On May 3, 1903 from her post at Matopo Mission in Southern Rhodesia in southern Africa, H. Frances Davidson ((For biographical information see Morris Sider, “Frances Davidson,” in Nine Portraits: Brethren in Christ Biographical Sketches (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978), 159-214.)) penned a letter to three of her sisters, Ida Davidson Hoffman,1 Lydia Davidson Brewer,2 and Carrie Davidson Landis.3 The post carrying the sad news of their father Henry B. Davidson’s death on March 17, nearly two months earlier, had finally reached her, having made its way by ship across the Atlantic Ocean and inland by rail to Bulawayo. The act of writing a letter provided a way for Frances to feel connected with her family despite the great geographic distance that separated them.4 It evokes the grief that Frances experienced, as she absorbed the news of their father’s death:

Again the Lord has seen fit to visit our family and to take a dear one to Himself. It is difficult to realize that it is actually true that dear father has left us but two letters last week sent the same sad tidings, sad to us who shall so greatly miss him. . . he is gone, we shall never more see his dear face or receive his loving counsel and we shall miss him so much. . . .5

From the middle of the nineteenth century, postal services had provided a means whereby family members, many of whom were far flung in an age of great mobility, could find solace and support one another. They could participate in family life, retaining a sense of intimacy even from great distances.6 Well over a century later, readers still experience something of Frances’s heaviness of heart as she mourned from afar:

I think it is very fitting that he should be buried at Wooster as so many years of his life were spent there, and I suppose it was his wish to be buried there…. How does Mother’s grave and lot look? Has anything been done to it or has it been neglected? If so won’t some of you please have it fixed up and plant something on it. . . . I’ll enclose a few white cosmos. . .flower seeds which I wish you would plant on it and sometime I’ll send some for Father’s grave.

Six and half years earlier in October 1894, Frances had expressed her deep sense of loss at her mother Fannie Rice Davidson’s death.7 By the time the news of her father’s passing reached Frances, he had been buried in Wooster, Ohio, far from Fannie’s last resting place in Abilene, Kansas. He would lie next to his first wife Hannah Craft Davidson, and alongside the husband and son of their eldest daughter Mary Davidson Yoder.8 It must have provided comfort for Mary, who had buried her husband Christian and son Isaiah close to her mother, and for Mary and her siblings—Sarah Davidson Coup, Carrie Davidson Landis, William Davidson and Isaiah Davidson—who had been left motherless as small children nearly 50 years earlier. Henry’s burial next to their mother completed a circle long broken.9

For Henry Davidson’s second family, Frances and her seven siblings—Lydia Davidson Brewer, Rebecca (Becky) Davidson Dohner, Emma Davidson Diehl, Henry Davidson Jr., Henrietta Davidson Brechbill, Albert Davidson, and Ida Davidson Hoffman, dispersed as they were from Kansas to Colorado to Indiana and across the sea to South Africa—it symbolized the family’s fragmentation to have their mother lying alone in Abilene.10 Frances’s letter written from southern Africa to her sisters in Kansas suggests that even from the distance brought by mobility and death, there was a force that maintained the family unit. Thoughts of white cosmos growing from seeds shipped from her home on the dark continent perhaps alleviated something of the deep loss that Frances felt both in the geographic dispersal of the family and in the ultimate separation of death.

This letter, written by a daughter who had been greatly influenced by her mother, and who had worked closely with her father helping to embody his vision for mission, opens the way for exploration into the life of Henry B. Davidson and his second wife Fannie Rice Davidson, during the 40 years of their shared ministry, and the strong family bond that supported it. Fortunately, Frances Davidson’s diaries, letters, and frequent submissions to the Evangelical Visitor provide glimpses into the Davidson vision and family life, for few of Henry’s writings have survived; nor have letters or other materials penned by Fannie been discovered. Indeed, far more is known about Frances than her father, who was instrumental in launching what quickly became a bi-weekly transnational periodical that would survive for just over 125 years and, to cite Micah Brickner, has “inspired the church for decades” [and] will continue leading us in the twenty-first century.”11 Frances’s writings, issues of The Evangelical Visitor published between 1887 and 1896 under Henry’s editorship, genealogical materials,12 denominational histories, local accounts, along with secondary literature provide fragments from which we can piece together Henry B. and Fannie Rice Davidson’s story. Long hidden in the fog of the past, their significance in bringing the Brethren in Christ into the transnational history of evangelical Christianity in the United States, Canada, and Africa, is well worth exploring.13

With his vision and clear-headed leadership, Henry Davidson was the driving force in converting a separate people to the use of contemporary tools of communication that would keep a community together during years of expansion. Indeed, one could argue that the Evangelical Visitorwas foundational in creating a denomination, as Americans continued the pioneer trek west and north during the late nineteenth-century; it even created the potential for a global vision.14 Fannie Rice Davidson’s role is not to be overlooked, for it was key to her husband’s ministry. As cultural historian S. J. Kleinberg has emphasized, gender is “one of the dominant influences in American life and culture.”We can be sure that Fannie shared Henry’s legacy, and even shaped it, if “from a perspective infused with cultural beliefs about appropriate female roles.”15

Scotch-Irish and German heritage

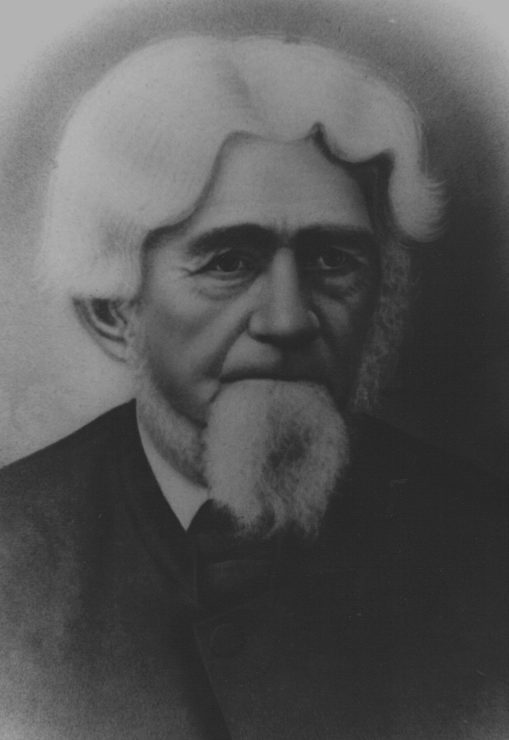

Henry B. Davidson was born in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania on April 15,1823, the seventh of Jacob and Mary Magdalena Young Davidson’s eight children. Just over 40 years of age when Henry was born, Jacob was well established. By this point he had become a wealthy farmer who, through his mill wright operation, supplied millstones to farmers west of the Alleghenies. A lay minister for the United Brethren in Christ, he downsized his farm operation by divesting a substantial piece of land to the new municipality of Madison, at the same time accepting the appointment of postmaster.16

Henry’s grandfather Robert Davidson had been a Presbyterian minister, who was among the tens of thousand of Scotch-Irish that immigrated from Ulster before the American Revolution.17 To cite historian William Sweet, “the most energetic, the most active-minded of those of Presbyterian faith,” the Ulster immigrants sought “a new place of refuge with economic stability and a more egalitarian ecclesiastical status” than was available for them as Scots in Ireland.18

Jacob had been orphaned at an early age, and apprenticed as a mill wright with the Niesley family, Pennsylvania-Dutch folk from Hummelstown, Dauphin County who raised him.19 The massive burr millstones that he learned to craft may have been as much as six to seven feet in diameter, weighing up to two tons; essential to producing the quality flour which was the mainstay of the colonies in those years, they provided a lucrative living alongside farming.20 The 20-year-old Jacob’s marriage to Mary Magdelena Young, just 16, whose parents had emigrated to Lancaster from Baden, Germany, meant that Henry and his siblings would grow up in a home with a mixed heritage.21

On January 11,1831 when Henry was nearly eight years old, Fannie Rice was born just south of Westmoreland in Fayette County. The fifth child in Samuel and Frances Strickler Rice’s family of 11, Fannie was the daughter selected to carry her mother’s and grandmother’s name.22 Seven of the younger children are listed in the 1850 census by the surname of Aleberger, suggesting that they may have been a family of orphans raised by the Rices; whatever the case, they were recorded in the family Bible.Like Jacob Davidson, Fannie’s father Samuel had been orphaned at an early age and adopted into a Pennsylvania Dutch family; we know little more than that he was influenced by the Church of the Brethren.With the Strickler heritage of a substantial inheritance for all their children, both boys and girls, Samuel and Frances Rice appear to have been well positioned farmers on Fayette County’s Youghiogheny River in Fannie’s growing up years.23

Henry’s Scotch-Irish and German parentage and Fannie’s Anabaptist background rooted in Alsace-Lorraine place them in the two ethnic groups that dominated colonial Pennsylvania. Although the Scotch-Irish were the most widely scattered, no one group held a majority, and they were integrated along with the variety of German immigrants including “Mennonites, Dunkers, Moravians, Schwenkfelders, Lutherans, German and Dutch Reformed” that had responded to William Penn’s invitation to religious groups to settle in Pennsylvania.24

Both the Davidson and the Rice families had been influenced by the evangelistic preaching, spontaneous interpretation of Scripture, and understandings of conversion inspired by the first Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s. The spiritual awakening that occurred during the revivals of this period continued to have an impact until the end of the eighteenth century and inspired members of Pennsylvania’s German immigrant communities who formed new denominations like the United Brethren in Christ, River Brethren (Brethren in Christ), and Dunkers (Church of the Brethren). All of these denominations played a significant part in Henry’s and Fannie’s story. These denominations moved in close circles, for instance at times sharing meeting house space; with Presbyterian and Church of the Brethren influence, both the Davidson and Rice families appear to have associated in the United Brethren in Christ community in Henry and Fannie’s growing up years.25

Emerging in 1767, in historian Carlton Wittlinger’s words, “[t]he central theme”of the United Brethren in Christ“was a personal, heartfelt experience of the new birth,” withpublic testimony expressed by both men and women.26 In its early days, under the leadership of Mennonite leader Martin Boehm and German Reformed minister William Otterbein, this ecumenical movement encouraged converts to stay within their own denominations. Known for its relationships with both German and English-speaking groups, and with no preferred age or mode of baptism—infant or adult—sprinkling, pouring, or immersion were equally acceptable. With its wide swath, the United Brethren in Christ expanded rapidly from eastern Pennsylvania south to Virginia, east to Maryland and as far west as Pennsylvania’s Westmoreland County. In 1815,leaders met in Mount Pleasant to present a formulated “discipline and confession of faith” that would make the United Brethren in Christ the first denomination founded in the United States.With the gathering’s close proximity to the respective Rice and Davidson home sin northern Fayette and southern Westmoreland Counties, as ministers Jacob and Samuel may well have been present.27

A description of a minister’s preparation and qualification for ministry, published in the United Brethren in Christ Religious Telescope four decades later in 1853, gives a glimpse o fthe high standards placed on the preachers who served the denomination. Henry and Fannie had both reached early adulthood by this point; nonetheless Isaiah Potter’s ideal view gives a glimpse of the standard to which their fathers were held as ministers:

[A minister] should be thoroughly furnished with information relative to the salvation of man. . . . Education is important to a minister’s success, but not more so than deep humility, fervent zeal, a feeling sense of his responsibility, the value of souls, and a call to the ministry. I am decidedly opposed to licensing an ignorant man to preach the gospel; but not more so, than to license a literary cox comb, or a phlegmatic drone. . . . We want men. . . who are intelligent, and who have at least a good common English education, and a pretty thorough knowledge of Bible doctrine; but they [United Brethren] require this no more than they do men of deep-tonal piety, humble men, and men who souls blaze with zeal like torches.28

There was little by way of salary, and if a minister were to fulfill his obligations to itinerate, he needed the full support of his wife and children. His wife, with the help of the children, would run the family farm while he travelled from preaching point to preaching point. During Henry’s and Fannie’s growing up years, these trips—as much as 150 miles—were made on horseback, through all kinds of weather.29 To make it possible for their minister husbands to serve the church, we can imagine Frances Rice and Mary Magdalena Davidson taking on farm management, in addition to their household work, to sustain the family enterprise.

The willingness of a minister’s wife to submit in obedience to husband and church, as she took on enormous responsibilities while her husband was away, was essential to effective itinerant ministry. As a boy, Henry would have been answerable to his mother as she directed Davidson farm operations; Fannie would have been called on to help run the Rice household. Days could lead to weeks and even months before a husband and father’s return.30 Along with the physical duties, Fannie and Henry would have learned the basic three ‘r’s’from their mothers. Much of what they learned of the rituals that passed on the faith including Bible reading and prayer would have been at their mothers’ knees.31 Women also provided hospitality for visiting preachers.In Henry Davidson’s and Fannie Rice’s growing up years, their mothers Mary Magdalena Young Davidson and Frances Strickler Rice were among the models of industry and strong women of faith who made it possible for their fathers, in Funk’s words, to “make extreme sacrifices in order to preach the Gospel” in service as lay preachers in the United Brethren in Christ community.32

From Westmoreland to Fayette County

The Davidson and Rice homes would have held much in common with other United Brethren in Christ ministers, but there also must have been differences. In contrast to Fannie’s upbringing, which was similar to the majority of Pennsylvania German farmers “who, once they found a home, tended to remain fixed,” Henry grew up in a Scotch-Irish community. His youth was coloured by the Scotch-Irish “impetuosity” and “mobility” that had caused Jacob, in his youth, to migrate from Lancaster County to west of the Allegheny mountains where other Ulster immigrants had settled.33

The Scotch-Irish restless and enterprising spirit saw the Davidsons uprooting in mid-life, to resettle in Fayette County, just south of Westmoreland. Leaving farm property in the hands of Henry’s eldest brother Samuel, Jacob and Mary re-established themselves and their younger children among the Scotch-Irish and German communities along the Monongahela where it flowed into the Ohio River. Although the record is silent regarding their motive for the move, the town of Brownsville where they situated themselves was an important centre on the National Road that provided “a route through the mountains for settlers heading west.”34 The family’s re-location to this thriving industrial community with its shipyards and strong economy would shape 14-year-old Henry’s destiny.

Jacob purchased the large tavern on the Basil Brown tract two miles east of Brownsville that he and Mary Magdalena would convert into a large home. Built as a hotel in 1812, for 25 years it had been frequented by wagoneers and drovers. Now in their 50s, the senior Davidsons shared the home with their son Jacob Junior and his wife Hannah Kelly Davidson and their growing family, along with their own children still at home. What was the push for this move? It may have been to leave their mill wright enterprise behind, and to give the younger children a new start in a thriving industrial centre. Indeed, Jacob Jr. must have been showing signs of silicosis, the disease caused by “breathing of rock dust,” with its symptoms of coughing, loss of appetite, and strength that took its toll after only a few years of working in the millstone industry, and would cause his early demise.35 Perhaps Jacob himself also suffered from the disease.

With his financial success gained by decades of industry as farmer and in the millwright trade, Jacob was able to buy substantial property, and immediately became a prominent town figure with his appointment as a director at the local Monongahela Bank, established some 20 years earlier.36 Public education had only been launched in Pennsylvania in 1834, so Henry’s education was informal.37 Yet, while Fannie was still a child growing up on the Rice family farm, the thriving “mercantile sector,”. . . consisting “of some fifty stores, several of which were wholesale and forwarding houses, dealing in a full range of supplies—dry goods, clothing, boots and shoes, hats, grocers, produce, hardware, iron, drugs, books . . .” and hotels and taverns for travellers, provided Henry with an education that would serve him well. As he matured into adulthood, he would take full advantage of the unique employment opportunity that gave him a view of the industrial world, including seeing the potential for migrating westward.38

Fannie was only 13 years old in 1844 when Henry married Hannah, the daughter of United Brethren in Christ minister George B. and his wife Sarah Radcliff Craft. Henry was 21. Even as he was establishing a family with marriage into this prominent Brownsville family, the local economy dramatically dropped. Henry’s and Hannah’s future, and ultimately Fannie’s, would be influenced by the economic downturn in what had been until then a thriving community. The extension of the railroad, making it possible to bypass the water traffic on which the Brownsville economy depended, would, in effect, eliminate the centre as a major connecting place in the immigration west. With his proximity to the hub, and his father’s place at the bank, Henry must have seen the decline coming; the town’s prominence dramatically ended with “travel by stage, wagon and steamboat” giving way to the railroad.39

Meanwhile two years into his life with Hannah, Henry was ordained. Settling into the tiny Fayette County River Brethren community is puzzling; his father and his father-in-law served as ministers in the much larger United Brethren in Christ denomination; his grandfather had been ordained in the Presbyterian church.40 Perhaps Henry’s mother’s Lancaster County connections brought him into contact with the River Brethren; they did hold similar values and practices as the United Brethren in Christ, including the Anabaptist influence manifested in their common pacifism and strong communities. As the United Brethren in Christ had become preoccupied with institutions and structures, he may well have been drawn to the less formal and more enthusiastic worship and warm spiritual expression of the River Brethren. Whatever the reason, in this time of “extraordinary mobility in the United States,” as Henkin has named it, the push of a declining economy in Brownsville, and the pull of a call by the small group of River Brethren in Ohio, found Henry and Hannah immigrating west.41 In that environment Henry would develop as a leader, holding significant influence in his chosen denomination, and when Hannah died an untimely death, Fannie’s and Henry’s lives would come together.

Westward to Summit County, Ohio

W. O. Baker’s reflections on his conversion into the River Brethren community at Paradise, at the time of the Davidsons’ immigration to Ohio, give a glimpse into Henry’s early ministry. Baker recalled how after completing his teacher training in nearby Wooster, he went out to Paradise, Ohio to teach and heard several Brethren preach in the Benner home:

In the winter of 1851 to 1852 in a series of meetings held at the Paradise church I was convicted of sin and made a public start in the service of God. I did not surrender myself fully to Christ, hence I was not saved then. In the latter part of the year 1853 I was again convicted, more powerfully, by God’s Spirit, at the same place, and making the entire sacrifice, God exercised his great mercy toward me in the pardon of my sins. Praises unto his holy name!42

Having settled his family in Bath among folks he described as Yankees, Henry would travel monthly with other preachers from Stark and Summit Counties to serve the tiny Wayne County group; he would take his turn preaching at their services in the solid brick union meetinghouse built in 1841 by the Paradise Church of the Brethren on a corner of Cyrus Hoover’s farm.43 Baker’s description of his conversion illustrates the piety that the River Brethren shared with their sister community: “[I] was again convicted, more powerfully, by God’s Spirit, at the same place, and making the entire sacrifice, God exercised his great mercy toward me in the pardon of my sins.” Reflecting further, Baker described the perceptions of the River Brethren by the local community where he lived and taught: “[I]t was said that these brethren claimed to be possessed of the Holy Ghost. This seemed to me a high attainment. But from what I know of the word of God I believe that it ought to be so. I learned that they were generally accounted as Christians in the neighbourhood.” Henry Davidson witnessed Baker’s joy in his baptism in late February 1855, when Jacob Hoffman baptized him in the cold waters of Sugar Creek into the tiny fellowship of River Brethren. As Baker expressed it, “[t]hat evening I almost felt as if I had entered the Land of Beulah. From this time I was numbered with the little flock.”44

Although Baker would move on to Ashland to take up a career in medicine, Davidson would re-locate to Wayne County, where he established his growing family on the highly arable land once farmed by an indigenous population. For the next 25 years, he made his life among the Pennsylvania German immigrants with such names as Zimmerman, Harzler, Amstutz, Conrad, Martin, Yoder, Myers and Stuckey who were establishing communities of Amish, Church of the Brethren, and Henry’s denomination of origin, United Brethren in Christ.45 From Ashland County where William Baker would make his life as a family doctor, he and Henry Davidson would become fast friends and colleagues, working together amidst the difficulties that life brought them, to help build the community of River Brethren that was emerging in Ohio.

Three years after settling in Ohio, tragedy struck the Davidson household. As it did in so many homes of the era, the spectre of death came in the form of typhoid fever. On May 31, 1855, 31-year-old Hannah succumbed to the disease, leaving five children motherless. Bereft as a young father, farmer and preacher, Henry needed a wife. It would be no easy task to find someone to fill in for a beloved companion, a woman who could capably mother five small children, all the while managing a farm household, and fulfilling the demanding expectations of a minister’s wife. And yet there was little option, for in that era marriage was key to a man’s success.46

As Kleinberg has explained, it was common for widowers to advertise for people to provide household help who had “an ‘unsullied reputation’ who would manage the ‘female concerns of country business.’” In her words, “[t]he list of jobs included ‘[raising] small stock, dairying, marketing, combing, carding, spinning, knitting, sewing, pickling, preserving, etc.’ and occasionally instructing the daughters of the household in the domestic economy.”47 But for a young man, love was also important. As Errington has put it, in the nineteenth century “[a] woman and man, it was believed, should marry for love and their subsequent relationship should be based on mutual trust and affection. . . . [A] family was . . . expected to be a haven and a place of solace and strength for all its members.”48 In Henry’s case there was even more at stake. As father to five small children, and a minister, he sought more than conjugal love; his wife would need to embody love for his family, and equally important, for his calling. His next wife would need to be someone who would be willing to commit in obedience and submission to the church he served.49

With these considerations, and newly settled among Ohio Yankees with only a tiny River Brethren community, it comes as no surprise that Henry returned to Pennsylvania to the United Brethren in Christ community in which he and Hannah had been married to search for a wife. By spring, just 10 months after Hannah’s demise, a letter to her parents indicated that he had met with success. On March 1, 1856, Henry gently informed the Crafts that during a visit with friends near Mount Pleasant, he had “formed an attachment for a young lady of about twenty-five years of age, of respectable parents, and I suppose I may say, wealthy parents, and which from every appearance now will likely result in a marriage before long.” The Davidson and Rice connection was a long one, Henry assured his former parents-in-law;50 and it was strong, as the recent marriage of Henry’s niece Mary to Fannie’s elder brother John implies.51

With this close relationship, it is safe to assume that Hannah’s parents also would have known the Rices as part of the United Brethren in Christ ministry circle. Emphasizing Fannie’s suitability as a mother for their grandchildren, Henry stressed that she also had been a close friend of Hannah’s. As was typical for young women of the era, she had travelled out to Ohio and stayed with the family several times. In his words,

I have, I may say, been intimately acquainted with her since I have lived out here. She has been in our family often and lived with us a week or two at a time during Hannah’s lifetime and has been here once or twice since Hannah’s death.52

According to family lore, Fannie was less enthusiastic than Henry about the arrangement. As historians of women have noted, “marriage was a defining event in a woman’s life,” determining “where she lived,” and “her social and economic status.”53 Young men had more control over their destiny, even after marriage. A woman’s life was lived out in the home, with “a future shaped by marriage, child-bearing and family responsibilities.”54 Henry’s optimistic “from every appearance” overlooked one thing: Fannie’s uncertainty about taking on responsibility for five young children.55

At the same time, by age 25, Fannie had reached what was considered spinsterhood in the mid-nineteenth century.56 It was a difficult decision for a young woman to take on the rigorous duties of a domestic situation that included raising five youngsters, including an infant. She would be living far from home, without assistance from her family, or the possibility of caring for her parents in their old age. For Fannie, as for most women of her era, in Errington’s words, “[t]he question was not whether to marry, but when to marry.” Mutual affection, companionship, and the independence and autonomy of running a home were important for a young woman as she came into adulthood.57

Whatever her motivation, Henry successfully wooed Fannie. As most women of the era, she had certainly been apprenticed by her mother in what it meant to be a woman, with its central role of motherhood. She also would have learned the variety of skills necessary to run a farm home including “dairying, how to plant, weed, and harvest vegetables, care for chickens, spin, weave, and sew,” with plenty of opportunity to practice as older sister to six younger siblings. Thus it was that on April 10, 1856, Fannie Rice committed to a new life that would take her to Ohio with the benefits and challenges that it implied. She and Henry Davidson would begin a life together in Summit County.58

From Summit to Wayne County

Two years after their marriage, Henry moved his growing family that now, along with Hannah’s five—Mary, Sarah, William, Carrie and Isaiah—included Fannie’s new baby Lydia, to Wayne County. Having purchased a farm near Smithville, they would be closer to the little River Brethren community where W. O. Baker had been baptized two years earlier. With the growing presence of the Church of the Brethren, and a United Brethren in Christ church in the area dividing the German population, the Davidsons must have been a welcome asset to the tiny River Brethren community. According to Baker’s “Recollections,” when the family “moved into the church” it was still “composed of the four old members.”59 What with Henry’s vision and calm leadership style, Fannie’s capability and commitment as a minister’s wife, and the rapidly expanding Davidson family, the church would grow to become a significant presence in Wayne County.

