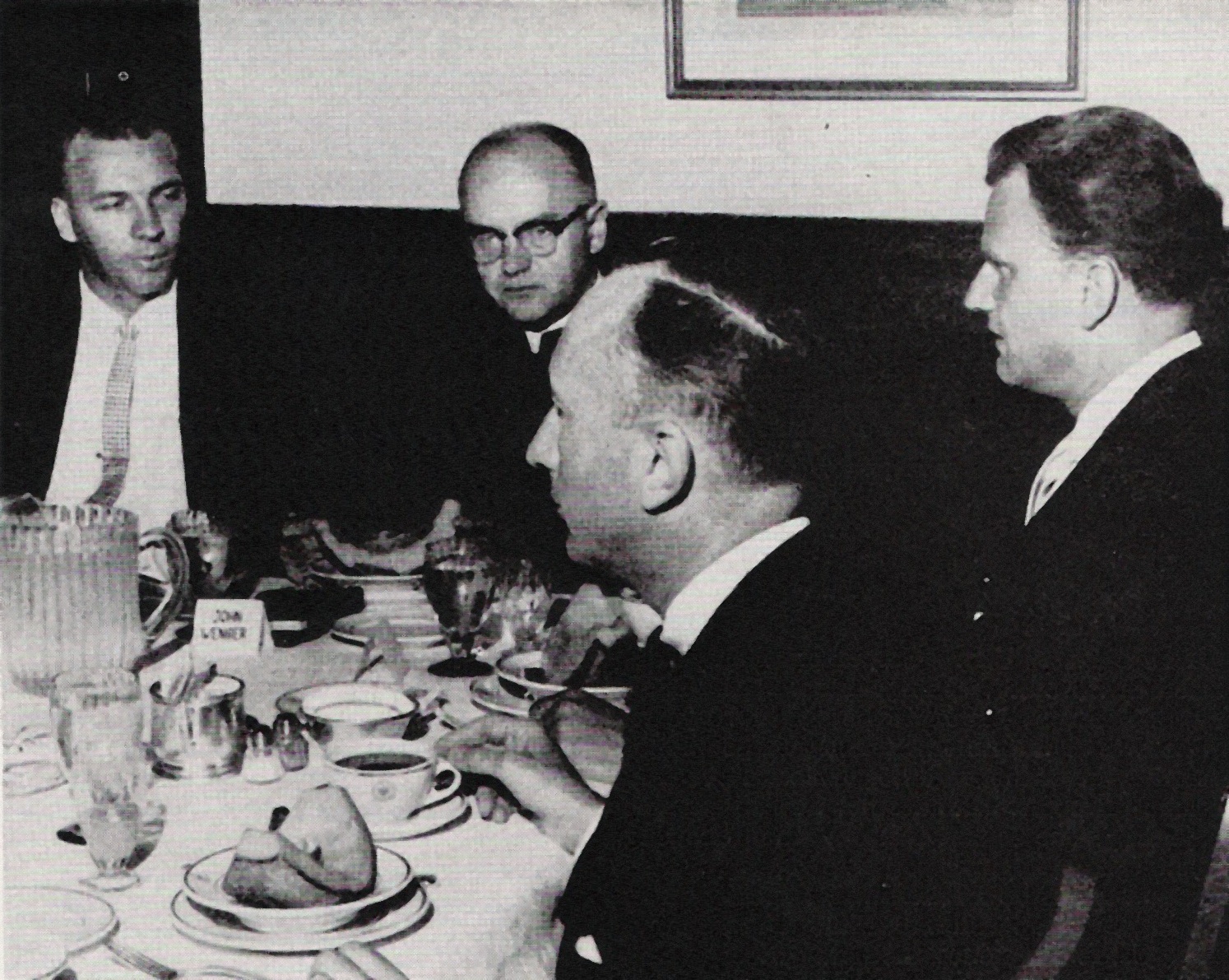

Today’s Photo Friday installment highlights a seminal event in Anabaptist history: a 1961 dialogue between Mennonite and Brethren in Christ leaders and Billy Graham — at the time, one of America’s most famous figures and undoubtedly the “face” of popular American Evangelicalism.

The dialogue happened on August 20, 1961, in Philadelphia. Those familiar with Mennonite history will recognize some of the denominational leaders who participated in the event, including John C. Wenger and Elmer Neufeld. Bishop, peace advocate, and Messiah College president C. N. Hostetter, Jr., represented the Brethren in Christ. As Hostetter’s biographer E. Morris Sider records:

Hostetter was consistently impressed with Graham. He heard Graham speak frequently at NAE [National Association of Evangelicals] conventions; he invariably labelled Graham’s sermons with such adjectives as “powerful” or “impressive.” [1]

No doubt others in the group had been similarly impressed by Graham’s style and presence — and no doubt they were aware of his celebrity among most of America’s Christians in the 1960s. Likely it was this combination of professionalism and popularity that led these Anabaptists into dialogue with “America’s preacher.” If they could convince Graham of the gospel message of peace, perhaps he could proclaim that message far beyond the bounds of American Anabaptism.

