by Alice French Andrews

Grace Edna Ramsdill Adams died of the Spanish flu in Mason, Michigan on January 4, 1919. She was only 28 years old, and she was expecting her first baby. Grace was the much-loved half-sister of my grandmother Mary Jane (May) Rose Schneider, which makes Grace my half great-aunt. (Hereafter I will drop the “half.”) Grace’s family had experienced several tragedies before her death, but it is hard to know if those experiences made her family better able, or less able, to cope with their grief and loss when Grace and her unborn child both died.

I will start Grace’s story with her mother, who was born Charlotte (Lottie) Bowdish in 1856 in Michigan. Lottie was my great-grandmother and a redhead. Sadly, Lottie’s childhood was overshadowed by the Civil War. Not only did her father, William Ferdinand (Ferd) Bowdish, enlist in the Michigan infantry, but so did four of his brothers. One of these Bowdish uncles of Lottie suffered a foot injury, one lost an arm in the second Battle of the Wilderness, another lost his life from injuries in that same battle, and the fourth uncle absconded from the army. On Lottie’s mother’s side of the family, her mother’s only brother was a nurse in the Civil War, and he died of illness at the end of the war before reaching home. Ferd Bowdish himself was shot in a battle in 1864, but the ball happened to strike his pocket where he carried his diary and a tintype of his family, so, although he was knocked flat from the force of the bullet’s impact, he was not fatally injured. Later in 1864, Ferd was taken prisoner and spent months in a Confederate prison camp in Salisbury, NC. Ferd lived to see the end of the Civil War and made it back home to his family, but his health had been ruined, and he died in 1867 when Lottie was just 10 years old.

Lottie’s widowed mother remarried in 1874 when Lottie was 17 years old, so Lottie knew what it was like to have a stepfather. In her diary she referred to him as “—” which might be an indication of Lottie’s ambivalence toward him joining her family, or at least ambivalence about what to call him in writing.

Lottie herself became a bride in 1876 when she was 19, and her groom, William (Will) Taylor Rose, was just 18 years old. They were farmers. In 1878 a baby girl, Nellie, was born to them, and at the beginning of 1881 they were expecting another child, but Will never got to see his second baby girl because he died unexpectedly on January 4, and baby May was not born until March. (Will almost certainly died on January 4, but one record says his date of death was January 2.) The cause of his death was Will being accidentally shot in the head by a hunting companion. He did not die instantly, but was taken to his home, where Lottie was with him when he died. It must have seemed ironic to Lottie that her 23-year-old husband died of a gunshot wound during peacetime. Will was buried less than four miles from where the Carland- Zion Brethren in Christ Church would be founded in 1890.

Lottie was a 24-year-old widow, and she moved back to her mother and stepfather’s home, along with her small daughter Nellie, to await the birth of her second child. At birth. baby May had a scalp lesion of some missing skin with underlying underdeveloped bone. People (mistakenly) thought this lesion was caused by the emotional trauma Lottie went through by her husband being shot in the head while she was pregnant. There were concerns that baby May might grow up to be, in today’s terminology, intellectually challenged, but the diagnosis of the lesion was probably aplasia cutis congenita, which is rarely associated with brain abnormality. The lesion healed and May grew and developed well.

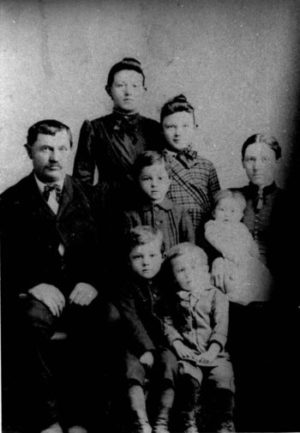

In 1883 Lottie remarried to Van Ranslaer (Rance) Ramsdill, a childless widower who was 11 years older than Lottie. He himself was a Civil War veteran, having fought with a Michigan cavalry unit. After their wedding, three sons were born in quick succession, and then baby Grace was born in 1890. Rance was said to have bouts of “insanity” which sometimes landed him in an asylum. Today he likely would be evaluated for post-traumatic stress disorder. Grace was only six years old when her father died, making Lottie a widow again, this time with six children. Nellie, the oldest child, got a housekeeping job and was treated like an adopted daughter in that household. May helped her mother with the four younger children. Lottie was capable of doing outside farm work herself, but she had to hire farmhands to help her. Then in 1898, when Lottie was 41 years old, she married one of her farmhands, Sid Coulston. Sid was 18 years younger than Lottie—perhaps Lottie wanted to be sure her third husband would outlive her (which he did). Lottie had a pregnancy with Sid, but the baby died.