Within two years of the Davidsons’ 1855 move, the Paradise church found itself in the midst of the Civil War, which Ray Heisey has called “the most horrendous war in the history of the nation.” The River Brethren, like other German sectarians including the United Brethren in Christ, had always eschewed slavery; living as they were in the hotbed of abolitionist and anti-slavery rhetoric that came to a head in Ohio and neighbouring Indiana, some signed up. The United Brethren in Christ long had been vocal in its stance against slavery, and recorded a large number who enlisted, including ministers. Stories tell of River Brethren also volunteering in a variety of ways. Some hired substitutes or paid the $300 commutation fee based on the annual salary of a worker; others enrolled as non-combatants. With the 30,000 volunteers that responded to “Lincoln’s first call in 1861,” it is unlikely that any Ohio River Brethren were drafted, but the varied responses among the pacifist sects prompted leaders to officially communicate their nonresistant stand to Washington.60

Wittlinger has noted that “[t]he sources are silent about the reasons why the they chose to substitute” Brethren in Christ “for the familiar ‘River Brethren’,” in this official communication with government.61 Whatever the motivation, the decision must have felt familiar to Henry Davidson with his background in the United Brethren in Christ. Indeed, under Davidson’s leadership, the fledgling Brethren in Christ would be ushered into the nineteenth century evangelical movement, slowly embracing print communication, mission, and education.62

Having grown up in a Scotch-Irish home, Davidson was a product of the long history of literacy that Arthur Herman has emphasized had become, already by the late eighteenth century, “a way of life” in Scotland.63 The United Brethren in Christ had long embraced the possibilities of the postal age, having established a denominational printing press in Ohio in 1833 when Henry was a 10-year- old boy. An avid reader, he must have seen the vocal promotion of abolition and temperance in the denominational Religious Telescope. He would have been fully apprised also of the denomination’s steps towards mission; he may have followed developments that led to the founding of a Missionary Society 20y ears earlier, and observed how it embodied abolitionist sentiments by sending the denomination’s first missionaries to Sierra Leone in 1855. If Davidson’s close association with W. O. Baker, who is thought to be the most educated person of the time among the Brethren in Christ, is any indication, he would have also followed the developments in higher education that led to the 1847 opening of a United Brethren in Christ University in Westerville, Ohio. Similar to Otterbein University, as it was called, both men held a high view of education for women. Henry Davidson’s life experience and vision would greatly influence the denomination as it differentiated itself from what became the Old Order River Brethren.64

History makes much of such conflicts as the Civil War and the institution building so important in times of social change, but as Quaker sociologist Elise Boulding has suggested, “the missing element in social awareness of the nature of human experience through history . . . is an image of the dailiness of life—of the common round from dawn to dawn that sustains human existence.”65 For farming communities like the one that shaped the Brethren in Christ in Smithville, Ohio, their faith was sustained by the continuity of life, season after season, living out each day as it came. For women, the self-sacrifice required in bearing, nursing,and raising children was their major pre-occupation; with its dangers both for mothers and small children, the suffering implicit in the centrality of motherhood provided a glue for kinship networks of women, and gave focus to all of the other duties of running a farm and maintaining family, including the most important task of preparing each child for eternity. It was the steady attention to the details of daily and seasonal life on the farm, and the mother’s role in creating the sacred and safe space called home, that provided the foundation for faith, and for a man’s public roles.66

The quickly multiplying Davidson family, soon to become the largest in the area, bolstered Henry’s leadership, helping to make the Brethren in Christ community a visible presence. Not only did Rebecca, Frances, Emma, and twins Henry and Henrietta come in close succession, by 1866 Fannie’s parents had immigrated from Pennsylvania, adding another preacher and wife with their younger children to the community. It is hardly surprising, with Fannie’s heavy load, that her parents, as they approached old age, sold their property in Fayette County, and brought their family to Ohio. Women of the era and their aging parents typically counted on relatives to help them.67

Samuel purchased the Davidson Georgetown farm, while Henry and Fannie and the nine younger children made a new home in a large frame house on the western edge of Smithville. Despite having been “afflicted with that terrible disease, cancer” already during that time as her obituary would declare 30 years later, Fannie survived two more pregnancies, bringing her last child into a wintry Ohio world at 39years of age. Ten days after Fannie’s mother Frances drew her final breath on December 10, 1870, Ida Alice completed the family, bringing it to its final count of 13 children.68 While Samuel would move further west, taking Cyrus and Samuel Jr. to join sons Henry and John who farmed in Illinois, the Davidsons made what would be their final Ohio move to Rich Valley farm just north of the town of Easton.69

Fannie Davidson’s devotion and deference to her husband’s well-being, through ill health, pregnancies, and constant attention to children ranging from infancy to young adult, gave balance to Henry’s leadership in the church, and the risks that his Scotch-Irish initiative imposed on their family life. Records are scant, but the memory remains of Sarah Davidson Coup coming home during Fannie’s child-bearing years to give birth to a daughter. The household would have been full and must have taken strong managerial skills to keep it running smoothly.The buying and selling of farm properties, that gave Henry the reputation of being, in a great granddaughter’s words, “the buyingest man of his time in Wayne County” was sustained by Fannie’s management of the family’s moves from house to house.70 As historians of women have disclosed, a man’s success depended on his wife’s management abilities. Fannie’s long-suffering presence nourished their home, especially during the frequent absences that his ministry demanded. Indeed, Fannie was the centre; she held the power required to create a home in the best of times, and demonstrated a formidable strength that sustained family life amidst upheaval practically unheard of among the quiet farmers in the largely German community where they lived.71

The last farm Henry Davidson purchased during their time in Ohio would be among those lauded in a spring 1872 edition of the Wayne County Democrat, in “a county noted for its pleasant places, and in which the many beautiful and well cultivated farms and fine residences give ample evidence of the industry, thrift and consequent wealth of its farming communities.”72 History is silent regarding Henry’s financial resources, but he may have received an inheritance from his father; records do show that like Jacob, who had passed away within days of his Henry’s to Fannie, Henry was wealthy in property and held prominence in his community.73

An 1873 map of Wayne County delineating farm properties confirms that the Davidsons were counted among these wealthy citizens. With the purchase of additional land, the Davidson property was 50 percent larger than any other in the neighbourhood, and triple the size of many. With the brick house built on the property, the Federal Census of 1870 gave Henry a real estate value of $23,500 with a personal estate of $2500, well above what neighbouring farmers were worth; for instance, the farm of his closest neighbour, Jacob Doner, was evaluated by the assessor at $12,800 with a personal estate of $1800. Similar to other farmers who supplemented their family living by working as butchers, blacksmiths, ditch diggers, tanners, carpenters, stone workers and threshers, further remuneration from the cheese factory Henry ran in Easton for a time would have also helped feed the many mouths in the household and provide them with an education.

If the Davidsons are any indication, the Brethren in Christ community must have been viewed by the surrounding community in as positive a light as their sister denomination immortalized by a glowing report on the Church of the Brethren (German Baptist) council published on May 22, 1872 in the Wayne County Democrat: “Despite their peculiarities of Faith, which they consider nothing without Works, the reporter described them as thrifty, economical, industrious and the best, wealthiest and mildest of citizens.” Railroads crisscrossing the country brought no less than 5,000 German Baptists to the Hoover farm in Paradise where Henry’s friend and colleague W. O. Baker had been baptized into the River Brethren community some 15 years earlier. Delegates to this Church of the Brethren council included six hundred preachers, arriving from Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Missouri, Kansas, New Jersey, Minnesota, and Michigan, along with the editor of the denomination’s Gospel Visitor. ((“German Baptist Church,” 18-19; see also Durnbaugh, Fruit of the Vine, 320; Martin Marty, Pilgrims in their own Land: 500 Years of Religion in America (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), 310.)) Although history is silent on Brethren in Christ involvement with this particular council, according to Wittlinger, with the closeness in their belief and practice, the two denominations had considered merging.74 Indeed, 15 years later, the Brethren in Christ were ready to launch their own publication with a strikingly similar name.

