Here’s a third excerpt — the last for now.

Last year, I had the privilege of participating in a colloquium on Pietism at Bethel University in Minnesota. (Thanks, Chris Gehrz!) My panel was asked to tackle the thorny question, “Does Pietism provide a usable past for today’s churches?” The proceedings from that panel should be published soon, in a forthcoming issue of The Covenant Quarterly. I’m looking forward to it!

I’ve recently expanded on some of my thoughts from that panel discussion in an article for the spring 2013 of In Part, the magazine for the Brethren in Christ community in the U.S. (It’s the second entry in their year-long “We Believe” series, which seeks to examine the four theological traditions that shape the contemporary Brethren in Christ in the U.S.: Anabaptism, Pietism, Wesleyanism, and Evangelicalism.) The article considers Pietism’s status as one of the founding streams in Brethren in Christ theology and its contemporary relevance to the Church. Here’s an excerpt:

Recently, a pastor friend and I had a conversation about how we introduce new people to the origins, beliefs, and practices of the Brethren in Christ (BIC) Church in the U.S. In addition to sharing about the Core Values and doctrinal statement that shape the BIC community, my pastor friend mentioned that he always describes its roots in various theological traditions. “I tell people we’re a Protestant denomination with a unique mix of Anabaptism, Wesleyan, and Evangelical doctrines,” he told me, adding, “I usually don’t mention Pietism. It just gets lost in the mix.”

What did my friend mean by this statement? Because he knows the defining role Pietism had in launching the BIC Church, I can only guess that he doubts the movement’s contemporary significance to our community life. Perhaps he meant that Pietism “gets lost” because of its negative connotations. Certainly the term “Pietist” (and related expressions like “piety” and “pious”) smacks of stuffiness and judgmentalism—hardly the basis for effective Christian ministry or vital Christian living.

Or perhaps he meant that Pietism “gets lost” because it has so little support among the BIC community today. As reported in a 2006 survey*, most BIC would describe their religious faith using terms like “Anabaptist” and “Evangelical.” A meager 1.3 percent would use the term “Pietist.” Clearly, very few among us today identify with this historic theological tradition.

Or perhaps my friend meant that Pietism “gets lost” because its major contribution to BIC theology—the notion of a heart-felt and life-changing conversion experience of the saving grace of God—is emphasized by other theological traditions in our heritage, like Wesleyanism and Evangelicalism.

No matter what my friend meant, it’s clear that this theological movement—so important in our community’s formation—no longer resonates in the way it once did. But can it? Is there more to Pietism than stodgy connotations and a redundant theology of salvation? How did the Pietist impulse first galvanize the BIC Church? And in what ways does our Pietist heritage position us for bold witness and effective ministry today?

You can probably guess my answers to some (if not all!) of those questions, but you’ll have to wait for the spring 2013 issue to read them in full!

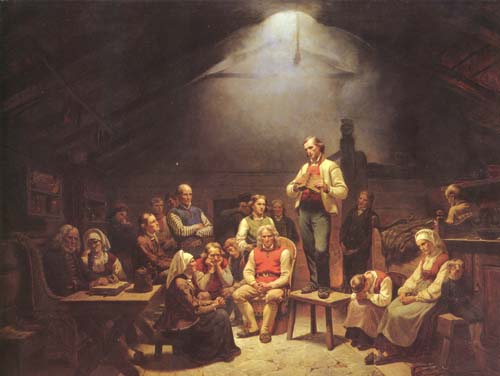

Thanks, Devin. I’m curious to learn the details of the illustration. Who, where, when etc?

Could “piety” be honoring the sacred mystery in life?

Hi Devin,

Thanks for your post. When your friend introduces the BICC as having a blend of Anabaptist, Wesleyan, and Evangelical elements — could we consider that referring to the Wesleyan element is a way of conveying the Pietist roots? I am thinking of Wesley’s crucial encounter with the Moravians as well as the mid-western expression of what might call “small-p” pietism in the Wesleyan-linked revival movements of the later 19thC.