In 1899 Nellie married, and she and her husband had a baby boy, but then Nellie’s 25-year-old husband died from typhoid fever in September of 1901. In October of 1901, 20-year-old May married Henry Schneider, Jr., future Brethren in Christ bishop and evangelist. (Fortunately Henry did not die young as his father-in-law and brother-in-law had –he lived to be 92 years old.) May and Henry’s first child was born in 1904. They were having difficulty deciding on a name for their baby girl until May’s sister Grace suggested “Gladys,” which name was agreed upon. Gladys would become my mother, and it was thought her name suited her well because she grew so many beautiful “glads” (gladioli) in her garden.

Of all her aunts, Gladys liked Aunt Grace the best, probably because Grace was the youngest, being only 14 years old when Gladys was born. For the first few years of Gladys’s life on a farm outside Carland, Aunt Grace lived nearby, and they saw each other often.

Then Aunt Grace moved, along with her mother (Lottie) and stepfather (Sid), away from Carland to the town of Mason. In 1909 Grace started working at the post office in Mason. She met a rural mail carrier named Roy W. Adams, and they married in 1916.

When Gladys was old enough, she and her aunt Grace wrote letters to each other. For example, on October 29, 1917, 27-year-old Grace wrote a letter from Mason to 13-year-old Gladys, now living outside Merrill, Michigan. Grace told of a local rail-car crash, of Ma and Sid coming for dinner, and of preparing a paper on Alaskan mines for the Mason Tourist Club. Grace also told a humorous story of trying to dress a chicken for the first time. Roy tried to help, but he “didn’t know any more about it than I did.” It took two hours to dress the chicken, but Grace said it did taste good in the end.

Near the end of 1918 Grace was no longer working at the post office, and she was expecting her first child. That did not stop her, though, from helping to deliver holiday candy to 22 children in the town just before Christmas. With limited medical understanding at the time, Grace’s obituary said she caught a “heavy cold” from being outside in wintry weather, which developed into pneumonia, which caused her death on January 4, 1919. Shortly thereafter, it was decided Grace had died from the Spanish flu.

Grace’s obituary also reads that while she was working at the post office, “she made the acquaintance of the entire community, and her inviting disposition and obliging ways made every acquaintance a firm friend.” Her obituary further said that, while living in Carland, Grace had attended the Methodist Church, and after moving to Mason she had attended the Baptist Church. But Roy was an elder at the Presbyterian Church, so after marrying him she attended church there, and taught Sunday School in the primary room.

If Will Rose did die on January 4 in 1881 (rather than on January 2), it must have seemed extraordinary to Lottie that arguably the two worst days of her life had happened on January 4, first in 1881 and then in 1919.

What is the legacy of Grace Ramsdill Adams? She seems to have been a dedicated Christian, a good post office clerk, and respected by her community. I know she was well-beloved by her family. She named my mother “Gladys,” who carried that name for a lifetime of 78 years. Grace’s sister Nellie, in a second marriage, named a daughter “Grace,” as did my mother name her first daughter “Grace,” and now I have a granddaughter with the middle name of “Grace.” So Grace Adams had a niece and a great-niece named after her, and now has a great-great-great niece carrying her name.

Grace’s husband never remarried. He was a rural mail carrier for 15 years, an owner/manager of a movie theater for 20 years, a Justice of the Peace for 24 years, and an author of two novels. He was considered to be part of our extended family while I was growing up, and I remember him. In his old age Roy proposed marriage to the great-niece named after his wife, but that proposal was declined.

Alice French Andrews grew up in the Brethren in Christ Church in Michigan. She lives in Ada, MI.