are much easier to recognize when one is removed by time from the event and the person. Research lends perspective to our experiences.

Our research recognizes the worth of others.

When we interact with others about their experiences, our research acknowledges the value of “the other.” Simply asking questions implies that we are commending them for being “holders of knowledge” related to their own traditions. Expressing pleasure with Tonga renditions of older American hymns validates their musical choices.[13] Recognizing the unique beauty of a particular musical expression such as the slurs used by Old Order River Brethren when singing their hymns, confers legitimacy to an expression which might otherwise be viewed as anachronistic. Taking the effort to document a tradition conveys to others that we value them.

Research can sometimes lead people to re-evaluate their own local traditions and seek to preserve them. This was the case in Zambia at Chikuni Mission Station, where Father Wafer maintained a cultural research center for many years. His work gave birth to a well-attended annual Tonga music festival that continues to encourage the preservation of traditional Tonga music. In the face of overwhelming pressures to Westernize Christian music in India, one could wish for a similar result with the beautiful tradition of Santal tunes.[14] With the increasingly pervasive influence of television in Africa, one might hope that some might see the value of preserving the African oral tradition of story-telling. And, with the advent of amplified instruments among the Zambian Brethren in Christ, I pray that their tradition of congregational singing will not suffer.[15]

Whether our research efforts lead to preservation or not, my experience has been that showing interest in people nurtures both individual and corporate self-confidence. Expressing our curiosity about people’s activities and their products generally confers a degree of approval, which results in feelings of pleasure and self-confidence. Reactions to my questions frequently seem to be saying, “Oh? You really like our music?” Simply taking time to talk with people about their lives seems to convey an appreciation for who they are, which translates into self-confidence. Morris Sider noted this in his essay:

A second advantage of writing the history of small groups is the value it holds for the group. Small as well as large groups need to know who they are, need a sense of identity and, for some, like my own group, a sense of self-worth (my observation is that small groups, despite often holding strong beliefs, have a low estimation of themselves).[16]

Our research builds relationships.

In our increasingly busy world, it is sometimes difficult to maintain connections to people. Research provides a reason to talk with people and naturally frames the conversation, making it easier to initiate and maintain the dialog. The result is that our work can build relationships with informants. The unique character and charm of each person emerged in the course of my interviews and drew us closer together. In Zambia, Bina Charles’ down-to-earth honesty always made me smile; Daniel Munkombwe’s tongue-in-cheek attitude amused me; and Dennis Mweetwa’s insightful observations drew me back to him repeatedly.[17] Newer connections to people like Benard Muleya provided opportunities for relationship which I expect will blossom in the future.

My renewed contact with the Old Order River Brethren re-established long-lost connections. For me, the joy of finding the tradition intact was thrilling and was a reminder of our Brethren in Christ roots.

Research also fosters new relationships resulting from new common interests. My relationship with Wendy Urban-Mead began as a simple question about her African work.[18] My connection to the archivist at Pleasant Hill, Ohio, came from an inquiry about Lila Coon. My new friendship with Webby Mwelanyika (a history researcher in Zambia) arose out his desire to find primary documents related to Brethren in Christ education. And a recent connection to a long-lost acquaintance, Peter Willms (early Brethren in Christ missionary to Japan) developed as a result of a set of color slides from 1953. I have experienced a rich and expanding network of relationships as a direct result of my research activities.

Relationships like these bind us together by deepening our understanding of common interests or common experiences. Within the context of the global Brethren in Christ Church, research helps foster a broader community of faith. Increased awareness of our common experiences encourages people to “own each other” as members of the same community of faith. This, in turn, makes it more difficult to distance ourselves from each other.

Our research sometimes helps to heal lingering hurts.

Merely saying something out loud (i.e., writing it in the case of historical research) can have a healing effect. In several interviews with David Climenhaga, he mentioned regret that he might have offended some people (e.g., Lila Coon). My sense at the time was that the act of speaking it out loud was helpful for him. Specifically acknowledging errors of the past can lead to good outcomes. Correcting or questioning errors of fact, or providing a new sense of historical balance can be a healing influence. I saw this in my relationship to the family of David Moyo. They clearly felt estranged from the Brethren in Christ, and my inquiries presented an opportunity for reconciliation. I learned later that they viewed my visit and the resulting article as a sort of restitution of their reputation.[19]

Our research gives us new insights and questions our assumptions.

Careful examinations of the facts or comparisons of different events or circumstances often open our eyes to new knowledge. The creative blending of Christian and Santali traditions in the Marandi-Hembrom wedding provides a lesson in appropriation and adaptation.[20] Although it is impossible for an outsider to know in the same way as insiders, our research can nevertheless give outsiders new understandings of unfamiliar situations. Some research raises questions about our assumptions. Oral accounts of Myron Taylor’s death from a lion attack in Zambia provide evidence to contradict assumptions about the superiority of written sources. And the example of Fred Soda offers a counter-balance to biased notions about “untrained” or “uneducated” researchers. My collaborations with Soda showed me his innate ability to tease information out of people, which led me to nurture and coach him in ethnographic research. Although not formally educated, his intuitions are extraordinary; it is merely a lack of opportunity which has limited his achievement.