The October 21, 1961 issue of the Brethren in Christ publication, the Evangelical Visitor, gives further details on the conversation:

The purpose of the meeting was to engage in a personal conversation with Dr. Graham concerning the New Testament ethic of love and nonresistance and also to hear from Dr. Graham a word which might encourage and stimulate our churches to become more evangelistic. . . .

In response to the presentation, Dr. Graham replied that he appreciated deeply the privilege of listening to the testimony of other Christians. . . . He commented briefly on the problems involved in taking the nonresistant position, but noted the uncertainty and confusion among Christians regarding the proper attitude toward participation in war. He stated his personal openness and interest in meeting for more extended discussion on the doctrine of nonresistance. [2]

Interestingly, the event also crops up in a recent analysis of the “fragmentation of Evangelicalism” written by religion scholar Molly Worthen. In her post, Worthen argues that the mid-twentieth century popularity of Billy Graham among conservative Protestants projected a public image of Evangelicalism as unified across denominational lines and cooperative despite varying theological emphases. The reality, Worthen concludes, was much more complex. Numerous groups — Pentecostals, Southern Baptists, and Mennonites and Brethren in Christ among them — admired Graham for his popularity and conversionist message, but felt that aligning themselves with the so-called “Evangelical coalition” represented by the National Association of Evangelicals might compromise their denominational authority.

Worthen highlights the Graham dialogue as an example of this complex interplay between particular denominations and the larger Evangelical ecumenical movement:

After a detailed presentation of Anabaptist beliefs—particularly nonviolence—the Mennonites asked for Graham’s advice. How did evangelical leaders view Mennonites’ pacifism? How might they improve their evangelistic outreach?

Graham was gracious. This wasn’t the first time he had heard of Christian nonviolence; civil rights activists had been living and preaching it for years. Graham told the group that he “could easily be one of us in about 99% of what has been said,” the secretary recorded. He expressed willingness to discuss the doctrine of nonviolence in the future, but warned of the “historical danger of a denomination putting undue emphasis and overweighting ourselves on one particular point.”

Afterwards the Mennonites felt hopeful. Graham was “open to be led and to be taught,” and they planned to pursue more contact with evangelical leaders. Yet Graham was wary of appearing too easygoing in his theology. He insisted that no press release quote him directly.

In exchanges with neo-evangelicals, the Mennonites—like all good diplomats—continually revised their approach. They stressed common ground but grew more confident in their distinctive doctrines.

Years later, when a new generation of young evangelicals grew disillusioned with the Christian right and went looking for alternative models of discipleship, the Mennonites were ready. John Howard Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus—a closely argued defense of Christian nonviolence—enjoyed a long life beyond its 1972 publication. In 1976, ethicist Stephen Charles Mott called it “the most widely read political book in young evangelical circles in the United States.”

Interestingly, Worthen’s conclusions about Evangelical complexity echo my own observations about the ways in which the Brethren in Christ reacted to the rise of post-World War II Evangelicalism — the kind of Evangelicalism, at least, represented by Graham, the NAE, and other outfits like Christianity Today and Fuller Theological Seminary. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the Brethren in Christ really responded not just by joining the NAE — and thereby ratifying the claims of the post-war Evangelical movement — but also by resisting identification with this broad contingent of Protestants, and even, in some cases, seeking to reform these fellow Christians.

Interestingly, Worthen’s conclusions about Evangelical complexity echo my own observations about the ways in which the Brethren in Christ reacted to the rise of post-World War II Evangelicalism — the kind of Evangelicalism, at least, represented by Graham, the NAE, and other outfits like Christianity Today and Fuller Theological Seminary. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the Brethren in Christ really responded not just by joining the NAE — and thereby ratifying the claims of the post-war Evangelical movement — but also by resisting identification with this broad contingent of Protestants, and even, in some cases, seeking to reform these fellow Christians.

Certainly the Mennonites’ and Brethren in Christ’s attempt to “convert” Graham to a peace position reflects one effort to reform Evangelicalism.

NOTES:

[1] E. Morris Sider, Messenger of Grace: A Biography of C. N. Hostetter, Jr. (Nappanee, Ind.: Evangel Publishing House, 1982), p. 216.

[2] “Sixteen Church Leaders Meet with Billy Graham in Philadelphia,” Evangelical Visitor, October 21, 1961, p. 14.

2 responses to “Photo Friday: Billy Graham’s “99% Agreement” with Anabaptist Nonresistance”