From Wayne County to White Pigeon Michigan

From an office in his home on the Michigan frontier, Henry led the Brethren in Christ into the world of communication so important to the shaping of nineteenth-century institutions and movements.75 In the summer of 1887, 15 years after the large Church of the Brethren gathering had left its mark on Smithville, Ohio, Henry Davidson sat in his office in the family’s large frame home in White Pigeon, Michigan, and carefully penned his first editorial for the Brethren in Christ Evangelical Visitor:

We have long since felt the necessity of just such a church paper, and now, since it has been established through the action of our last General Conference, we will state here that we desire and by the help of the Board of Publication and the cooperation of the church in general expect to give all our energies to the work. . . .76

In 1874, two years after the noteworthy Church of the Brethren presence in Smithville, certain Michigan members had petitioned the Brethren in Christ General Conference for their own church paper. Had the prominent presence of the former’s Gospel Visitoreditor James Quinter in Wayne County made an impact? Perhaps. Whatever the case, it had taken 13 years of careful deliberations at church conferences and councils for the Brethren in Christ to come to a common mind regarding the potential of a denominational paper.77

In 1851 when The Gospel Visitor had entered “the enterprising and entrepreneurial spirit of the times” to follow the evangelical lead and establish a church paper, it was with the explicit purpose of bringing unity to the church. Skeptics among the Brethren in Christ may well have observed how the Brethren church press had, in fact, given voice to the unrest expressed, most vocally, in South West Ohio. Indeed, vociferously divisive writings had contributed to the three-way split that rent the denomination in 1879. In Durnbaugh’s words, “[t]he columns of the papers gave those discontented with any aspect of the church a vehicle for expressing their grievances and attracting support for their causes.”78

The Davidson family was affected directly by the tensions that threatened unity in the Church of the Brethren, particularly because education was such a high priority in the Davidson household. One of his daughters described her father as “a great reader” whose self-education made him appear “to be a better educated man than he really was.”79 He and his family read widely. The Christian Herald, an American weekly that focused on evangelical concerns of the day, came regularly to their home, as did the New York Weekly Witness. “[A]safe family paper,” as he put it in his May 1888 editorial, theWitness“treated the various questions of the day, . . . generally on the right side of all moral issues.”80 Despite his lack of formal education, as these periodicals suggest, Henry was a thinker. His attraction to W. O. Baker, as he disclosed in an 1893 editorial, was at least in part for “’his reasoning powers which make his sermons ‘needed and appreciated.’”81

Census data and family lore indicate that at a time when only slightly over half of white children benefited from public education, the Davidson offspring attended school, some continuing as teachers. For instance, Emma would be remembered by the chronicler of Dekalb County where she settled after her marriage as having “received a splendid education.” She had taught school before her marriage to John Diehl, and in 1914 as owners of a 200-acre sheep farm the family moved “in the best social circles of the community where they have long been numbered among the best citizens.”82 Twins Henrietta and Henry also received good educations. The former’s daughter Pearl recalled later in life:

Mother was not only an educated person; she was extremely wise. Her children were not commanded, they were guided. The word “don’t” was not uttered. Every child felt his or her importance, and was aware of Mother’s great love for them and for her God.83

By 1881 Henry’s and Fannie’s natal church, the United Brethren in Christ, held 14 educational institutions, including a theological seminary. Even with the Brethren in Christ legislation passed in 1878 denying women the privilege of preaching, in the spirit of their more progressive co-religionists, Davidson and his friend Baker advocated publicly for women’s roles in the church.84 With the similarity in Church of the Brethren doctrine and practice to the Brethren in Christ, Ashland College held more appeal to the Davidsons than the United Brethren in Christ college at Otterbein. With her parents’ encouragement, 19-year-old Frances resigned from the teaching post she held for three years in Wayne County to follow W. O. Baker’s daughter Anna’s lead in enrolling at the newly-established Church of the Brethren College in Ashalnd, Ohio. They would be the first in the constituency to seek a college education.85

By the time Anna Baker Hixon, newly wed to professor Frank Hixon, graduated in 1882, Frances had withdrawn from school and was living in White Pigeon, Michigan with her family. Frances’s disillusionment had mounted as she observed the similarities with the Brethren in Christ diminish as the powerful progressive wing came to dominate; by 1881, as the Church of the Brethren fractured into three smaller groups, Frances had retreated to the warm familiarity of the Brethren in Christ community.86

With Frances’s return home, Henry Davidson sold his Ohio farm; with his five older children settled–four in Ohio, and Carrie in Abilene, Kansas–he moved Fannie and their eight children from their large brick home in Smithville.87 The family, now ranging from 23-year-old Lydia to Ida, just nine, re-configured itself in a frame homestead in White Pigeon, Michigan. Approaching 60, Henry devoted himself to mission on the American frontier, while he waited in anticipation for the fruition of his vision for a denominational paper.88 In the meantime, Frances continued her education at the Baptist College in nearby Kalamazoo; in 1884, three years after the family’s move to White Pigeon, Frances achieved a Master’s degree, the first in the denomination.89 Her literary skills would prove invaluable during the paper’s first year.

In Michigan, Henry continued the pattern set during the family’s Wayne County years. He preached regularly, his evangelistic ministry extending to Ohio and Indiana. He also travelled regularly to church meetings, including the annual General Conference held in various parts of the constituency. Ordained as bishop, he was known for his calm manner and was often called upon to moderate sessions. In her brief biography, Fannie Davidson, a granddaughter known to Visitor readers for her poetry, recalled:

on several occasions when the discussions as to various problems of the Church became overly warm Bishop Davidson would stand and say, “Now, Brethren. . . .” and then proceed to lay the foundation for a peaceable settlement of the discussion.

A particularly contentious conference earned him the moniker “Peacemaker of the Church.”90 As his daughter Frances would later recollect in a letter to her sister Ida, “when the council was in Indiana one of the Progressive Dunkards said Elder Davidson was the Henry Clay of the assembly.”91

On the home front, Henry was committed to finding Brethren in Christ spouses for at least some of his children. To be sure, the United Brethren in Christ mission endeavours had resulted in growth in Michigan, but it was Brethren in Christ connections that Henry sought;92 his evangelistic and preaching trips provided the opportunity. With the social limitations of the small Brethren in Christ presence in Michigan, the long-term relationship with Jacob and Sarah Brechbill in Auburn, Indiana, dating from their Stark County days, provided for marriages for twins Henry Jr. and Henrietta.

In September 1886, a wedding took place in the Davidson home. Henrietta married John Brechbill and the young couple immediately settled in DeKalb County in the log cabin on the property they obtained from his parents. By January 1887, Henry Jr. had married John’s sister Elizabeth. It would be up to Henrietta to teach her sociable husband the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic, so they could succeed in their farm enterprise. A few years later John would build a brick home large enough to accommodate their growing family. Meanwhile, Henry Jr. and Elizabeth pioneered in Kansas, farming the 160 acres that his father had claimed on the basis of the 1862 Homestead Act. The increased opportunities that the late nineteenth-century afforded women allowed for financial support for the family. Frances and three of her sisters, who were among the 13 percent of women in their generation who remained single in that generation, taught school; they also ran the household in Fannie’s stead as her cancer progressed.93

It must have been a difficult period for Henry Davidson, his friend W. O. Baker, and the small handful who supported the idea of a church paper. Discussion languished for years, only to be revived and opposed again. After 13 years of careful consideration, at the landmark 1887 General Conference held on Cyrus Lenhart’s Pennsylvania farm, the church responded positively to Michigan district’s petitions: the Brethren in Christ were finally ready to risk a new mode of communication. A committee of five, with Davidson and Baker at the helm, were given a four-year mandate to test the waters. Henry enthusiastically took on the mantle of first editor and in just over three months, he had the first issue to press. The words, “Devoted to the spread of evangelical truths and the unity of the church,” as proclaimed the Evangelical Visitor‘s mast-head, described his vision.

