The Bible conference was introduced to the Brethren in Christ by the church school in Grantham [now Messiah College] in the first year of its existence (1910). The event became so popular that virtually all areas of the church adopted it. These one- or two-day events occurred in the winter months, and usually in connection with revival meetings. The conferences emphasized doctrinal preaching, and provided a good platform for popular subjects such as prophecy. They also became additional occasions for fellowship among members from various congregations, the fellowship being heightened by eating meals together throughout the event. . . . The first half of the twentieth century was the heyday of the Bible conference. Gradually it gave way to other events designed to achieve the same ends, not least the holiness camps [such as Roxbury and Memorial Holiness].

The Bible conference was an integral part of the revival meeting in the earlier years of Messiah College. Placed at the end of the revival, the conference was a concluding or climaxing feature. Originally 10 days in length, in 1920 they were reduced to eight and in 1930 to four. Eventually a pattern, not strictly followed, emerged: an education program on Thursday, a youth program on Saturday (including special music by college music groups), and a missions program on Sunday. To end the Bible conference with a missions program, always with a call for young people to present themselves for service, was deliberate, reflecting the missions orientation of the school.

But the Bible conference offered an even wider variety of themes and sermons than this has suggested. The Bulletin for January 1918, for example, announced that the coming conference was “intended to meet the need of both the ministry and the laity . . . [and] to arrange for questions of vital interest to the church as applied to everyday conditions.” The program listings show that the intention was carried out. . . .

The question and answer periods built into each Bible conference were most certainly among the most valuable features of the program. “A conference implies discussion or an interchange of opinion,” the January 1922 Bulletin explained. “With the inherent limitations of the human mind it is too much to expect that we will all see alike, but if the spirit of love and unity prevails, intelligent discussions will tend toward unity of belief and practice. The past conferences have been marked by kindly forbearance with those who differed in interpretations.” The words, obviously intended to be euphemistic, were a sure sign that the discussions were lively, entirely fitting on a college campus.

The speakers may have been the greatest attraction of the Bible conferences. At no other place except General Conference could such a stellar display of Brethren in Christ leaders be heard. They included pulpiteers such as Solomon (S. G.) Engle of Philadelphia; J. R. Zook of Des Moines; Lafayette Shoalts of Ontario, Canada; Bishop C. N. Hostetter, Sr., of Lancaster County (Manor-Pequea District), and, beginning in the later 1920s, his son C. N. Hostetter, Jr. Also gracing the pulpit were thinkers and effective Bible teachers such as Eli Engle, Abner Martin, H. K. Kreider, and, of course, the college professors. Missionaries on furlough provided a certain fitting yet exotic touch to the occasion.

No wonder then that conferences at the college became the leading event of the year among the Brethren in Christ in Pennsylvania [and elsewhere]. . . . The conferences also drew in some local people from other denominations. The Bible conference had “grown so large and the interest so great,” the Evangelical Visitor noted in 1921, “that all look forward to the time when it shall start and are already informed before any information could be given through our paper.” People were getting into the habit, the paper continued, of laying everything aside and spending the whole week at Grantham.

They came in cars, and, especially in the earlier years, in trains. Even the five trains a day in each direction became insufficient, particularly in cases where transfers from other lines had to be made. . . .

Such crowds taxed the eating and lodging resources of the college. Visitors slept in the homes of the community (at least 100-200 people each year, a 1919 report claimed), in Treona across the creek from the college, and on bedroom and classroom floors in Old Main. In the latter two areas, guests slept on bedding and mattresses that Mrs. Enos (Barbara) Hess and other Grantham women collected each year from Brethren in Christ homes in Mechanicsburg and the surrounding area.

Lodging came free; meals until 1918 cost 20 cents each, or 50 cents a day, with a slight increase in later years. Large crowds meant eating in relays. Students, assigned to clean and set tables, wash and dry dishes, managed their work so well, the Clarion once boasted, that in ten minutes they could clear and reset the tables for the next group of diners. They also provided special music during the meals, thus keeping down the noise and adding a tone of spirituality even to the eating. . . .

Bible conferences elsewhere were not as ambitious as those at Grantham. Yet they were of the same spirit. Despite the doctrinal orientation of the Bible conferences, even young people (including me) could enjoy these events, undoubtedly, in part, because some of the ministers were interesting speakers (a few verged on being entertainers), and, of course, because of the splendid meals that accompanied the program.

Morris Sider is the author and editor of numerous books about Brethren in Christ history and its people. He also served for many years as executive director of the Brethren in Christ Historical Society. This article is excerpted from his recent book, Stories and Scenes from a Brethren in Christ Heritage (Brethren in Christ Historical Society, 2018). All members of the Society received a free copy last year, and additional copies are available for sale.

E. Morris Sider’s recently released book, Be In Christ: A Canadian Church Engages Heritage And Change, is a revised and updated version of his The Brethren in Christ in Canada: Two Hundred Years Of Tradition and Change, published in 1988. The new, nearly 500-page book contains 85 photographs, numerous stories, descriptions of significant changes in the last 30 years, and an improved organizational structure.

E. Morris Sider’s recently released book, Be In Christ: A Canadian Church Engages Heritage And Change, is a revised and updated version of his The Brethren in Christ in Canada: Two Hundred Years Of Tradition and Change, published in 1988. The new, nearly 500-page book contains 85 photographs, numerous stories, descriptions of significant changes in the last 30 years, and an improved organizational structure.

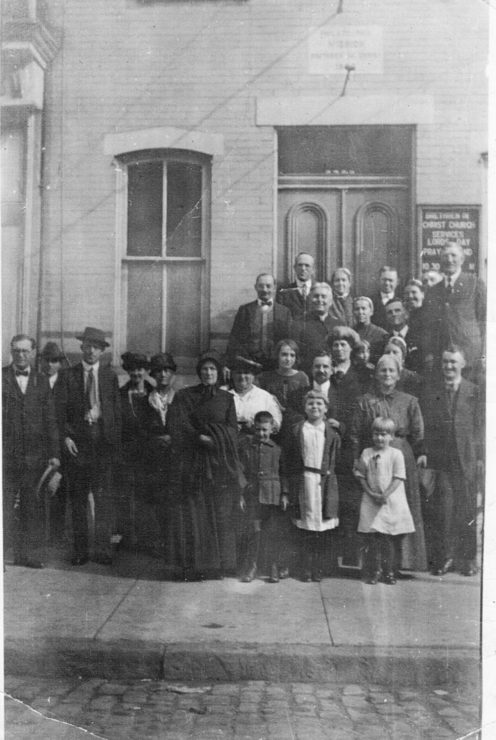

On October 6, 2019, the Bethel congregation in Virginia will be celebrating the centennial of the beginning of Brethren in Christ work in Virginia. During the early years, groups of persons from Pennsylvania traveled to Virginia to offer various types of assistance. This undated photo shows one such work team from central Pennsylvania. The caption penciled on the back of the photo reads:

On October 6, 2019, the Bethel congregation in Virginia will be celebrating the centennial of the beginning of Brethren in Christ work in Virginia. During the early years, groups of persons from Pennsylvania traveled to Virginia to offer various types of assistance. This undated photo shows one such work team from central Pennsylvania. The caption penciled on the back of the photo reads: