Yesterday, I wrapped up the lecture portion of my course at Messiah College, HIST 391: Historical Study of Peace. Across the course of the semester, we’ve focused intently on American peace movements and tracked two different forms of peace activity within Christian circles: liberal Protestant pacifism (as represented by groups like the Fellowship of Reconciliation) and Anabaptist nonresistance, specifically as practiced by the Brethren in Christ. (We also devoted a single lecture to Catholic peacemaking, mostly in the form of the Catholic Worker movement led by Dorothy Day.)

Our final lecture was “Anabaptist Nonresistance after World War II.” I asked students to consider the evolution of Brethren in Christ nonresistance after World War II by comparing and contrasting two Brethren in Christ peace statements, one produced in the 1961 Articles of Faith and Doctrine and the other in the 1994 Articles of Faith and Doctrine. Among other things, the students noted the linguistic differences between the two statements: “nonresistance” disappears, replaced by emphases on “active peacemaking” and “justice.”

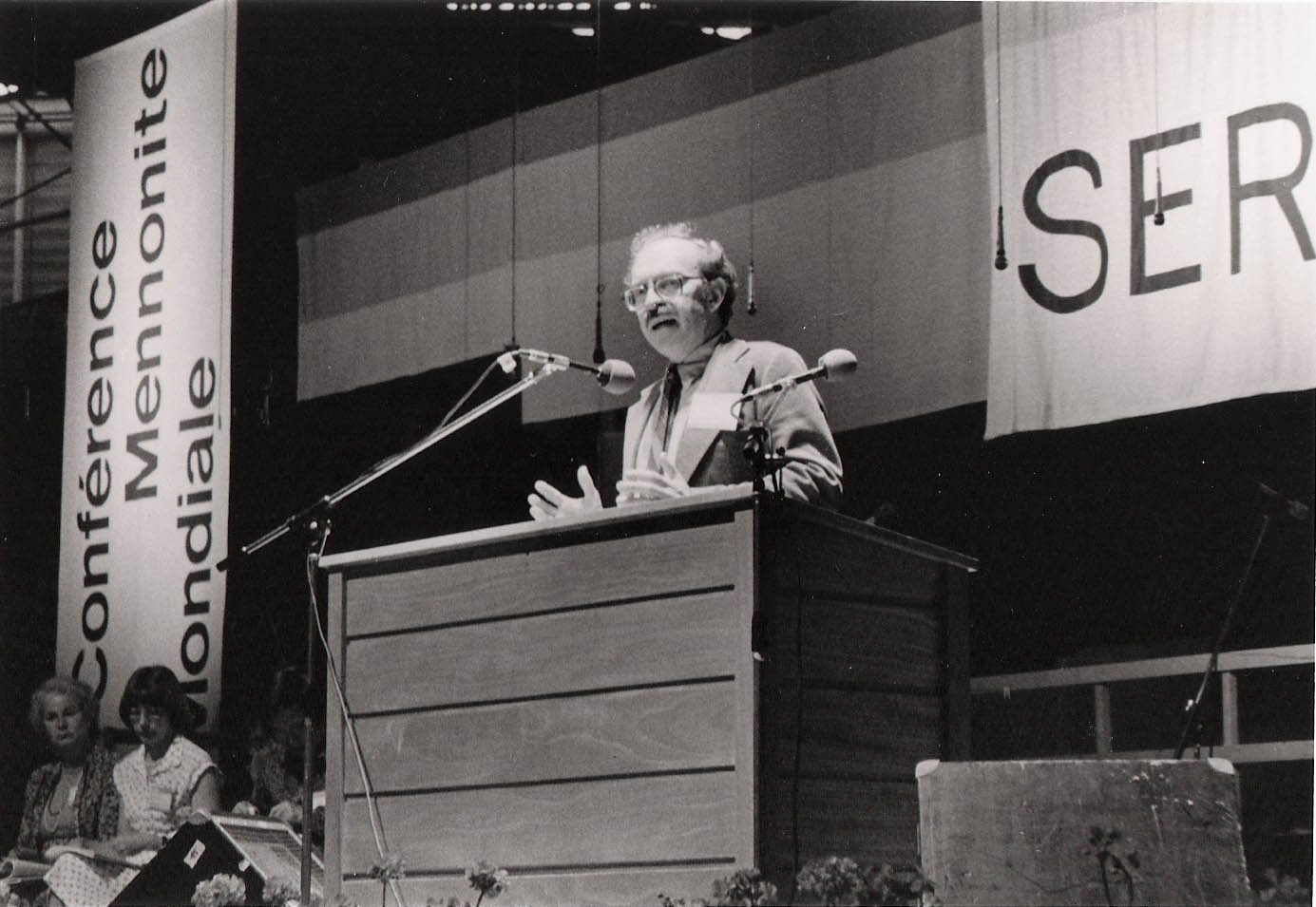

One story that I used to illustrate the shift was the story of Ronald J. Sider‘s influential sermon to the 1984 assembly of Mennonite World Conference in Strasburg, France — a story captured in today’s Photo Friday installment.

At the 1984 assembly, Sider — a Brethren in Christ theologian and educator, and author of the influential Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger (1977) — challenged his Anabaptist audience to consider new forms of peacemaking. His talk was driven by the historical currents swirling around him and his fellow Global North Anabaptists: by the early 1980s, “low-intensity” wars, rising rates of global terrorism, and other politicized uses of violence and oppression. For the last three decades, radicals and other leftists in America and around the world had increasingly turned to the techniques of Gandhian nonviolence to address injustices and stimulate positive, peaceful change. Mennonites and Brethren in Christ alike were looking for new ways to express their peace convictions.

In his speech, Sider urged Brethren in Christ, Mennonites, and other Historic Peace Churches to take the lead in searching for new approaches to proactive peacemaking. He criticized the politicization of Anabaptist groups, especially those who claim to oppose violence but endorse the arms race and military preparedness at the ballot box. He declared:

If we want wars to be fought, then we ought to have the moral integrity to fight them ourselves. To vote for other people’s sons and daughters to march off to death while ours safely register as conscientious objectors is the worst form of confused hypocrisy. . . . Everyone assumes that for the sake of peace it is moral and just for soldiers to get killed by the hundreds of thousands, even millions. Do we not have as much courage and faith as soldiers?