Final encouragements

There is much to be done.

Completing Blest Be The Tie That Binds took longer than I had hoped. But for the most part, the work was extremely rewarding and enjoyable. However, there is a lot more work to be done. Everyone can do SOMETHING to help. Simply making audio recordings of people’s stories is important work. Even if you never transcribe the recordings or write about them, the recordings will remain. And, no person’s story is insignificant. Moreover, simply writing your own personal recollections down is important. Memories of people, places, and events will provide future researchers with the material they need to understand our time. Record your family genealogy for posterity and deposit it in the archives. If none of these activities appeal to you, assist others in their research efforts. Volunteer to scan materials for someone or help catalog or transcribe recordings. Beth Mark’s help in scanning the minutes of the Brethren in Christ Church in Africa was invaluable to me as I was writing Part 3 of “A History of Sikalongo Mission.”[21] Rachel Copenhaver Kibler and Phyllis Engle’s chronology of Sikalongo workers provided the foundation for my expanded chronology of Zambian missionary tenures. Work like theirs paves the way for other researchers. And, you can simply encourage other people to help. In 2008, Luke Keefer, Jr. wrote:

When one considers what is already in the archives, it is apparent that many more writers are needed for the journal. Historical materials are silent until someone gives them a voice. At times the journal seems like a rendition of a small musical group; what is needed is a vast chorus that could do justice to Handel’s “Messiah.” As a historical society, we must encourage new writers to contribute to the journal and other books published by the Society. [22]

Some people just need cheerleaders to keep them working. Finally, consider donating money to the society to pay for others to do research work. I have long dreamed of a fund to assist and encourage African Brethren in Christ researchers to gather and preserve historical information and materials. Ultimately, there is a lot that can be done.

There is no better time than now

Postponing research efforts “until we have the time” is a losing proposition. Waiting simply hastens the loss of data. In Zambia, an enormous amount of biographical information is already gone. As people have died, the stories of early African Brethren in Christ mission workers died with them. And every month that passes we lose more information. Hesitating also diminishes any particular individual’s potential contribution. If one delays the research effort, less time remains in one’s life to complete the work. Even if your effort seems small and insignificant, begin now.

“Ashonto ashonto” wins the day.

The magnitude of any research goal can seem overwhelming. This leads some people to despair of ever finishing and therefore they never start. The Tonga tribe in southern Zambia frequently say, “ashonto ashonto,” which means “bit by bit.” It is important to remember that an enormous amount of work can happen one small piece at a time. The collection of potential quotes can be spread over weeks, months and years. In 2009, I set up a personal database of notes related to Evangelical Visitor articles. In that year, I added several hundred entries. In the ensuing years, my database has expanded to include entries from African Minutes, the Handbook of Missions, and personal diaries; it is now several thousand entries. This database is my “go to” source for notes and documentation. Having spent the time to get started and having regularly added citations afterwards, I now have a deep reservoir of information within easy reach.

How do you start?

First, do not second guess the worth of your work; just begin with the assumption that whatever you do is worthwhile. Second, choose a task—any task—and start it. None of us is getting younger. Delaying the start simply limits your eventual productivity. Third, obligate yourself to someone, even if you ultimately fail to meet the deadline. I, for example, had hoped to finish Part 4 of the Sikalongo history for this edition of the journal. Unfortunately, some unexpected research findings made it clear that the result would be incomplete if I rushed the finished product. Our editor, Harriet Bicksler, graciously forgave my failure to deliver on my promise to have it ready. However, the deadline kept pushing me to keep working. Fourth, ask for suggestions; someone will give you direction. Some people are really good at brainstorming possibilities. Take advantage of other peoples’ suggestions. You might be surprised at the available options and one or two of them might inspire you to act. Fifth, do not keep your work to yourself. Share it with others, either through writing or in some other way. Lastly, start SOMETHING. Even if you do not have an ultimate goal in mind, start something. Any activity usually leads somewhere.

In the Bible, the word “knowledge” typically means “understanding.” This, after all, is the ultimate goal of research; we seek to understand. Our research helps us understand ourselves, the world we live in, and those who inhabit our present world and those who lived in the past. I trust I have made the point that the quest for knowledge through intentional research is not merely an end in itself (though it is that), but that the process of researching reaps secondary benefits that reflect the love of God. Through research we gain knowledge, but we also sustain our values, build relationships with others, and communicate our love for people and our concern for their lives. The combination of all these ends makes our efforts worthwhile.

Endnotes

[1] Clifford Geertz, Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (New York: Basic Books, 1973); Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1983); “‘Local Knowledge’ and Its Limits: Some ‘Obiter Dicta,'” The Yale Journal of Criticism 5, no. 2 (1992): 129-135.

[2] Dwight W. Thomas, “A Study of Meaning in Three White Gospel Music Traditions of Central Pennsylvania” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1995).

[3] Edward Muir and Guido Ruggiero, Microhistory and the Lost Peoples of Europe: Selections from Quaderni Storici (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991); Carlo Ginzberg, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know About It,” Critical Inquiry, 20, no. 1 (Autumn 1993): 10-35.