From White Pigeon to Abilene, Kansas

Fifty years later, in the gold embossed covered anniversary issue of the Evangelical Visitor, one of Fannie’s namesake granddaughters lovingly sketched the first years of production, as it was inscribed in family memory:

. . . remember this was undertaken in horse and buggy days and at a time when mail-carriers and telephones were unknown. A daughter says, “All the material for publication was first sent to our home and we prepared it for the printers, then it was mailed to the printer and set, then he returned the pages for proof-reading, we proof-read them and then they were mailed to the printer again.”94

Frances played a large part in the production of the first issues. She proofread, did mailings, and, according to historian Morris Sider, “rewrote most of the scarcely readable articles that the well-meaning but poorly educated Brethren submitted.”95 As Wittlinger has noted, “Miss Davidson slyly observed that some contributors may have had considerably (sic) difficulty recognizing what they had written.”96

Initially, Henry sent the material to Elkhart, Indiana, not far from where Henrietta had settled, for publishing; later he found a printer that was able to offer a better price near W. O. Baker’s home in Ashland, Ohio. All of this required much travel by rail, until at the church’s request the family moved once more, this time to Abilene, Kansas. Here far removed from the centre, and with the flow of Brethren in Christ who had joined the westward immigration, there was a broader base of support to help them feel connected. With the impetus to establish institutions in a land still in flux, the Brethren in Christ would establish their own printing house.97

By the Visitor’s first anniversary, Frances had accepted the invitation of Ashland College’s former President S. Z. Sharp to teach at the school the Church of the Brethren had invited him to start in McPherson, Kansas. In September 1888, Frances cast her lot with the increasing numbers of Brethren in Christ who were responding to the boom colonizing the west. Her affiliation with MacPherson College brought her within 40 miles of Abilene, where Henry had set up Henry Jr. some months earlier.98 On Henry’s and Fannie’s part, the impact of this double loss can be seen in the distress call in the guise of an advertisement in the Visitor six months later:

“Farm for Sale”

I desire to sell my farm of 145 acres. It is a beautiful home, good building, near to R.R., level land, easy to cultivate, and in a healthy country. It is necessary that I should sell the farm, or give the publication of the Evangelical Visitorinto other hands. For particulars address the undersigned.

Henry Davidson,

White Pidgeon, Mich.99

By November, the “store of good and suitable matter” for publication had become “nearly exhausted.” Readers had responded well to his earlier request for material that would spell out various points of doctrine. Now, as he indicated to Visitor readers, he could fill out pages by drawing from other publications such as the United Brethren Telescope and the Church of the Brethren Gospel Messenger, both of which he had recommended to readers a few months earlier.100 But the point of publishing a denominational paper was to hear the voices and perspectives of the Brethren in Christ themselves: “We do not wish to dictate,” he apologized, “but . . . so far as refers to the ordinances we are pretty well supplied. . . .” Encouraging theological reflection, he requested potential writers to submit pieces that would promote unity, not dissension and division. “There is no subject so inexhaustible as the ‘attributes of God’,” he declared:

. . . while much that is said . . on this subject is probably speculation, yet it will undoubtedly do us all good to dwell largely on his loving kindness shown toward the human family; but whatever the subject is that you may desire to write on, let us hear from you soon.101

Davidson believed that a typewriter would help production, but the negative reaction to his well-meaning featuring of the Odell Typewriter Company in January 1891, with its promise of a typewriter in exchange for advertising was immediate, and strong. With his survey of a variety of papers, Henry would have seen the shift in the previous decades, where advertising had reached equal proportions to editorial material.102 His sensitivity to the denomination’s standards on such publicity made his task more difficult. As this minor controversy illustrates, and Wittlinger has phrased so well, “[o]nly a man with common sense, fortitude, and spiritual dedication could have coped with the many problems that arose during the early years of the Visitor. Henry Davidson proved to be such a man.”103

It must have been a long four years for Henry and his family. In May 1891 when the long anticipated referendum arrived, Henry was 68 years old, with Fannie, now 60, continuing to weaken with cancer. Having Lydia, Emma, Albert, and Ida still at home must have eased things on the home front. Wittlinger has discussed at length the “four-year referendum” which the church had agreed to hold before committing to the paper. General Conference of 1891 assembled at Mastersonville meetinghouse in Lancaster County, where the opposition to the Visitor was the strongest. The gathering was quite likely the largest in the denomination’s history. A spirited debate, where emotions ran high, gave no indication which way the vote would come down. The mood was expectant, if subdued, as ballots were cast; although the result was uncomfortably close, in his steady way, Henry saw the potential for the future, and accepted the challenge of continuing his mission. He left that conference of 1891 committed to continuing to spread “evangelical truths and the unity of the church” through his work as editor of the Visitor. ((Wittlinger, Quest, 263-64; The Editor, “When… Why… How…,” Evangelical Visitor, August 28-29, 1937, 7; Eli M. Engle, “Personal Reminiscences of the Introduction of the Evangelical Visitor,” Evangelical Visitor, August 28-29, 1937, 29; Brickner, “One of God’s Avenues,” 323-24; and Davidson,“The Annual Conference,” Evangelical Visitor, June 1, 1891, 168.))

Two months later, the family was re-settled in Abilene, Kansas. Only Henry’s brief word of apology in the July 15 issue gave readers a glimpse of what this upheaval meant for him and his family: “the Visitor is a little late this month, which is due to the hindrances that came through the change of residence, and the extra labor connected with changing from one place to another has interfered with our editorial work.” As they accompanied their worldly possessions on a train heading west, the Davidsons joined the flood of immigrants who were benefiting from the 1887 Dawes Act that destroyed indigenous traditional communal agriculture by dividing it into farms. The contemporary view—that resettlement was essential to the church’s mission—bolstered their vision. Once re-settled, Henry quickly got back on task, ensuring readers in his practical, calm way, “in a short time we expect to be going forward as usual.”104

For Henry, the “harmony and good-will” that had “prevailed” at the Masterson meeting house was key to his ministry, as his appointment to one of the three moderator positions at most conferences from this time until his death in 1903 underscores.105 Under his editorship, the Visitor strengthened the connection for the geographically diverse community. In the larger society, the press had taken on the significant function of building diverse and far-flung communities, in Nord’s words, as “conversation, connection, and common action.” For people far from the centre, the paper shortened the great distances that separated family and friends, giving them some experience of home, as the very name Visitor evokes.106

Under Davidson’s leadership, the paper provided a forum for teaching with its doctrinal expositions; it reached shut-ins and folks far from the centre with sermons and evangelical exhortations on a large range of topics including the ordinances of baptism, communion and foot washing, peace and nonresistance, and separation from the world. Morals told through story and poetry provided a literary component, often explicitly aimed at youth. Detailed reminiscences created historical memory. And for many, opportunities to write, and to read the experiences of others, provided the sense of home that papers had long given a mobile American population, many of whom found themselves far from family and community.107

Henry’s editorial wisdom helped the Visitor quietly bring the Brethren in Christ into the evangelical mood of the time. Pieces selected from other papers subtly introduced the denomination to the large communication networks that were key to giving the nineteenth century evangelical movement shape.108 More explicitly, the paper gave expression to Davidson’s vision of moving the denomination out from its insulated farm communities to broaden the denominational perspective through education and mission.

Frances Davidson’s two-part piece on “Education and the Prophets” that appeared amidst experience stories and doctrinal expositions during the Visitor’s first year heralded her departure for McPherson College, and set the tone for the paper’s educational mission. Through thoughtful discussion taking readers from the Old Testament Schools of the Prophets, to Jesus’ preparation for his ministry, to Paul’s instruction of Timothy, she challenged doubtful readers to consider the benefits of an education well-used in pursuing “the cause of our Blessed Redeemer.”109

From the outset, Henry’s heart for mission was reflected in articles written by members who shared his concern. Strategies ranged from Indian mission, to moving even further west, to sending workers into areas where the denomination had not yet reached. The underlying goal was to help readers look beyond their comfortable farm communities.110 His June 1891 report on the ground-breaking conference decision to continue the paper, for instance, highlighted pieces from those already engaged in mission that, in his words, “cheered the hearts of the friends of mission work.” As he put it, the steady stream of informational pieces attempted to assuage the “grief” in “the great want of laborers in the vineyard of the Lord,” and to challenge the church to proclaim the gospel at home and overseas.111

Meanwhile, the Kansas family grew smaller. Shortly after the senior Davidsons came west, Henry Jr. and Elizabeth re-joined Henrietta and John in Indiana, leaving a tiny grave on the Kansas prairie.112 Emma married John Diehl, making it three Davidson siblings who would raise their families in DeKalb County. Both Henry’s and Fannie’s legacies would continue in that community, with twins Henry and Henrietta each naming a daughter Fannie.113 These changes transpired as pioneers to the west struggled with conditions brought on by drought. At McPherson, declining student numbers would see Frances resign from her teaching position; by fall 1894, she had returned home to help Lydia and Ida care for their mother during her last days.114

Barely two and a half years after their move to Kansas, on October 14, 1894, Fannie Rice Davidson succumbed to the cancer that had plagued her for 30 years. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich has found that nineteenth-century women “became legitimately visible in only three ways. They married, they gave birth, they died.”115 As we have seen, what we know about Fannie’s life illustrates this truism. Her obituary published in the Visitor with “Our Dead” in November 1894, vividly depicts the last days and final moments of her life. Minister Samuel Zook described her:

she met the final change in a glorious triumph of faith in her Redeemer. The writer of this notice frequently visited her during her affliction and always found her resigned to the will of the Lord; but the last visit a few days before her death was especially encouraging. While in conversation, she all at once cast her eyes upward and shouted while clapping her hands: ‘Oh, praise the Lord – Glory! – Oh, I am so happy in the Lord.’ She continued in that ecstasy of mind until she became unconscious, and she calmly and peacefully passed away.