Seeking alternative solutions, Sider charged Anabaptists and other Christians who care about peacemaking to put themselves in the midst of violent situations. As one writer reported in the Brethren in Christ’s Evangelical Visitor newspaper:

[Sider] suggested that a praying and caring peacekeeping force of 100,000 Christians be trained and ready to stand between warring parties in such places as Central America, Northern Ireland and Southern Africa.

Sider concluded:

Over the past 450 years of martyrdom, immigration and missionary proclamation, the God of shalom has been preparing us Anabaptists for a late twentieth-century rendezvous with history. The next twenty years will be the most dangerous—and perhaps the most vicious and violent—in human history. If we are ready to embrace the cross, God’s reconciling people will profoundly impact the course of world history . . . This could be our finest hour. Never has the world needed our message more. Never has it been more open. Now is the time to risk everything for our belief that Jesus is the way to peace. If we still believe it, now is the time to live what we have spoken.

(You can read Sider’s speech in its entirety here.)

The result of Sider’s speech was the formation of Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT), an organization that sends trained nonviolent peacemakers into situations of conflict to aid in resolution and reconciliation. Here’s how the organization describes itself on its website: “We believe we can transform war and occupation, our own lives, and the wider Christian world through the nonviolent power of God’s truth, partnership with local peacemakers, and bold action.”

Though the organization developed out of a Brethren in Christ theologian’s speech, its initial sponsors were Mennonites, Church of the Brethren, and Quakers. Today, it positions itself as an ecumenical body.

What does any of this have to do with the semantic shift in Brethren in Christ language about its peace position?

Sider’s speech argues that Christian peace activity should be active, not passive. It should focus on what we do, not on what we don’t do. It called for a kind of nonviolent army, a group of peacemakers who would be willing to risk their lives in order to bring God’s peace and justice to situations of violence and oppression. He also invoked language like “justice” — terms that would have been foreign to the nonresistant Brethren in Christ (and Mennonites) of an earlier generation.

Sider wanted to see groups like the Brethren in Christ do more than refuse to participate in war (i.e., nonresistance). He wanted them to engage in active peacemaking. To use classic Anabaptist language, Sider was saying that it’s one thing to “refuse to take up the sword.” But it’s entirely another thing — and perhaps a more Christian thing — to imagine and practice “an alternative to the sword.”