[4] Sigurdur Gylfi Magnusson, “What Is Microhistory?,” History of News Network, May 7, 2006, http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/23720#_edn2.

[5] E. Morris Sider, “Historical Writing in the Small Denomination: Problems and Challenges in Microhistory,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 20, no. 1 (April 1997): 115.

[6] Donald F Durnbaugh, “On Writing Denominational History: The Mennonites in Canada Series,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 22, no. 2 (August 1999): 291-304.

[7] Luke Keefer Jr., “Celebrating Thirty Years of Brethren in Christ History and Life,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 31, no. 3 (December 2008): 507-526.

[8] Franz Boas, The Mind of Primitive Man, a Course of Lectures Delivered before the Lowell Institute, Boston, Mass., and the National University of Mexico, 1910-1911 (New York: Macmillan, 1911); Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, a Study in Religious Sociology (London: G. Allen & Unwin, 1915); Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Scribner, 1930); Ruth Benedict, Patterns of Culture (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1934); Gregory Bateson, Naven: a Survey of the Problems Suggested by a Composite Picture of the Culture of a New Guinea Tribe Drawn from Three Points of View (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1936); Bronislaw Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion: And Other Essays, (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1948); Raymond William Firth, Elements of Social Organization, Josiah Mason Lectures, (New York: Philosophical Library, 1951); A. R. Radcliffe-Brown, Structure and Function in Primitive Societ: Essays and Addresses (Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1952); Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked (New York: Harper & Row, 1969).

[9] Edwin William Smith and Andrew Murray Dale, The Ila-Speaking Peoples of Northern Rhodesia, 2 vols. (London: Macmillan, 1920). Frances Densmore, The American Indians and Their Music (New York,: The Woman’s Press, 1926).

[10] Dwight W. Thomas, Blest Be The Tie That Binds: Studies in Global Brethren in Christ Faith and Culture (Mechanicsburg, PA: Brethren in Christ Historical Society, 2017), chapters 1-3.

[11] Dwight W. Thomas, “Tracking the Hunter: Oral Accounts of Myron Taylor’s Death,” in Blest Be The Tie That Binds: Studies in Global Brethren in Christ Faith and Culture (Mechanicsburg, PA: Brethren in Christ Historical Society, 2017), 127-160. Hereafter, the abbreviated title, Blest Be the Tie That Binds, will be used.

[12] Thomas, “Ndhlalambi (David) Moyo: Early Africa Mission Worker in the Zambian Brethren in Christ Church,” in Blest Be the Tie That Binds, 85-126.

[13] Thomas, “Inyimbo Zyabakristo: Chitonga Hymnal of the Zambian Brethren in Christ Church,” in Blest Be the Tie That Binds, 187-228.

[14] Thomas, “Isai Santal Bapla: A Santal Brethren in Christ Wedding in Bihar, India,” in Blest Be the Tie That Binds, 231-270.

[15] Thomas, “Inyimbo Zyabakristo: Chitonga Hymnal of the Zambian Brethren in Christ Church,” in Blest Be the Tie That Binds, 187-228.

[16] Sider, “Historical Writing in the Small Denomination: Problems and Challenges in Microhistory,” 114.

[17] Sara Muleya, Daniel Munkombwe, and Dennis Mweetwa. Interviews with the author.

[18] Wendy Urban-Mead, a professor at Bard College, has done major research among the Brethren in Christ in Zimbabwe; for example, see Wendy Urban-Mead, The Gender of Piety: Family, Faith, and Colonial Rule in Matabeleland, Zimbabwe (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2015).

[19] Thomas, “Ndhlalambi (David) Moyo: Early African Mission Worker in the Zambian Brethren in Christ Church,” in Blest Be the Tie That Binds, 85-126.

[20] Thomas, “Isai Santal Bapla: A Santal Brethren in Christ Wedding in Bihar, India,” in Blest Be the Tie That Binds, 231-270.

[21] See Dwight W. Thomas, “A History of Sikalongo Mission, Part 3: Indigenization and Independence at Sikalongo, 1947-1978,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 40, no. 2 (August 2017): 201-270. Parts 1 and 2 appear in the December 2016 and April 2017 issues of Brethren in Christ History and Life.

[22] Keefer, Jr., “Celebrating Thirty Years of Brethren in Christ History and Life,” 516.

I enjoyed reading your blog about historical research of the Brethren in Christ Church at Sikalongo Mission. As a former pupil at Sikalongo I remember a few interesting characters like Miss Kettering (sic) who taught me English with an American accent. I was a pupil from August 1956 until May 1960 when I left to continue my education at Kafue Secondary School from 1960 to 1962. I have always wondered what happened to Miss Kettering after left Sikalongo. I also wondered where she hailed from in the US. My guess was that she came from the state of Pennysylvania. I was born on 28 April 1944. I happen to know my exact date because I was fortunate to have for a father who went to school at Sikalongo and wrote down the birth dates of his seven children in his Bible. Otherwise I would never have known my date of birth.