Zook continued, noting that local businesses closed their doors in her honour and that “the Brethren meeting house . . . was crowded to its utmost capacity, and many that were there could not find admittance.”116

Anyone who has accompanied a loved one in the last stages of cancer will know something of the anguish that Frances felt. Close to the end, she had shouldered the expense required to take her mother on an excursion to the Rockies, but there was nothing more she or anyone else could do. As she lamented in her journal, without her mother’s presence, home was no more:

Now I can do no more for her and my eyes overflow as I think of the broken home. What is home without a mother? No home! None! True dear father still lives and I do think of him, but the link that keeps the family together is broken.117

From Kansas, east again

The family would scatter still further, as Fannie’s death propelled Lydia and Frances to became feet for their father’s vision of mission. At the time of her mother’s death, Lydia was nearly 40 and still single. Testing her father’s belief shaped by his own United Brethren background that women had a particular capacity for mission, Lydia would relocate to Chicago; there she would work for a time with Sarah Bert at the recently established Brethren in Christ mission.118 Frances’s response to the invitation of Fannie’s brother Cyrus to come to University of Chicago for studies would set the stage for the awakening that would precipitate her call to overseas mission.119

In spring 1896, Henry suffered another blow. He was unable to understand why the opposition to a church paper, voiced most loudly in far away Pennsylvania, removed him from his role as editor. In the weeks leading up to that fateful decision, testimonials pouring into his office, he had devoted no less than six articles reminding the church of “The Blessedness of Christian Union.”120 When the General Conference that convened that year in Greencastle, Pennsylvania appointed a new Board of Publication, Henry was given only four months more to serve as editor of the Visitor. ((Wittlinger, Quest, 265; Davidson, Evangelical Visitor, October 1, 1896, 296.))

Well past the biblical three score and ten, widowed, stripped of his editorial privileges, and Lydia’s and Ida’s marriages leaving him alone at the Davidson home in Abilene, Henry would re-invent himself once more. Taking seriously the responsibility conference did allow him as chair of the committee appointed “to formulate a plan for Foreign Mission work,” Henry arranged to return east. His marriage to Kate Brenneman, two decades his junior, would give him a practical outlet for mission. During his final years of ministry, along with the responsibilities of bishop bestowed by the West Milton Brethren in Christ Church in Southwestern Ohio, Henry explored the potential of mission, both at home and overseas.121

Having come full circle, he would live out his final years in Pennsylvania, in the heart of the Brethren in Christ community. He shared with his new wife a vision of mission that served the aging in the Brethren in Christ community, with their work at Messiah Home for the Aged [now Messiah Lifeways] that she had co-founded in Harrisburg. His legacy also reached far beyond the cradle of the denomination. Just months after his marriage, his daughter Frances responded to a dramatic call to volunteer for overseas mission. Expressing his fear that she had failed to count the cost, he reluctantly gave his permission: “It is painful to say yes, but how can I say no?”122 The cost implied in that “yes” illustrates his reputation, in Brickner’s words, of being “[o]ne of the strongest mission advocates.”123 Indeed, on his death six years later, Frances grieved the loss of one who was more than beloved father. As she expressed in a letter to her family, “I have written him everything.” Indeed, she declared, a recent 19-page letter from him confirmed that he knew better than most the particular needs of those working in overseas mission.124

Known as “The Peacemaker” for his calm handling of discussion, Henry Davidson served as moderator of international conference sessions up until his death in 1903.125 With vision, openness to change, and his willingness to accept the personal sacrifices that such leadership demands, Henry Davidson served the Brethren in Christ as minister and bishop (or elder) for over 50 years. He left a heritage of a space where a far-flung people could encourage one another, and gain the benefits of community through writing and reading the words of others. He aided the process of putting doctrine and belief in print, and he promoted a vision that created a more unified North American denomination, one that gained confidence as it embraced the tools of evangelicalism, especially education and mission. The words of George Detwiler, editor of the Visitor at the time of Henry Davidson’s death, said it well:

He had his share of sorrows and hardships and struggles. We need not think, occupying the prominent place he did, that he had the praise of everybody. The Apostle Paul makes use of the expression, “men of like passions” and we know that Elder Davidson did not claim for himself perfection. He had his weaknesses and no doubt made many mistakes, (and who would undertake to throw the first stone!) but we believe that throughout his long career there was an honest purpose to serve the Master whose servant he had become, and to the extent of his ability, given him by God, to work for the unity, and prosperity of the church. He now rests from his labors.126

Henry Davidson also left a legacy as a father and husband. In her letter to the sisters still living in Kansas, Frances expressed the grief left on the departure of a much-loved father:

His was truly a life of activity in the service of the Master. From our earliest recollection I can remember his prayers, and his sermons always moved me more than those of any one else before I was converted and wherever the church or work called, he was ready to go, bad weather could not keep him from filling his appointments, and then for nine years was the laborious task of editing the Visitor and he was chiefly instrumental in getting it started. Then in his later years was deeply interested in the mission work and all his life active in the councils . . . since I was in the mission work and he President of the Board as well as my father, I have written him everything and consulted him about everything and I can never more say “I must write and ask Father about that.” He seemed to understand the needs of the work so well for one so far away. . . .127

Assumed but unspoken was the support of his wives, none more than his partner of nearly 40 years, Fannie Rice Davidson. Her labour and contributions to his ministry are summed up in Frances’s lament on her mother’s death: “what is a home without a mother? No home.” Few words survive that would help today’s reader understand Fannie’s part in Henry’s ministry, but we can read something of Fannie’s character from what we know of her daughters. We can be sure that Fannie’s intelligence, wisdom, and strength, passed on to her children, not least her namesake H. Frances Davidson, were crucial to the success of Henry’s ministry and legacy.128 Although few of their descendants remain within the Brethren in Christ denomination, the Davidson vision that brought the denomination into the nineteenth-century evangelical world of communication, education and global mission has inspired the church for well over a century.

- In 1895, Ida Davidson had married Martin L. Hoffman, a Brethren in Christ minister who ran a large creamery plant in Abilene. See Earl D. Brechbill, The Ancestry of John and Henrietta Davidson Brechbill: A Historical Narrative (Greencastle, PA: printed by author, 1972), 58; History of DeKalb County, Indiana (Indianapolis, IN: Bowen and Co., 1914), 732, [↩]

- In 1896, Lydia Davidson had married Joseph M. Brewer. They farmed just outside of Osage City, near Abilene, Kansas: ”Married,” Evangelical Visitor, October 1, 1896, 304; see also Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 56. [↩]

- In 1875, Carrie (Caroline) Davidson had married Jacob Landis, a hardware merchant in Abilene: Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 56; see also History of DeKalb County, 732; “D. Landis Family Tree,” Ancestry.ca, accessed June 7, 2018, https://www.ancestry.ca/family-tree/person/tree/106889329/person/370055847787/story. [↩]

- Susan J. Rosowski, Birthing a Nation: Gender, Creativity, and the West in American Literature (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 56. [↩]

- H. Frances Davidson to Martin and Ida Hoffman, May 3, 1903, MG 40-1.6, housed in Brethren in Christ Historical Library and Archives, Mechanicsburg, PA. [↩]

- Charlotte Gray has addressed the phenomenon of letters evoking a particular moment in time for contemporary reader: Canada: A Portrait in Letters (Toronto: Doubleday, 2003), 1, 3; see also David M. Henkin, The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 3-4, 93, 147 and Virginia Walcott Beauchamp, “Letters as Literature: The Prestons of Baltimore,” in Women’s Personal Narratives, ed. Leonore Hoffman and Margaret Culley (New York: Modern Language Arts of America, 1985), 37-38. [↩]

- H. Frances Davidson, personal diary, March 2, 1895, Hannah Frances Davidson Diaries (hereafter HFD Diaries) 1, Brethren in Christ Historical Library and Archives, http://messiaharchives.pastperfectonline.com/archive/D7FCD1A1-ABA4-4088-94C8-059638202176; and Lucille Marr, “Conflict, Confession, and Conversion: H. Frances Davidson’s Call to Brethren in Christ Missions,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 9, no. 3 (December 2017): 345. [↩]

- With the help of the following people, the author researched and found Henry Davidson’s gravesite in Wooster, Ohio: E. Morris Sider and Glen Pierce, emails to author, summer 2013; Susie Holderfield, telephone conversation with author, July 23, 2013; and the helpful staff of the Wayne County Historical Library, Wooster, Ohio who provided a map of the Wooster cemetery, http://www.wcpl.info/genealogy/index.php/Main_Page. Mary had been widowed in early February 1893: “Peace to his Ashes,” Wooster Daily Republican,February 6, 1893), 3. The attempt to keep their business enterprise Hotel Yoder running had been thwarted with the sudden death of their 20-year-old son Isaiah a year and a half later, just weeks before Fannie Rice Davidson succumbed in October 1894: courtesy of Elaine Fletty, Wayne County Public Library, Genealogy and Public History Department, Wooster, OH; “Our Dead,” Evangelical Visitor, November 1, 1894, 336. [↩]

- Mary was born in November 1844; she married Christian Yoder December 1866 and died in Ohio in March 1930; Sarah was born in December 1846; she married Henry Coup in 1865 and they would live out their lives in Ohio; Sarah died in September 1923; William was born in December 1848 and married Margaret Miller in November 1874; they farmed in Ohio until his death in May 1930; Isaiah was born fall or winter 1854-55; in 1878 he married Ellen Dohner and held the post of Principal of Barberton High School in Ohio for many years; he died in 1935: Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 52, 55-56; and History of DeKalb County, 732. [↩]

- Lydia was born in February 1857 and died June 1923; Rebecca was born in July 1858; she married Warren Dohner in February 1881 and died in August 1916; Emma was born in June 1862; she married John Diehl in November 1891 and died in May 1940; Henry Jr. was born in March 1865; he married Elizabeth Brechbill in January 1887 and died August 1938; Henrietta was born in March 1865; she married John Brechbill in January 1887 and died in June 1949: Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 56-59; History of DeKalb County, 732. George Albert was born in September 1872 and died in November 1952; he married and had two children: California, Death Index, 1940-1997, Ancestry.com. [↩]

- “One of God’s Avenues of Progress: Exploring the Outcomes of the Evangelical Visitor,” Brethren in Christ History and Life 40, no. 3 (December 2017): 324. [↩]

- I have relied heavily on the Davidson history compiled by Ida Davidson Hoffman’s son Paul as recorded by Henry and Fannie Davidson’s great-grandson Earl Brechbill in “Ancestry.” [↩]

- See Mark A. Noll, David Beggington, and George A. Rawlyk, eds.,The British Isles, and Beyond, 1700-1990(New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 5-6, for their emphasis on the significance of evangelicalism to the history of Christianity. [↩]

- Lee S. J. Kleinberg, Women in the United States 1830-1945 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1999), 5, for her discussion of “the grand forces shaping American life,” including “the westward movement.” [↩]

- Kleinberg, Women in the United States, 8. [↩]

- Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 53, 55; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Record of Appointment of Postmasters, 1832-September 30, 1971, roll #113, Archive Publication #M841, Ancestry.ca. [↩]

- Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 52. [↩]

- William Sweet, Religion in Colonial America (New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1965), 250-51. [↩]

- Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 52; Sydney Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 248, 441; Raymond Waldfogel, “The Church Takes a Name,” in Trials and Triumphs: History of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ, ed. Paul R. Fetters (Huntingdon, IN: Church of the United Brethren in Christ Department of Church Services, 1984), 88. [↩]

- Charles Hockensmith, The Mill Stone Industry: a Summary of Research on Quarries and Producers in the United States, Europe and Elsewhere(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), 13-14; 44-45. [↩]

- “Young Family Tree,” Ancestry.com. [↩]

- Brechbill has her birth in 1835: see “Ancestry,” 56; according to the 1850 United States Federal Census, she was born in 1831: Ancestry.ca, http://person.ancestry.ca/tree/84863155/person/40517204644/facts; Fannie Rice carried the name of her mother Frances Strickler Rice (1802-1870) and grandmother Frances Stewart Strickler (1772-1838): Find A Grave Memorial #95499749, created by Susan Matthews, Ancestry.com, accessed by permission of Mark Myers, August 25, 2016. [↩]

- Frances Strickler Rice received $1000.00 at the time of her father Henry’s death: Ancestry..com; in “Ancestry,” 56, Brechbill cites a letter from Henry Davidson to his Craft in-laws where he observed that Fannie came from a family that was well off. [↩]

- Sweet,Religion in Colonial America, 252-53; Carlton O. Wittlinger also referred to this phenomenon: Quest for Piety and Obedience: The Story of the Brethren in Christ (Nappanee, IN: Evangel Press, 1978), 12. [↩]

- Mark Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids, MI.: Eerdmans Press, 1994), 73; Wittlinger, Quest, 19-20, 23-25; Ahlstrom, Religious History, 249-50; Galen Hochstetler, Celebrating 150 Years of Paradise Church of the Brethren, 1841-1991(Smithville, OH: Bicentennial Committee, 1976), 1; Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 56; and Donald F. Durnbaugh, Fruit of the Vine: A History of the Brethren, 1708–1995 (Elgin, IL: Brethren Press, 1997), 317. [↩]

- Wittlinger, Quest, 11. [↩]

- Fetters, Trials and Triumphs, 45-46.; Mary Lou Funk, “The Best and the Worst of Times,” in Fetters, 198; Paul A. Graham, “The Beginnings,” in Fetters, 60, 76-77; and Sweet, Religion in Colonial America, 323. [↩]

- Religious Telescope, January 1853, cited in Funk, “The Best and the Worst,” 177. [↩]

- Funk, “The Best and the Worst,” 183. [↩]

- Durnbaugh, Fruit of the Vine, 317-18. [↩]

- M.J. Heisey, Peace and Persistence: Tracing the Brethren in Christ Peace Witness through Three Generations(Kent, OH: Kent University Press, 2003), 18; Elizabeth Jane Errington, Wives and Mothers, School Mistresses and Scullery Maids: Working Women in Upper Canada, 1790-1840 (Kingston, ON and Montreal, QC: McGill Queen’s University Press, 1995), 22, 210; Kleinberg, Women in the United States, 60-61; and Marguerite Van Die, “The Double Vision: Evangelical Piety as Derivative and Indigenous in Victorian English Canada,” in Noll et al., Evangelicalism, 260-61. [↩]

- Funk, “The Best and the Worst,” 176; see also180, 198 and Waldfogel, “The Church takes a Name,” 87-88. [↩]

- James G. Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish: A Social History (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1962), 199; see also George Dallas Albert, County of Westmoreland, Pennsylvania, with Biographical Sketches of Any of the Pioneers and Prominent Men(Philadelphia: L. H. Everts and Co., 1882), 44, accessed June 11, 2018, https://archive.org/details/HistoryOfTheCountyOfWestmorelandPennsylvaniaWithBiographicalSketches. [↩]

- Wikipedia, “Fayette County, Pennsylvania” accessed May 18, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fayette_County_Pennsylvania#History; “ Brownsville Northside Historic District,” 1997-2015, The Gombach Group, accessed August 5, 2016, http://www.livingplaces.com/PA/Fayette_County/Brownsville_Borough/Brownsville_Northside_Historic_District.html, (Living Places information is deemed reliable but not guaranteed); Albert, County of Westmoreland, 44; and Franklin Ellis, History of Fayette County, Pennsylvania: with Biographical Sketches of Many of its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1882),13, accessed May 14, 2018, https://archive.org/details/historyoffayette00elli. [↩]

- Hockensmith, Millstone Industry, 207; see also 208-09; Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 53. [↩]

- Brechbill, “Ancestry,” 53; Ellis, History of Fayette County, 425. [↩]